The waves lap at the bow of the RV Cable while glimmers of Cheeca Rocks, a bustling inshore patch reef, ebb and flow into focus below the surface. For eleven consecutive weeks, the Coral Program at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) laid anchor at this long-term monitoring site to deploy and maintain Benthic Ecosystem and Acidification Monitoring Systems (BEAMS) that simultaneously measure net community production and calcification. These metrics of reef metabolism are critical to assess whether Cheeca Rocks is undergoing growth or erosion. With each data point, BEAMS is shedding light on the resilience of Cheeca Rocks, and this experiment represents the longest continuous bout of fieldwork to date for AOML’s Coral Program, spanning June 26 to August 29, 2024.

Just a 20-minute boat ride from Islamorada, Cheeca Rocks is one of seven Mission: Iconic Reefs within the Florida Key National Marine Sanctuary and is a part of the National Coral Reef Monitoring Program.

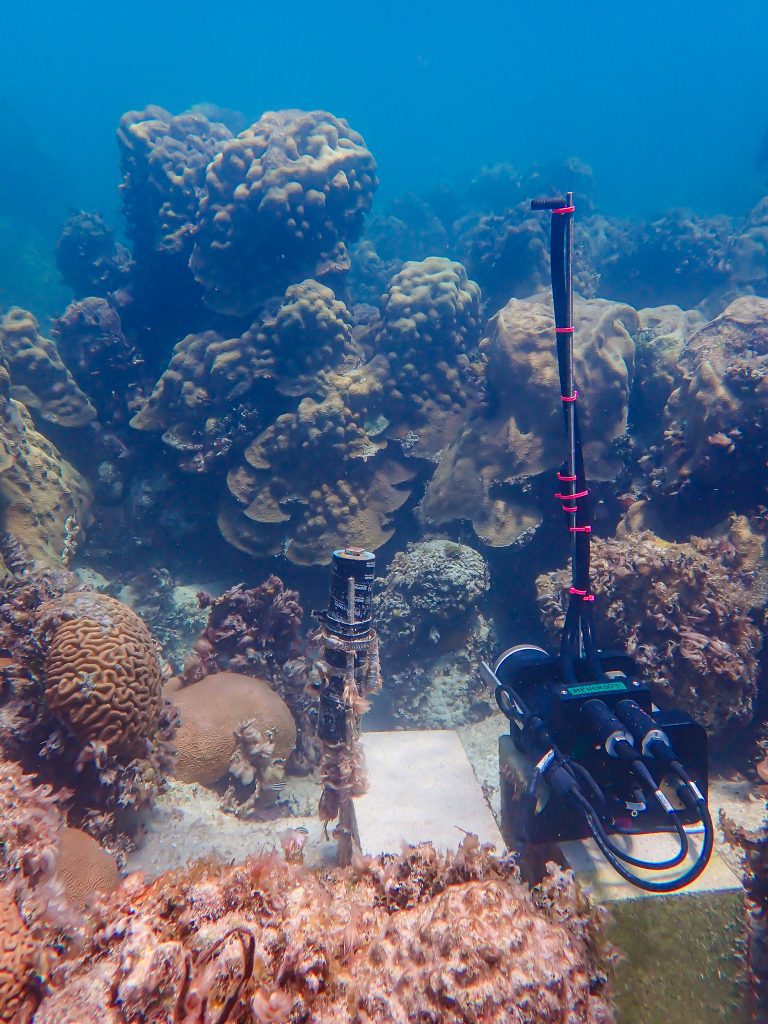

The BEAMS equipment, on loan from developers at Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, allows the Coral Program to collect environmental data that quantifies the metabolic rates of the reef, specifically net community production and calcification, under natural conditions. BEAMS is the size of a desktop computer and works by pumping seawater over a set of sensors that measure differences in pH, oxygen, and current movement from two heights: one at the seafloor and one just above the seafloor. It also collects temperature profiles, salinity measurements, and depth readings. Co-deployed are instruments like the Acoustic Doppler Profiler, which measures water currents, and the ECO-PAR, which gauges available sunlight and distinguishes stormy days from sunny days.

