New research on stony coral tissue loss disease reveals similar “bacterial signatures” among sick corals and nearby water and sediments for the first time. Results hint at how this deadly disease might spread, and which bacteria are associated with it, on Florida’s Coral Reef.

This study is only the second peer-reviewed publication focused on characterizing the community of bacteria (the bacterial “microbiome”) associated with these sick corals. This is a critical effort because this widespread disease is believed to be caused by one or more bacterial pathogens.

Read the new study in Frontiers in Microbiology. Study authors hail from the University of Miami (UM), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Mote Marine Laboratory (Mote) and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. The project was supported by a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and by NOAA’s ‘Omics Initiative.

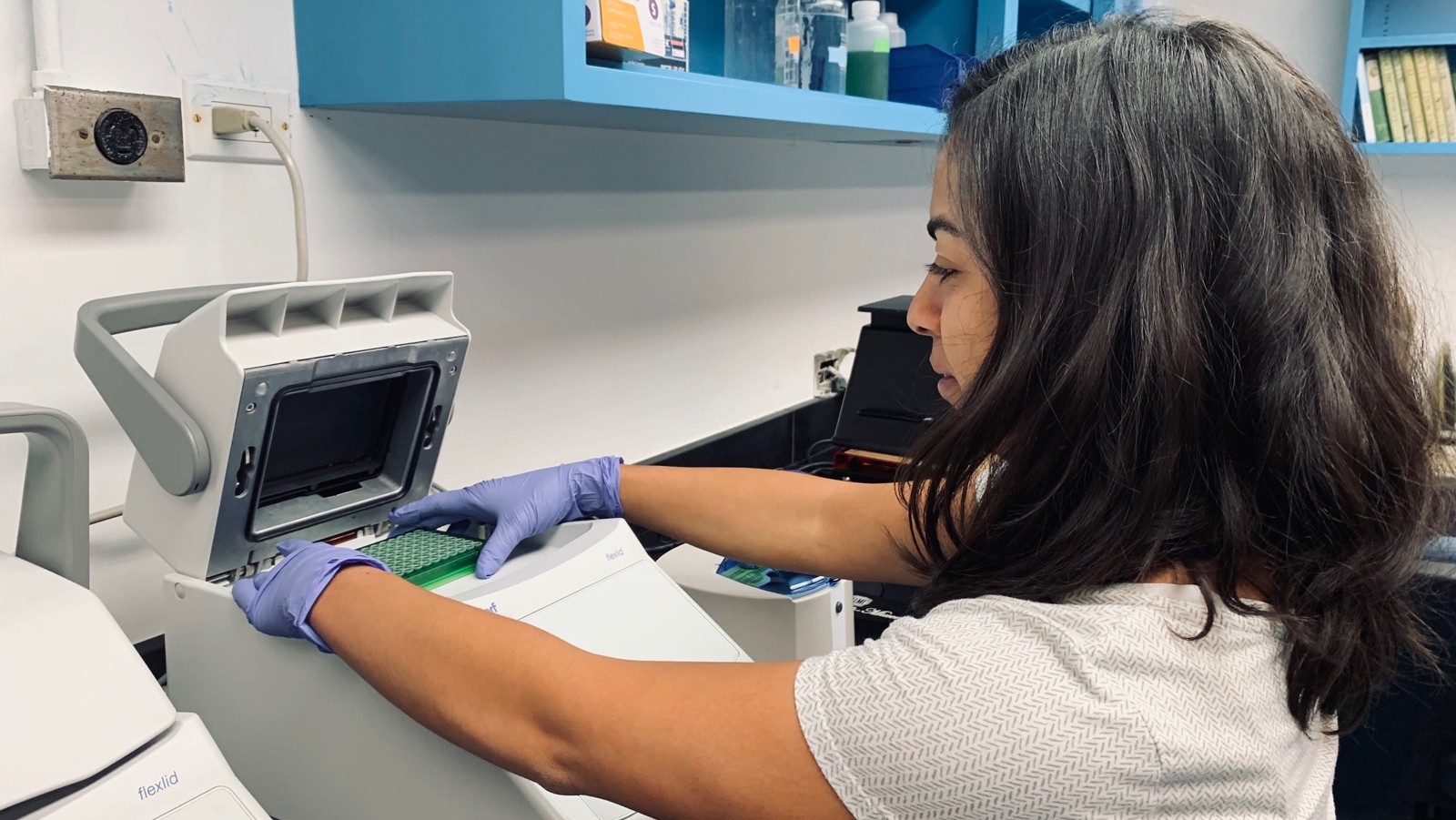

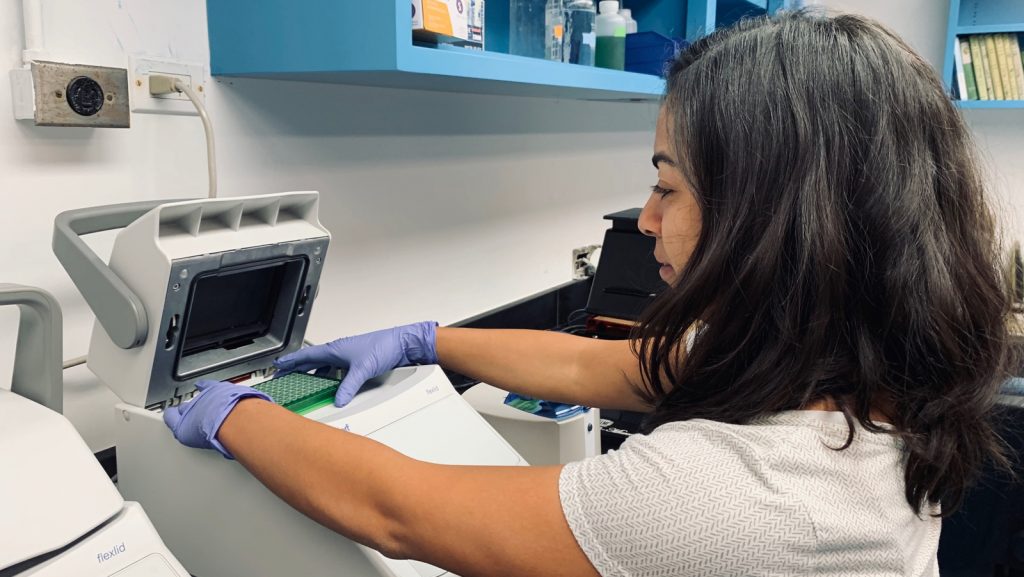

“We had two big questions in this study: One, could we try to detect which bacteria are associated with this disease, and two: Can we find those bacteria in the sediment and seawater, since these are two hypothesized sources of this disease?” said the paper’s first author, Dr. Stephanie Rosales, Senior Research Associate with the University of Miami’s Cooperative institute for Marine and Atmospheric Science, who analyzed bacterial genomic data from the field sampling effort conducted by Mote and FWC scientists.

Project partners sampled four susceptible coral species and nearby sediment and water in the Florida Keys and extracted DNA to identify groups of bacteria. They found that the bacterial groups Rhodobacterales and Rhizobiales were associated more prevalently with the disease lesions than healthy corals or healthy sections of sick corals. These bacteria might not be primary pathogens but their presence may be important nonetheless—for example, they might be taking advantage of corals that were already sickened by another pathogen. These bacterial groups were also found in the sediment and water, with Rhodobacterales elevated in areas with active or recent disease outbreaks compared with areas yet to show disease signs. This type of study can’t confirm the roles of these bacterial groups, but it narrows down key research targets for better understanding the disease while suggesting both water and sediment need to be considered in ongoing studies of the disease spread.