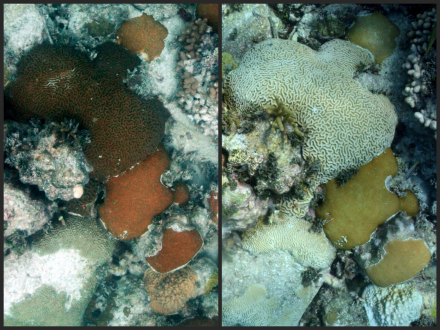

2014 was a relatively warm summer in South Florida, and local divers noticed the effects of this sustained weather pattern. Below the ocean surface, corals were bleaching. In the month of August, the Coral Bleaching Early Warning Network, jointly supported by Mote Marine Lab and NOAA’s Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, received 34 reports describing paling or partial bleaching and an additional 19 reports indicating significant bleaching. Scientists continue to monitor the impact of this severe bleaching event to determine the extent of coral mortality.

This image, taken on November 13, 2014 by the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, shows a severely bleached pillar coral at Sand Key in the Florida Keys. Images like this one indicate that some regions and species will definitely be affected. Pillar coral is one of the species of coral listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

AOML Coral Ecologists Derek Manzello and Jim Hendee provide insight as to how the environmental conditions they are tracking indicate that a mass bleaching event is possible and even likely in the Florida Keys.

What is coral bleaching?

Coral colonies are made up of hundreds or even thousands of genetically identical individuals called polyps. These polyps have microscopic colorful algae called zooxanthellae living within their tissues. The zooxanthellae work like an internal symbiotic vegetable garden, carrying out photosynthesis and providing energy to their coral hosts, which helps reef-building corals create reef structures. When a coral bleaches, it expels its zooxanthellae, and can die within a matter of weeks unless the zooxanthellae populations are able to recover. The term bleaching is used because the dazzling colors of living corals are due to the zooxanthellae in coral tissue, and when zooxanthellae are lost, corals appear white, or “bleached.”

What causes coral bleaching?

It is well established that elevated sea temperatures cause widespread coral bleaching. Warmer waters “stress” corals and trigger coral bleaching.

There are two types of heat stress that can trigger bleaching: (1) short-term, acute temperature stress (several days of very high water temperatures) and, (2) cumulative temperature stress (weeks of consistent moderately elevated water temperatures). Scientists have documented that coral communities around the world have different heat stress thresholds that typically trigger bleaching in response to heat stress. Scientists rely on long-term observing stations co-located with coral reefs to identify the specific conditions that correlate to bleaching within different regions.

What specifically triggers bleaching of coral found in the FL Keys?

Using long-term in situ datasets such as the Coastal-Marine Automated Network, or C-MAN, stations in the Florida Keys, AOML scientists identified specific patterns of warm waters on coral reefs that tend to precede bleaching

events. The indices that proved to be the most reliable indicators for bleaching for the Florida Reef Tract are maximum monthly sea surface temperature and the number of days >30.5 C (86.9 F).

What patterns have scientists noticed leading up to this most recent bleaching event?

Data from the Molasses Reef C-MAN station showed that the winter of 2014 was the warmest on record since these stations began recording data in 1988. The second warmest winter on record was the winter of 1996/97, which preceded back-to-back bleaching years in the Keys (1997/98) and was the worst bleaching event ever documented in the Florida Keys. The most recent significant bleaching event in the Florida Keys occurred in 2005, and there have been mild localized bleaching events since then.

The warm winter and warm water temperatures this spring caused scientists to start watching the long-term average water temperatures at these stations to see if the average daily temp was regularly reaching or exceeding 30.4 C, the trigger point for previous bleaching in the FL Keys. The Molasses Reef C-MAN site quickly approached this temperature threshold in July and August. Average temperatures were also warmer than normal at the Fowey Rocks C-MAN station and the Cheeca Rocks Atlantic Ocean Acidification Testbed in the northern Keys. With water temperatures now exceeding this threshold for more than thirty days, and reports of bleaching beginning to pour in, there are concerns about widespread bleaching throughout the region. To assess the extent of the bleaching event, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary has been working with its partners to monitor the current state of corals along the reef tract.

Jim Hendee is the acting division director of AOML’s Ocean Chemistry and Ecosystems Division. Jim leads the coral group at AOML and studies the environmental conditions that cause ecosystem-wide changes on coral reefs using in situ observing stations. Derek Manzello is a coral ecologist at AOML and leads research of the impacts of ocean acidification on coral reefs. Derek also studies the impact of other changes in environmental conditions on reefs such as temperature and tropical storm impacts.

Originally Published September 2014 by Shannon Jones