The Experimental Reef Lab

A tool for simulating dynamic future conditions on contemporary reef organisms

SCROLL TO LEARN MORE

Who We Are

Read More News

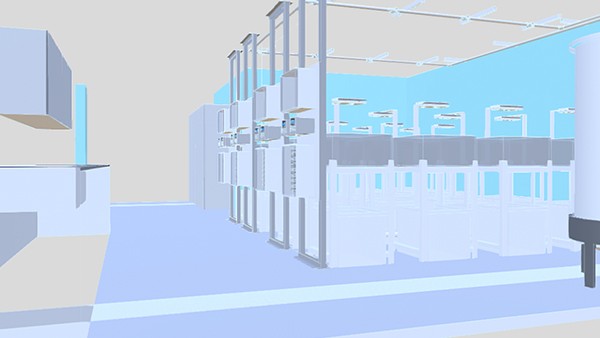

Virtual Tour

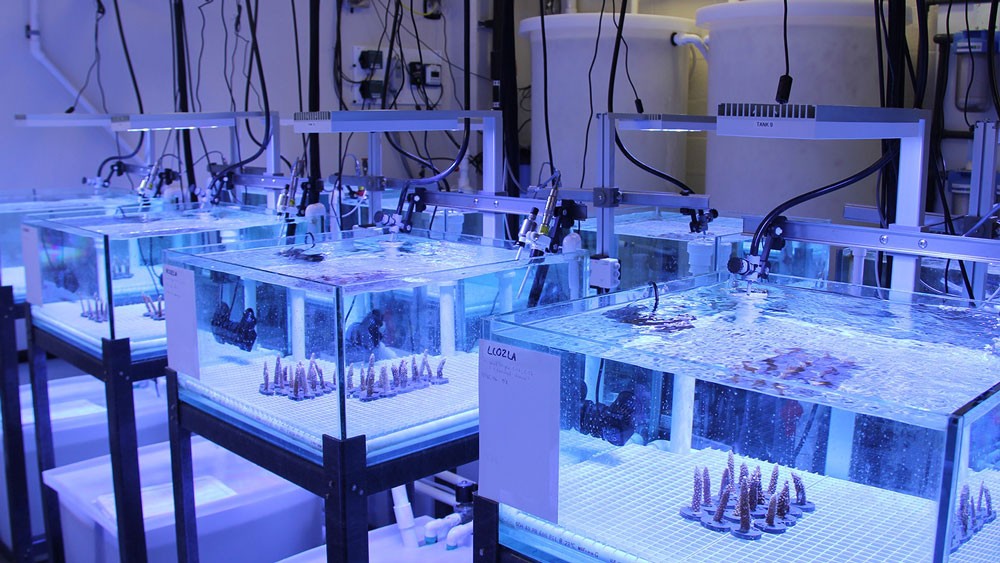

Automated Logging and Control System

One of the unique features of the lab is the fully automated logging and control system, facilitating real-time manipulation of dynamic levels for temperature, pH, and/or light treatments. Scientists have used the Experimental Reef Lab’s system to study how certain genotypes of corals may be more resilient to temperature stress, how daily pH fluctuations enhance coral growth, and how ocean acidification will lead to accelerated reef erosion.

Driving Innovative Science

With Experimental Design

AOML’s Ocean Chemistry and Ecosystems Division has taken a visionary approach to answering our most pressing questions about coral reef health by stepping outside of science and embracing new technology to engineer in-house solutions. This lab was built with in-house materials and technology from the Advanced Manufacturing and Design Lab. Visit the lab page.

We are leading stewards of a cleaner, healthier, more sustainable ocean.

We are using state of the art techniques for measuring coral growth and calcification. This video shows how we can assemble hundreds of x-ray images into a 3D model of endangered staghorn coral. This type of analysis allows us to look at skeletal density, structure, and coral growth in very high detail. These aspects of the coral will be influenced by ocean acidification and are important characteristics to consider when establishing management and restoration strategies.

Featured Publication

Marked annual coral bleaching resilience of an inshore patch reef in the Florida Keys: A nugget of hope, aberrance, or last man standing?

Annual coral bleaching events, which are predicted to occur as early as the next decade in the Florida Keys, are expected to cause catastrophic coral mortality. Despite this, there is little field data on how Caribbean coral communities respond to annual thermal stress events. At Cheeca Rocks, an inshore patch reef near Islamorada, FL, the condition of 4234 coral colonies was followed over 2 yr of subsequent bleaching in 2014 and 2015, the two hottest summers on record for the Florida Keys. In 2014, this site experienced 7.7 degree heating weeks (DHW) and as a result 38.0% of corals bleached and an additional 36.6% were pale or partially bleached. In situ temperatures in summer of 2015 were even warmer, with the site experiencing 9.5 DHW. Despite the increased thermal stress in 2015, only 12.1% of corals were bleached in 2015, which was 3.1 times less than 2014.

Partial mortality dropped from 17.6% of surveyed corals to 4.3% between 2014 and 2015, and total colony mortality declined from 3.4 to 1.9% between years. Total colony mortality was low over both years of coral bleaching with 94.7% of colonies surviving from 2014 to 2016. The reduction in bleaching severity and coral mortality associated with a second stronger thermal anomaly provides evidence that the response of Caribbean coral communities to annual bleaching is not strictly temperature dose dependent and that acclimatization responses may be possible even with short recovery periods. Whether the results from Cheeca Rocks represent an aberration or a true resilience potential is the subject of ongoing research.

Bleached Reef (Oct 9)

Bleached Reef (Oct 9) Recovered Reef (Nov 6)

Recovered Reef (Nov 6)Gintert, B. E., Manzello, D. P., Enochs, I. C., Kolodziej, G., Carlton, R., Gleason, A. C., & Gracias, N. (2018). Marked annual coral bleaching resilience of an inshore patch reef in the Florida Keys: A nugget of hope, aberrance, or last man standing?. Coral Reefs, 1-15.