Originally Published Wednesday, June 24, 2020 at NOAA NESDIS

As we move through the 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season, you will no doubt hear a lot about the Saharan Air Layer—a mass of very dry, dusty air that forms over the Sahara Desert during the late spring, summer and early fall.

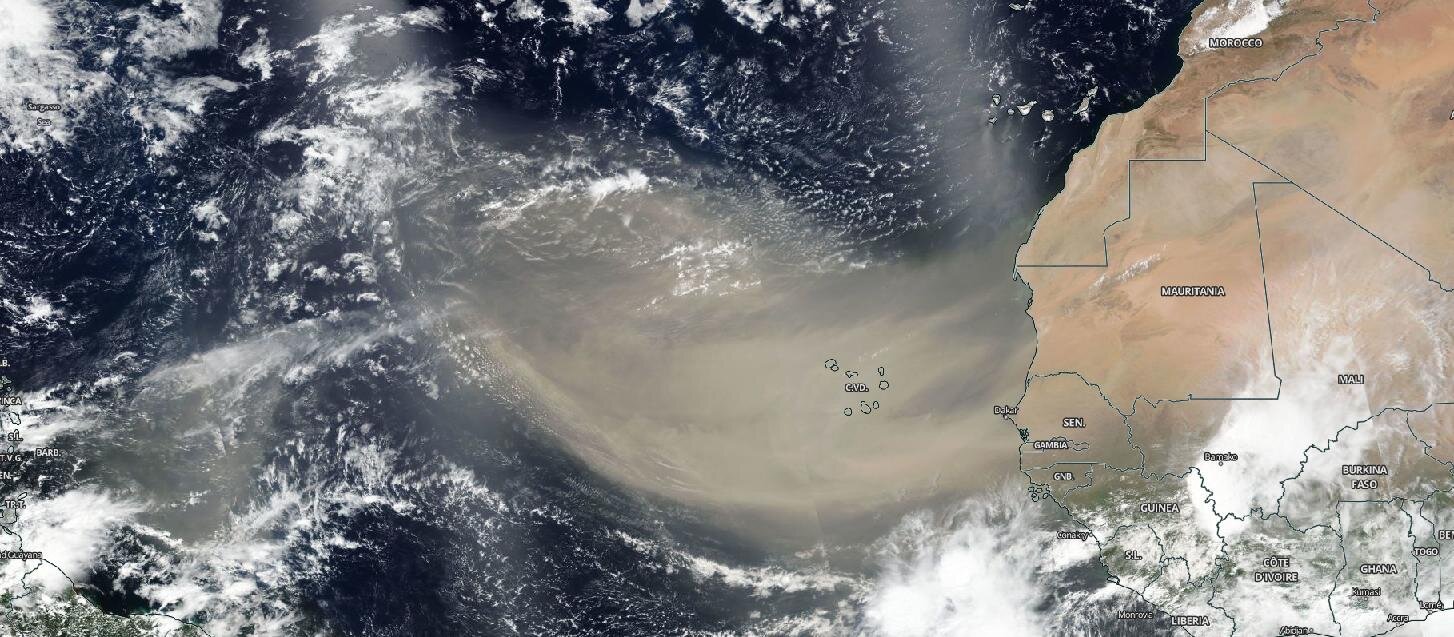

This layer can travel and impact locations thousands of miles away from its African origins, which is one reason why NOAA uses the lofty perspective of its satellites to track it. We sat down with scientist Dr. Jason Dunion, a University of Miami hurricane researcher working with NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, to ask him a few questions about the Saharan Air Layer.

NESDIS: What causes the Saharan Air Layer (SAL) to form?

Jason: SAL outbreaks can form when ripples in the lower-to-middle atmosphere, called tropical waves, track along the southern edge of the Sahara Desert and loft vast amounts of dust into the atmosphere. As the SAL crosses the Atlantic, it usually occupies a 2 to 2.5-mile-thick layer of the atmosphere with its base starting about 1 mile above the surface. The warmth, dryness and strong winds associated with the SAL have been shown to suppress tropical cyclone formation and intensification.

NESDIS: Is it common for dust from the Sahara to cross the Atlantic on a regular basis?

Jason: SAL activity typically ramps up in mid-June and peaks from late June to mid-August, with new outbreaks occurring every three to five days. During this peak period, it is common for individual SAL outbreaks to reach farther to the west—as far west as Florida, Central America and even Texas—and cover extensive areas of the Atlantic (sometimes as large as the lower 48 United States).

NESDIS: Which satellites do scientists use to track the dust and what information do the satellites give them?

Jason: Forecasters and scientists monitor and study the SAL using data from several satellites, including GOES-16, NOAA-20, and the NOAA/NASA Suomi-NPP. These satellites have a variety of visible, infrared and water vapor channels that can be used in combination to track the SAL’s warm temperatures, dry air, strong winds, and suspended dust. This information allows forecasters and scientists to continuously monitor the evolution of SAL outbreaks and their effects on the meteorology and climatology of the tropical North Atlantic.

NESDIS: Why do scientists and researchers track Saharan dust with satellites?

Jason: The SAL has unique properties of warmth, dry air and strong winds that can act to suppress hurricane formation and intensification. Thanks to recent advancements in satellite technology, we can better monitor and understand the SAL, from its formation over Africa, to its interactions with tropical cyclones, to its impacts on weather along the U.S. Gulf coast and Florida. Forecasters and researchers at NOAA routinely use satellite data to detect these aspects of the SAL and some of this information is ingested into models to improve forecasts. Satellites are also used to plan NOAA aircraft research missions to sample the SAL and better understand how the SAL can suppress tropical cyclones.

For more information on the Saharan Air Layer: