Feature image photo credit: NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer

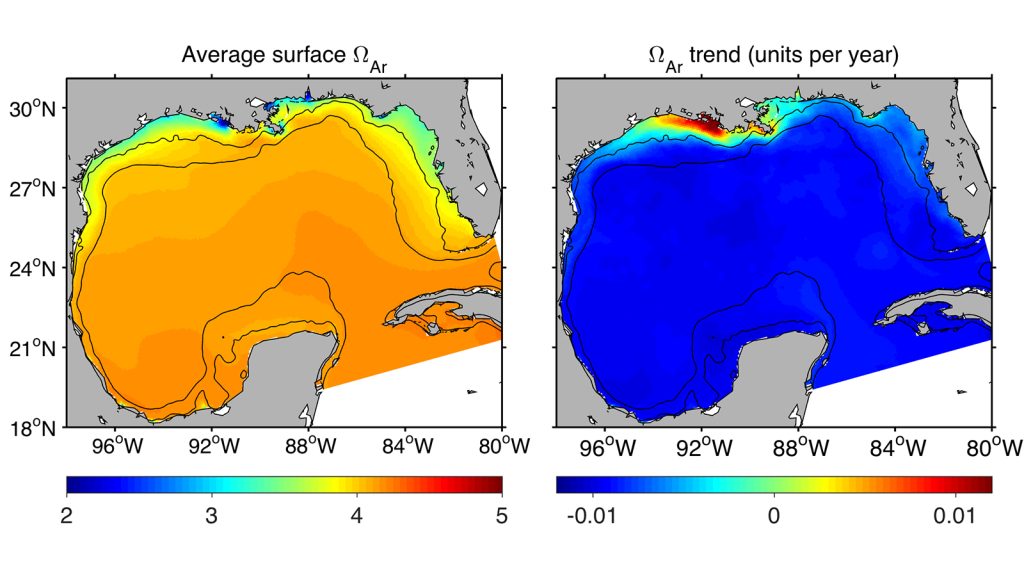

A new study by scientists at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) and Northern Gulf Institute (NGI) has revealed the alkalinity of river runoff to be a crucial factor for slowing the pace of ocean acidification along the Gulf of America’s northern coast. This valuable, first-time finding may be indicative of ocean carbon chemistry patterns for other U.S. coastal areas significantly connected to rivers.

The research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, used models to identify the main drivers of ocean acidification for different regions of the gulf. They provide evidence that river alkalinity has counteracted the progression of ocean acidification for coastal areas along the gulf.

