The latest episode of the educational television series “Waterways” features coral research conducted by NOAA scientists in the Florida Keys. As the global ocean becomes more acidic, NOAA is documenting these changes and their impact on organisms like corals. The first part of the episode entitled “Ocean Acidification & Tortugas Tide Gauge” features AOML researchers discussing how they study this process and the high tech tools they use to monitor and describe changes in coral growth due to a more acidic ocean.

The ocean is becoming more acidic, but what does that really mean? On a pH scale of 1 – 14, 1.0 is strongly acidic and 14.0 is strongly alkaline or basic; typically ocean waters are slightly alkaline and fall around 8.0-8.1 on this scale. Over the past hundred years, the pH of seawater has decreased, dropping 0.1 pH units. This is due to ocean acidification, a process that occurs when seawater absorbs carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air. The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has steadily increased since the late 1800s. As more carbon dioxide is added to the air, the amount absorbed into the oceans increases, further decreasing pH. NOAA scientists monitor these changes and their possible effects.

Some of the organisms affected by ocean acidification are corals and shellfish, animals that build their skeletons or exoskeletons underwater. Stony corals secrete skeletons made of calcium carbonate, or limestone, and build coral reefs. These reef ecosystems are valuable resources to many organisms, which rely on the corals for shelter and food. As the corals build their skeletons, organisms, such as fish and sponges, simultaneously eat away at the calcium carbonate. This back and forth process of growth and erosion is a natural phenomenon in the coral reef ecosystem.

As seawater’s pH decreases, it becomes more difficult for corals to efficiently produce limestone. The trend of ocean acidification may result in coral reefs eroding faster than they are being built. Scientists must measure the net growth, how fast a coral is growing, subtracted by how fast it is eroding, in order to determine the negative impacts of ocean acidification on corals. Using this formula, NOAA scientists discovered coral reefs in the Florida Keys are in an erosive state, losing grams of calcium carbonate per year. One third of reefs in the wider Caribbean are eroding faster than they are growing, which could be detrimental to ocean and reef health. Twenty five percent of ocean animals rely on coral reefs to survive and many reef-associated organisms are important sources of protein for human populations along tropical coastlines.

With support from NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation and Ocean AcidificationPrograms, AOML scientists established a long-term monitoring site to learn more about the effects of ocean acidification. At Cheeca Rocks, in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, there is a Moored Autonomous pCO2 (MAPCO2) buoy constantly collecting data on carbon dioxide in the air and water, seawater pH, and temperature, providing NOAA scientists the opportunity to observe changes in the environment. These data are reported in near-real-time on the internet via satellite relay.

| The bands on this piece of coral represent a decade worth of coral growth. Credit: NOAA/AOML |

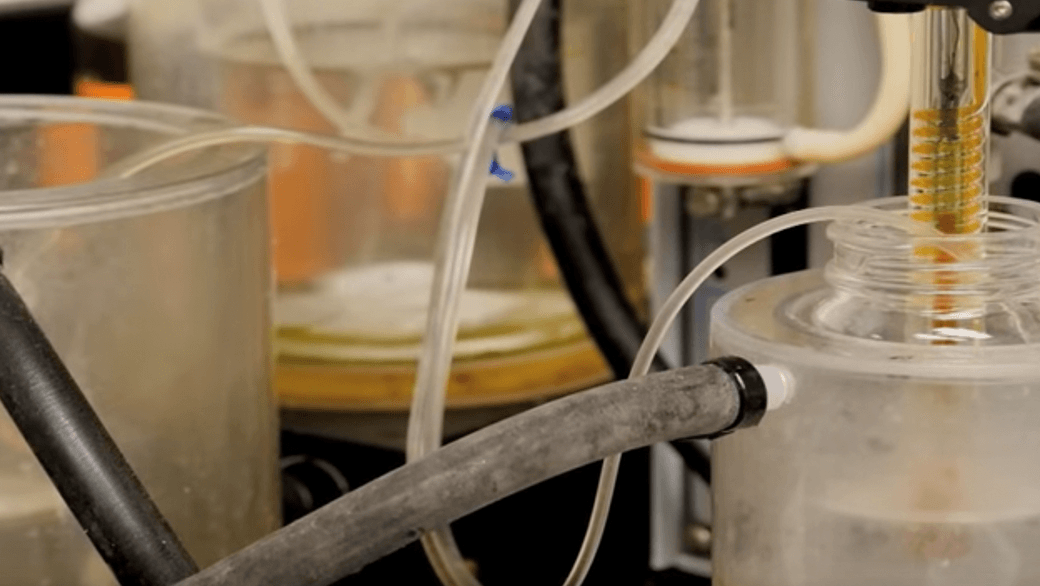

Scientists can measure changes in a coral’s growth and density to determine how it is affected by acidification. Corals, like trees, have an annual banding pattern, which is used to determine annual growth rates. Scientific divers take core samples from larger corals, and examine their density bands with a micro-CT scanner. The scanner produces three-dimensional X-ray images that allow scientists to study the how much skeletons grow each year. A different three-dimensional scanner accurately measures the surface area and volume of living corals, whose architecturally complex exterior make it very challenging to measure.

With these long term monitoring sites and innovative technologies, scientists can provide information and analysis that helps resource managers and political leaders make laws and decisions for the future. This research may help discover methods to reduce the impacts from ocean acidification and mitigate the current damage to coral reefs.

With almost 300 episodes produced since 1993, the “Waterways” series is a joint project between Everglades National Park, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Waterways inform viewers of the diverse wonders of the south Florida ecosystem, and the research and conservation programs that protect them. “Waterways” airs on public and government channels throughout the state of Florida — check local listings for scheduling. Episodes can be viewed on the WaterwaysTvShow YouTube channel.

The NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program supports effective management and sound science to preserve, sustain and restore valuable coral reef ecosystems for future generations. The program works in strong partnership with coral reef managers to protect coral reefs by addressing national threats, including impacts from fishing, pollution and climate change, and implementing local conservation activities.

The Ocean Acidification Program (OAP) provides leadership to understand and predict changes in the Earth’s environment as a consequence of continued acidification of the oceans and Great Lakes, and conserve and manage marine organisms and ecosystems in response to such changes. In order to do this the OAP fosters and maintains relationships with scientists, resource managers, stakeholders, policy makers, and the public in order to effectively research and monitor the effects of changing ocean chemistry on economically and ecologically important ecosystems and species.

Coral colonies at Cheeca Rocks, showing evidence of coral bleaching. Photo Credit: NOAA/AOML

Buoy that measures carbon dioxide at Cheeca Rocks in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Photo Credit: NOAA/AOML

3-D scanner to measure coral surfaces. Photo Credit: NOAA/AOML