There is more to the job of a Hurricane Hunter than meets the eye. Researchers, pilots, and crew from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) bravely fly into one of the most dangerous environments on Earth to collect data inside a tropical cyclone, which helps to improve forecast models and protect lives and property.

Aviators with NOAA’s Commissioned Officer Corps headquartered at NOAA’s Aircraft Operation Center pilot three Hurricane Hunter aircraft (two Lockheed WP-3D Orion turboprop aircraft and one Gulfstream IV-SP jet) to support researchers from NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML), Environmental Modeling Center (EMC), and National Hurricane Center (NHC).

Have you ever wondered what an average day looks like for a NOAA Hurricane Hunter? Follow along as Holly Stahl, a communications intern with AOML through the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS) traveled to Aruba in September 2022 to join a Hurricane Hunter mission into Hurricane Fiona.

Photo Credit: AOML/NOAA

A typical research mission can take roughly 8 – 10 hours to complete. Here’s what the hurricane research team’s day looked like for a 4:00 AM planned flight:

Meet the science team in the hotel lobby

1:30 AM

Shuttle to Queen Beatrix International Airport in Oranjestad, Aruba

1:45 -2:00 AM

Pre-Flight Mission Brief

-

The flight director conducts a mission brief with the science team to review the planned route, mission profile, data collection objectives, current and forecasted storm development, expected hazards, and weather for takeoff.

2:15-3:00 AM

-

Board the NOAA P-3 Hurricane Hunter aircraft, nicknamed ``Kermit`` after the Sesame Street frog

3:15 AM

Planeside Briefing

- Flight crew goes over safety procedures, in-flight responsibilities are assigned to crew members, and any updates or changes to the mission plan are communicated.

3:30-4:00 AM

Ferry Flight to the Storm's Edge

4:00-5:30 AM

Flying Through Hurricane Fiona

5:30 -10:30 AM

Ferry Flight Back to Aruba

10:30 AM-12:00 PM

Post-Flight Briefing

- Discuss any in-flight issues and if all science goals were accomplished.

12:00-12:30 PM

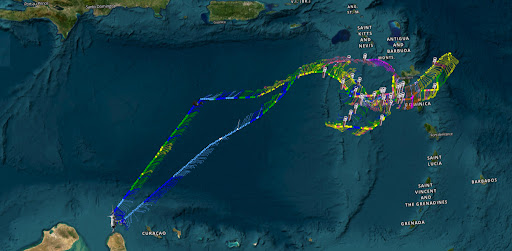

Photo Credit: Tropical Atlantic - Interactive webpage

Holly spoke with a few of the AOML scientists involved with the missions into Hurricane Fiona to learn more about their responsibilities and what it’s like to be a part of the NOAA Hurricane Hunter team. Below are the interviews with the scientists.

Jason Dunion

Photo Credit: NOAA/AOML

Jason Dunion, Ph.D., is a meteorologist with AOML’s Hurricane Research Division through the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS). He is also the director of the 2022 and 2023 Hurricane Field Program, which supports NOAA’s Advancing the Prediction of Hurricanes Experiment (APHEX). APHEX was developed in partnership with NOAA’s Environmental Modeling Center, National Hurricane Center, Aircraft Operations Center, and AOML’s Physical Oceanography Division to improve the understanding and prediction of hurricane track, intensity, structure, and associated hazards.

Interview with Jason Dunion

What was your role on the September 17 flight into Hurricane Fiona?

I was a ground-based project scientist for this flight into Hurricane Fiona. I helped design the flight patterns to best sample the storm and coordinated the operational missions every 12 hours to ensure they were successfully executed. I also coordinated with the National Hurricane Center to get up-to-date Tail Doppler Radar (TDR) data into their forecast models for analysis. I also confirmed that dropsonde data collected onboard the aircraft were being transferred in real-time to the Global Telecommunication System for inclusion in weather modeling efforts around the world.

What are your responsibilities on the ground during a research mission and how do you support the science being conducted?

Before the research can begin, I help design the optimal flight plan to collect the best data possible and make sure that the scientific instruments on the aircraft are available to support that day’s mission.

During a mission, I’m in constant communication with the scientists onboard to strategize and make adjustments to the flight pattern in real-time. I also coordinate with other agencies such as NASA and the Office of Naval Research who assist with the research being conducted. I am always looking ahead, analyzing the logistics of crewing each mission and planning to bring in new scientists for any necessary crew repositioning.

What are the most common setbacks/challenges observed during a research flight?

Aircraft maintenance can be a challenge in the field as it can be harder to get replacement parts when deployed away from our home hangar. We don’t want to miss any opportunities for research or have any critical gaps in the data, so we must decide how to adjust given the limitations of the aircraft.

Deciding on the initial positioning of the aircraft can also be a challenge. We want to be located in a place where the tropical cyclone impacts are low, but also don’t want an extremely long ferry flight out to the storm’s location.

