New findings also point to coastal construction as potential way of further spreading coral disease

Originally published by the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute of Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS)

MIAMI—A new study found that seafloor sediments have the potential to transmit a deadly pathogen to local corals and hypothesizes that sediments have played a role in the persistence of a devastating coral disease outbreak throughout Florida and the Caribbean.

These new findings from the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science-led research team could help mitigate the spread of the deadly disease— stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD)—that causes white lesions and rapid tissue loss to reef-building corals.

Since first appearing in waters off Miami in 2014, stony coral tissue loss disease has now spread throughout all of Florida’s coral reefs as well as the wider Caribbean, affecting over 20 coral species and killing millions of coral colonies. To date, the microbe or suite of microbes causing the disease have not been identified, making it very difficult to manage and treat.

“Our findings indicate that disease-associated microbes may reside in sediments, which can help explain how this disease outbreak has been able to spread and persist largely unabated for the last seven years,” said the study’s lead author Michael Studivan, an assistant scientist with UM’s Cooperative Institute of Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS) based at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Lab (AOML).

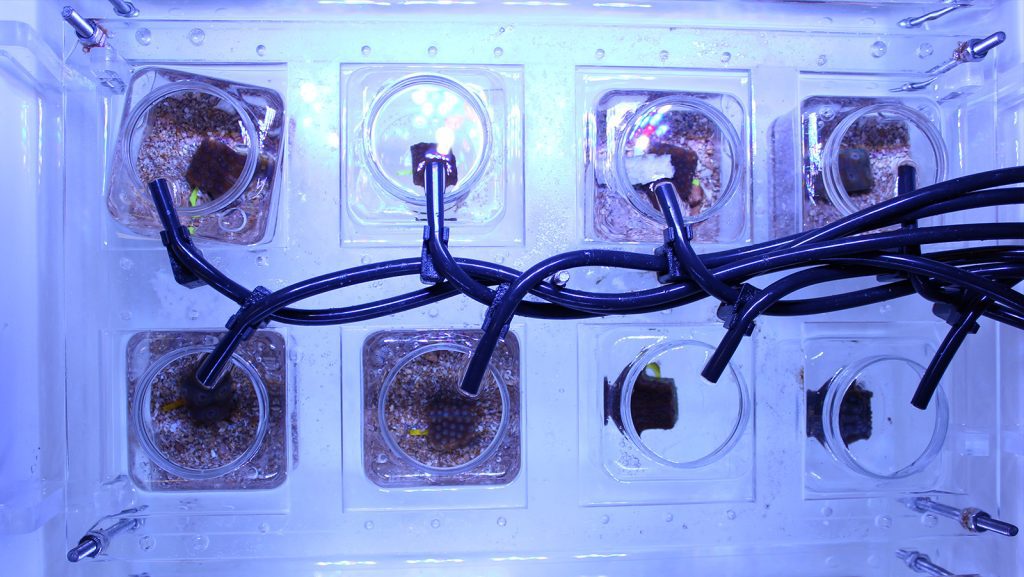

To study the spread of the disease, the scientists built a disease transmission apparatus in the CIMAS Experimental Reef Lab to test and identify possible disease vectors and sources. They inoculated reef sediments with SCTLD from diseased corals and exposed these sediments to healthy corals. For four weeks, they monitored the corals daily for signs of the disease’s characteristic white lesions to determine how many individuals were infected, and how quickly the disease progressed.

The researchers found that disease-inoculated sediments were able to transmit SCTLD pathogens, resulting in visible signs of the disease in as little as 24 hours.

In addition, the scientists compared DNA extracted from sediments exposed to SCTLD to those that were not exposed to disease to identify several known pathogens that are found on reef environments near diseased corals, including the group of bacteria Vibrio spp., suggesting that some SCTLD-associated microbes can be found in sediments.

“We hope this new information will provide managers with critical information needed to respond to the SCTLD outbreak, especially in the context of mitigating further disease spread with coastal construction activities like dredging and beach renourishment,” said study coauthor Ian Enochs, a research ecologist and head of AOML’s Coral Program.

The study, titled “Reef Sediments Can Act as a Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease Vector,” was published in the Jan. 13 issue of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science. The project was funded by NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program (grant #31252) and NOAA OAR ‘Omics Program.