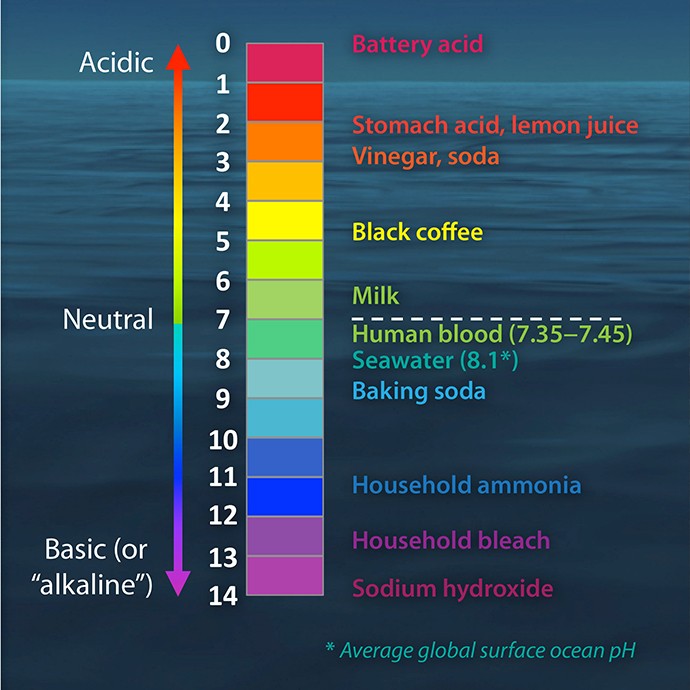

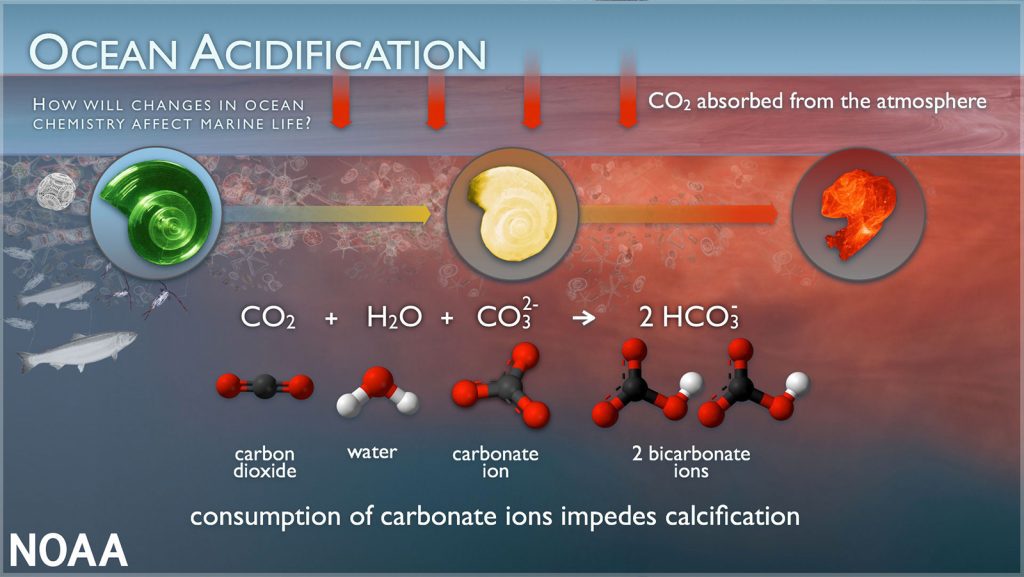

Ocean acidification refers to a reduction in seawater pH over time, mainly caused by increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere being absorbed into the ocean. Seawater chemically reacts with carbon dioxide to form carbonic acid, causing the ocean to become more acidic.

These changes in ocean chemistry negatively impact marine species such as corals and shellfish by impairing their ability to grow and survive. As the ocean’s pH level decreases, there is also a reduction in the aragonite saturation state, i.e., the water conditions that will more likely dissolve calcium carbonate, one of the materials used by shells and coral skeletons to form their structure.

Corals and shellfish need a higher aragonite saturation state and less acidic waters, i.e., higher on the pH scale, to thrive. If waters become too acidic, less coral reef habitat will be available for fish and other reef dwelling animals, diminishing biodiversity and marine ecosystem health.

The Mississippi River has a relatively high level of alkalinity for a freshwater body. Over recent decades, agricultural practices such as liming (adding neutralizing materials to lower soil acidity) and water quality improvements have contributed to the increased water alkalinity in the Mississippi River system. Alkalinity acts as a neutralizing factor to make a solution less acidic and more basic or alkaline.

“Our study showed that river alkalinity inputs from the Mississippi River can offset the progression of ocean acidification in northern coastal areas of the Gulf of America. We can expect river alkalinity to have a similar counteracting effect on ocean acidification in other US coastal regions, since the dominant pattern for US rivers is alkalinization,” said Fabian Gomez, a research scientist at AOML and NGI.

Ocean acidification is a major environmental stress factor that contributes to the degradation of valuable marine resources in the gulf. A recent report by NOAA’s Office of Coastal Management highlighted the economic value of the Gulf of America’s coastal and marine ecosystems: they support approximately 598,000 workers and are the largest contributor to America’s blue economy, with an estimated $104 billion dollars coming from oil and gas production, marine shipping, and the fishing industry.

NOAA’s research to better understand ocean acidification will help preserve and manage coral reefs and other marine species that gulf coastal communities depend on for fishing, tourism, and other economic drivers in the region.