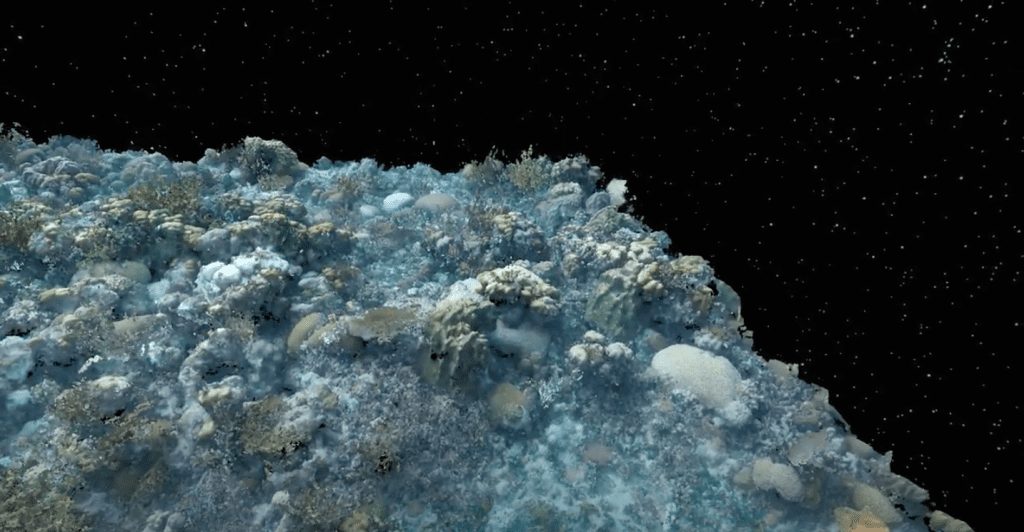

Leading the mission are Coral Program members, John Morris, Ph.D., and Heidi Hirsh, Ph.D. Each week, the team returns to the site to pull the equipment from the seafloor, offload data, swap batteries, and re-deploy. After reassembling the equipment on cinder blocks with zip ties, divers use the rest of their bottom time to gather water samples and capture thousands of images that are pieced together to create a three-dimensional model of the reef, known as a photomosaic. By creating photomosaics each week, researchers can visualize how a reef changes over time and assess the health of individual coral colonies.

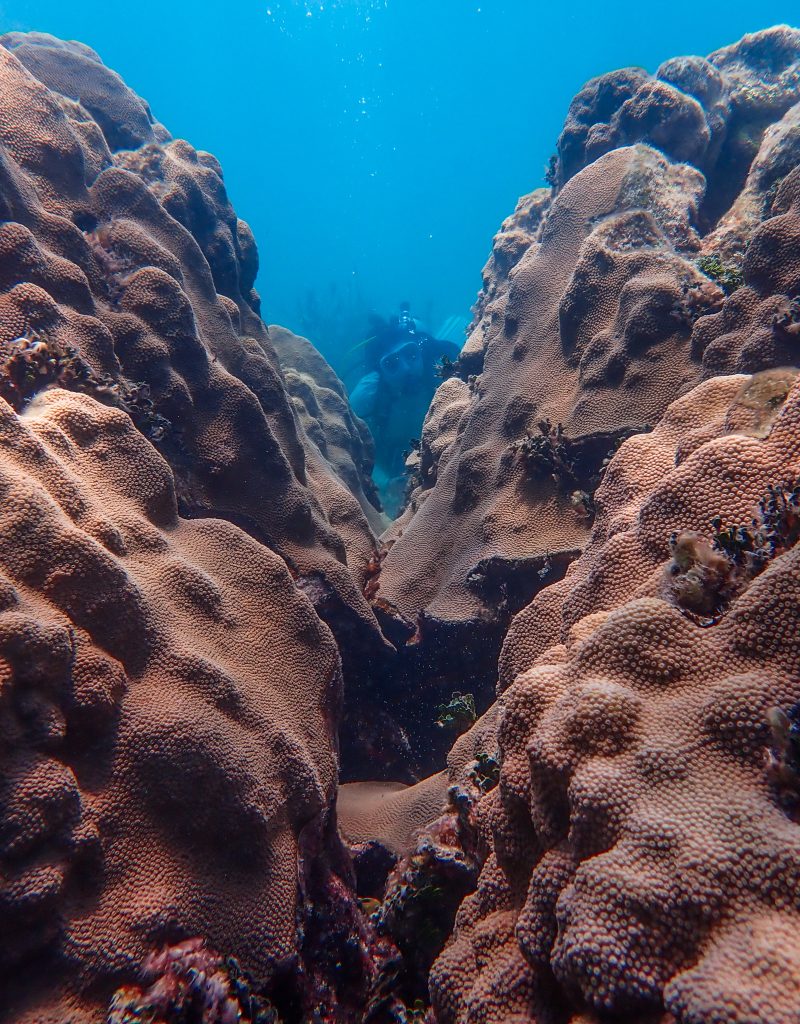

Resting a mere 15 feet below the surface, Cheeca Rocks was chosen as the ideal study site with hopes that the resulting data will help scientists to understand why it and other inshore patch reefs have shown greater resiliency to environmental stressors like bleaching, disease, and overfishing.

That’s not to say that Cheeca Rocks has been without periods of extreme stress responses. In the summer of 2023, a marine heat wave imperiled Florida reefs, leaving many colonies bleached, diseased, and even dead. For scientific divers that frequent Cheeca Rocks, the reef was almost unrecognizable: where healthy, colorful coral mounds once rose from the substrate, ghostly white corals took their place.

While some corals were able to recover, there was also significant mortality. Throughout the 2024 field season, scientists were on the edge of their seats, wondering if corals in South Florida and the greater Caribbean would be subject to the same thermal stress as 2023. As the final days of the summer 2024 field season came to a close, scientists breathed a sigh of relief.

“Episodic rainfall and summer storms created large variability in seawater temperatures that may have provided coral communities with periodic thermal refugia. As a result, coral communities experienced some paling but avoided widespread bleaching,” said Morris.

What makes Cheeca Rocks resilient in the face of environmental stressors? Scientists are yet to put their finger on the reasons, but continued monitoring with photomosaics and instruments like BEAMS are shedding light on this mystery every day.