What are your responsibilities as the director of the Hurricane Field Program?

As director of the Hurricane Field Program, I have responsibilities throughout the year. In the winter, I lead two science debriefing sessions, in which the research team looks back at the previous hurricane season to discuss the data that was collected and what advancements should be made for the upcoming season. I participate in a postseason Hotwash event, in which all the agencies involved in hurricane research get together and discuss what was done well that hurricane season, and what can be done better for the upcoming season. I also present APHEX overviews and future plans at various conferences and workshops across the country.

Throughout the spring, I work with the Hurricane Research Division at AOML and other collaborators (such as NOAA’s Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing (GOMO) program, the Office of Naval Research, or the Scripps Institution of Oceanography) to develop the next season’s Field Program plan. We discuss ideas about future research experiments to be conducted and what instrumentation would be required for these experiments.

As the Atlantic hurricane season approaches, I ensure that all crew members have completed their required water survival and scientific crewing training, as well as all necessary paperwork to be cleared to fly. Once hurricane season begins on June 1, my fellow scientists and I stay ready and alert to fly into whatever interesting storms Mother Nature throws our way.

“Our field program has an extremely important partnership with the University of Miami, as almost half of our contributing scientists are affiliated with CIMAS.”

– Jason Dunion, Ph.D., CIMAS affiliate and director of the 2022 and 2023 Hurricane Field Program

What is your favorite part about being a Hurricane Hunter?

The most interesting part of the job for me is trying to figure out what makes hurricanes tick. We’re really explorers trying to better understand the different puzzle pieces of how storms track, intensify, and change their structure, and that always keeps me coming back for more.

Rob Rogers

Photo Credit: NOAA/AOML

Rob Rogers, Ph.D., is a meteorologist and research scientist who has been working with AOML’s Hurricane Research Division since 1998. His primary work includes investigating tropical cyclone intensity change and structure using aircraft observations and numerical models. Rob was recently selected to be the science director for the 2023 Hurricane Field Program. He is also the leader of AOML’s Observations team, which is responsible for providing status updates on aircraft observations and how they can use those observations to further tropical cyclone research. His team seeks out collaborations within the academic community or with operational partners and works to improve forecasts through better situational awareness for the National Hurricane Center.

Interview with Rob Rogers

What was your role on the September 17 flight into Hurricane Fiona?

On this flight into Hurricane Fiona, I was the onboard radar scientist, responsible for monitoring the status of the radar system, providing input to the scientists on the ground, and troubleshooting or providing quality control when necessary.

What are your responsibilities in the air during a research mission and how do you support the science being conducted?

During the mission, my main responsibility was to watch the radar to make sure that the antennas were rotating properly and collecting good data. If any issues were to arise, I would work with the flight crew to reboot the radar system and communicate these issues with the ground-based radar scientist.

I also reviewed the real-time analyses from the radar within 15 minutes of completing a pass through the storm’s center to gather information on the inner core structure of the storm. Is the storm getting better organized and intensifying, or is it falling apart? I assessed what the storm looked like throughout the course of the mission.

What are the most common setbacks/challenges observed during a research flight?

There are occasional issues with the execution of the mission itself, whether that be instrumentation problems or issues with communications, as satellite communications are not always reliable, especially in certain parts of the ocean basin.

Weather may also not cooperate with the mission plans. There may be areas of extreme turbulence or deep convection that the flight crews don’t want to go through. In this case, I would work with the mission’s lead project scientist to adjust the flight plan and maximize the chances of collecting the high quality data we desire.

Fatigue can also be an issue, as I flew research missions for almost the entire month of September!

What are your responsibilities as the science director of the Hurricane Field Program?

As science director for the Hurricane Field Program, it is my duty to solicit input and research ideas from AOML’s Hurricane Research Division. My goal is to ensure that everyone gets the chance to get their research done using the aircraft provided by NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center (AOC). Once experiments are proposed, they are presented to AOC to show what flight patterns would be required in order to conduct specific research experiments. I want to make sure that the science we aim to do can be accomplished safely!

What are your main responsibilities during the off season?

As leader of the Observations team, I conduct monthly team meetings to discuss status updates, future plans, and current research being conducted. Our team works to process, quality control, and reprocess data collected from the previous hurricane season, then analyze these data for future research projects to better understand the physical processes related to tropical cyclone structure and intensity change. I also attend countless meetings and workshops throughout the off season, in addition to writing papers.

What is your favorite thing about being a Hurricane Hunter?

When I tell people about what I do, the first question they ask is, “Are you scared?” My answer – usually not, as I have confidence in the aircraft, the flight crew, and the equipment. However, I have experienced a few hair-raising incidents, such as encountering severe turbulence or the plane being struck by lightning. I wasn’t really concerned until a flight into Hurricane Ian last season. It was a very unusual flight with unexpected turbulence that I had never encountered before, and I wasn’t sure how the plane was going to react and respond to the sudden changing of the winds.

