In a recent study published in the journal Coral Reefs, scientists at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) found that staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) fragments exposed to an oscillating temperature treatment were better able to respond to heat stress caused by warming oceans.

With the rise in ocean temperatures and more frequent bleaching events, research is being conducted on techniques to improve the survivorship of nursery-raised corals outplanted on degraded reefs. Previous studies have shown that corals growing in environments with natural temperature variability experience less bleaching when exposed to increased temperatures.

Coral bleaching, a process in which the colorful algae living inside the coral’s tissue is expelled, leaving the coral white in appearance, can occur as a response to stressors like increased water temperatures. Bleached corals are in a stressed state, vulnerable to disease but may sometimes recover.

“We want to increase the efficiency and efficacy of these (restoration) efforts, and ultimately ensure that the corals that are placed back out on a reef have the greatest chance of enduring the stressful conditions they will face in the future”, said Ian Enochs, senior author of the study, lead scientist of the Coral Program at AOML.

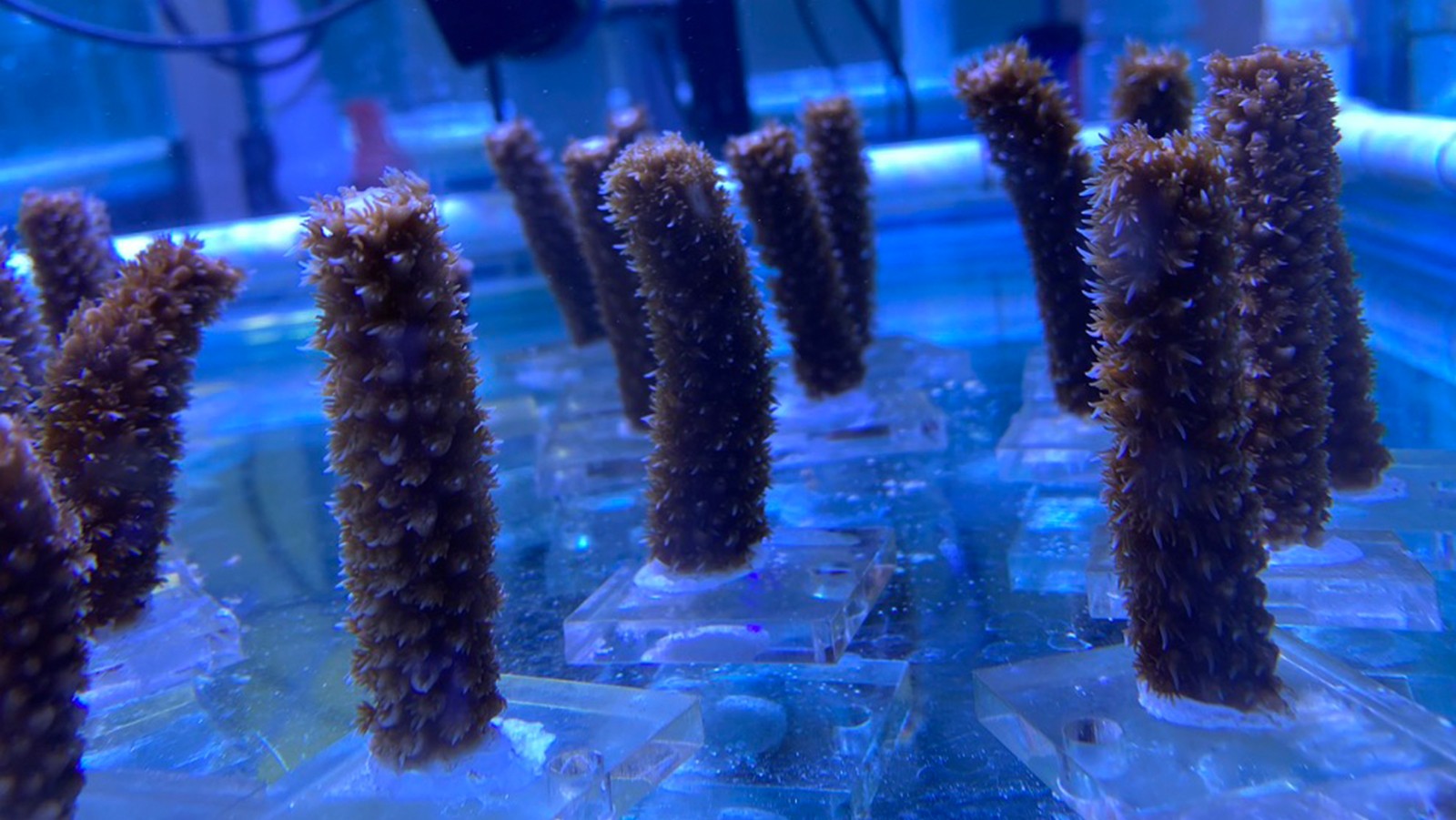

Scientists at AOML and the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS) at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science experimented with a stress-hardening technique that mechanized the acclimation of coral fragments to stressful temperature conditions. Caribbean staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) fragments were exposed to either a variable temperature regime (i.e., stressful temperatures that fluctuated twice per day from 28 to 31°C) or a static temperature (that remained at 28°C) for three months. All coral fragments were then exposed to a heat-stress treatment. Scientists found that the variable temperature-treated coral group had a healthier physiological response and was better able to endure thermal stress, succumbing to bleaching more slowly than the non-variable treated group.

“This ‘training’ regime is similar to an athlete preparing for a race. We were able to demonstrate that this temperature treatment can boost the corals’ stamina to heat stress”, said the study’s lead author Allyson DeMerlis, a PhD student at AOML and the University of Miami Rosenstiel School for Marine and Atmospheric Science.

This research will be used to guide efforts to improve the success of restoration efforts for staghorn coral, currently listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act. The research also supports coral reef resiliency at a time when global warming remains a top threat to marine ecosystems.

The study was funded by NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program.