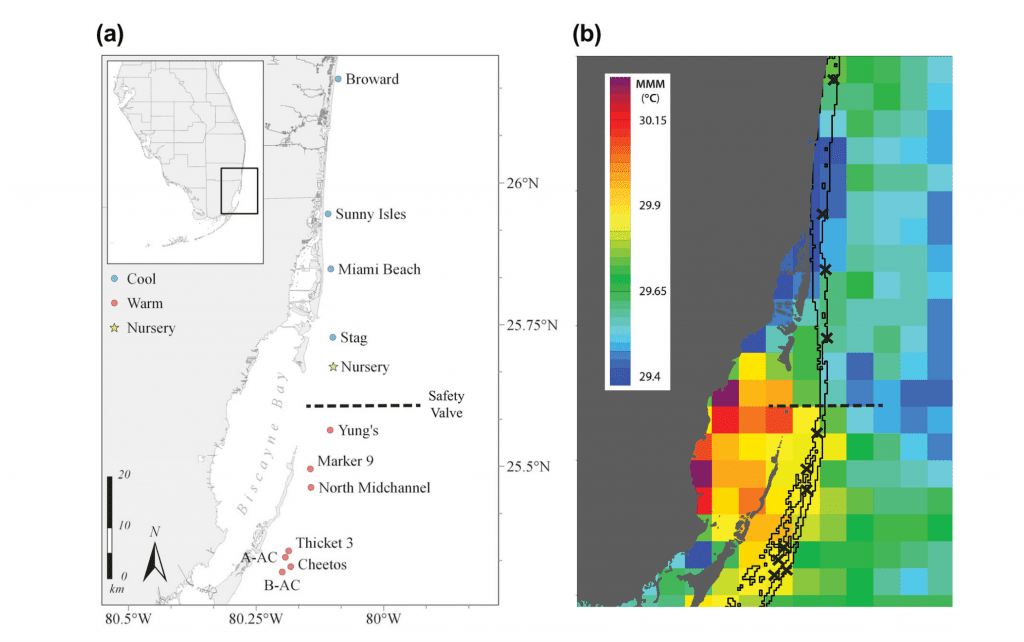

A new study by researchers at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory suggests that outplanting corals, specifically staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) from higher temperature waters to cooler waters, may be a better strategy to help corals recover from certain stressors. The researchers found that corals from reefs with higher average water temperatures showed greater healing than corals from cooler waters when exposed to heat stress.

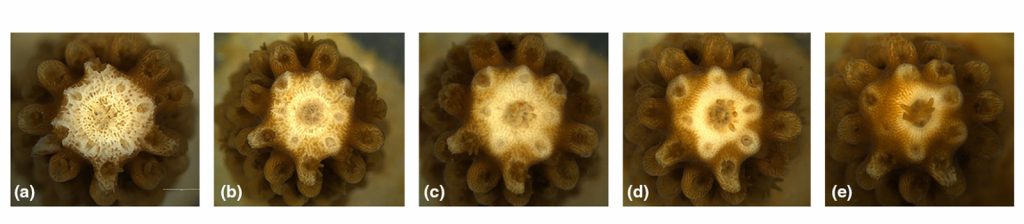

Researchers collected corals of 18 genotypes from UM’s coral nursery that were originally sourced from different reefs along Florida’s coast and monitored them for recovery after exposure to heat stress. They found that corals that were exposed to increased water temperatures did not heal as successfully as those corals that were kept at a constant temperature, but that being from a warmer donor reef increased the likelihood of healing for those exposed to increased temperatures. The results from this study suggest that sourcing corals from warmer reefs and outplanting them into cooler environments that may be likely to experience temperature increases in the future would increase their chances of recovery under heat stress. By identifying these genotypes that are more resilient to certain stressors, restoration specialists will be able to incorporate this knowledge into their practices and increase the likelihood of recovery and survival for corals during outplanting.

“We now have additional evidence that coral colonies can maintain certain characteristics and attributes even after they are relocated to a nursery. This information provides opportunities for restoration practitioners to optimize their efforts by prioritizing genotypes with specific beneficial characteristics.”

Madeline Kaufman, a coral researcher with the University of Miami and lead author of the study.

There has been a noted decline in the health of coral reefs around the world, caused by stressors such as pollution, overfishing, disease outbreaks, and climate change. Increasing sea water temperatures have caused coral bleaching events to occur more frequently and last for longer periods. Reef restoration techniques have become a common tool used to help restore coral reefs and their associated ecosystem services. Through the coral gardening process corals are fragmented to promote growth; however, this often leaves corals with lesions, making them more vulnerable to pathogens that can lead to mortality. In addition, thermal stress can slow or suppress wound recovery.

“From these results we now know that we should avoid fragmenting corals in areas with warmer water temperatures because the wound recovery rates are reduced there and the corals won’t be able to heal as quickly or efficiently.”

Ruben van Hooidonk, Coral Scientist at AOML

There is a pressing need for coral researchers and restoration specialists to identify coral genotypes with greater recovery potential and to assess the effect that increasing sea temperatures have on lesion repair. This will help scientists better understand how outplanted corals will be affected both seasonally and under ocean warming conditions.

“I hope that our research supports the incorporation of assisted migration into coral restoration efforts in the future. However, this experiment was limited to a laboratory setting and focused on a single species. Moving forward, it’s important to see if these results hold true in the field and with other species.”

Madeline Kaufman, a Coral Researcher with the University of Miami