“I enjoy that every flight is different. Over the years, our focus has changed from how a hurricane responds to vertical shear, to rapid intensification, to vortex alignment. I enjoy the discovery of seeing something that verifies or refutes our hypothesis.” – Rob Rogers, Ph.D., science director of the 2023 Hurricane Field Program

George (Trey) Alvey

Photo Credit: Holly Stahl/AOML/NOAA

George (Trey) Alvey, Ph.D., is an associate scientist with the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS) in collaboration with AOML’s Hurricane Research Division. Trey is a member of the Hurricane Field Program whose research focuses on early-stage tropical cyclones that are very disorganized and complicated from both a forecast and a flying perspective. He conducts some observational research dealing with the data collected from the instruments on the aircraft, as well as some modeling work. Trey applies the observations and uses models to get at finer scale details that can’t be measured in person.

Interview with George (Trey) Alvey

What was your role on the September 17 flight into Hurricane Fiona?

On this flight, I was the lead project scientist, charged with overseeing the mission and ensuring that the scientific goals of the missions were completed. I communicated directly with the flight director and the ground-based science crew to target specific regions of the storm. I was also responsible for calling out exactly when the GPS dropwindsondes should be released. My goal was to gather data from most quadrants of the storm to get the best coverage possible.

“This was a challenging flight, as we had to adapt the flight pattern several times on the fly. The storm’s center had a repositioning or reformation and had shifted from the previous location that we had expected it to be.”

– George (Trey) Alvey, Ph.D., AOML lead project scientist on the September 17 mission into Hurricane Fiona.

What are the most common setbacks/challenges observed during a research flight?

Dealing with and adapting to a storm that is changing rapidly can be a challenge. Precipitation fields or areas of deep convection are always evolving, especially in weaker storms. Flight patterns need to be adjusted on the fly in these situations.

Flying over land can also be a challenge as there are airspace restrictions that need to be strictly followed.

Making sure that you are on the same page with the flight director is extremely important, as they have the final say on if something is safe to do. They communicate directly with the pilots, allowing for a more concise chain of information.

“The Aircraft Operations Center does a ton of work to make sure the planes are good to go, as they get beat up by flying through these conditions consistently. Kudos to the pilots and the flight crew, who are the ones doing the hard work. Without the crew, there is no way we would get the data to make this research possible. It takes a lot of effort and behind the scenes work for an individual flight.”

– George (Trey) Alvey, Ph.D., AOML lead project scientist on the September 17 mission into Hurricane Fiona.

What are your main responsibilities during the off season?

During the off season, I spend most of my time working on research related to observations and analyzing previous model runs. I think of new research ideas for the upcoming hurricane season, develop new research modules based on previous experiences, and improve modules already in place.

Kathryn Sellwood

Photo Credit: Holly Stahl/AOML/NOAA

Kathryn Sellwood is research associate with AOML’s Hurricane Research Division through the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS). She is in charge of the hurricane dropsonde archive and works with AOML’s Data Assimilation group to look at ways of improving the use of the observations taken using aircraft to improve hurricane models.

Interview with Kathryn Sellwood

What was your role on the September 17 flight into Hurricane Fiona?

I was the dropwindsonde scientist on this flight into Hurricane Fiona. My job was to keep track of where the GPS dropsondes were released with relation to the storm center (on the end of a leg, the middle of a leg, the center, or the eyewall). Once the instrument splashes into the ocean, I run the data collected through a quality control software, called Aspen and make additional corrections when needed. I also ensure that the data collected is high quality and gets off the aircraft in a timely manner into the Global Telecommunication System for anyone who wants to use it.

What are the most common setbacks/challenges observed during a research flight?

Motion sickness! It has gotten better over the years, but it’s something I still struggle with on occasion.

What are your main responsibilities during the off season?

During the off season, I collect, organize, and quality control all of the dropsonde data collected from the aircraft, then upload it to AOML’s website. I also test new ways to use more of the data collected, including the data from the Area-I Altius 600 small uncrewed aerial system (sUAS) that was deployed into the eye of Hurricane Ian in September 2022.

What is your favorite thing about being a Hurricane Hunter?

“It’s always exciting because you don’t know what’s going to happen. Especially if it’s not a hurricane yet and it seems like a disorganized tropical storm, it may become more organized while you’re in the air.”

– Kathryn Sellwood, AOML dropwindsonde scientist on the September 17 mission into Hurricane Fiona.

Hurricane hunters take a literal look into the eye of the storm in order to help forecasters make accurate predictions during a hurricane, and help hurricane researchers achieve a better understanding of tropical cyclone processes, improving their forecast models. Their courage helps further science and save lives.

Photo Credit: NOAA/AOML