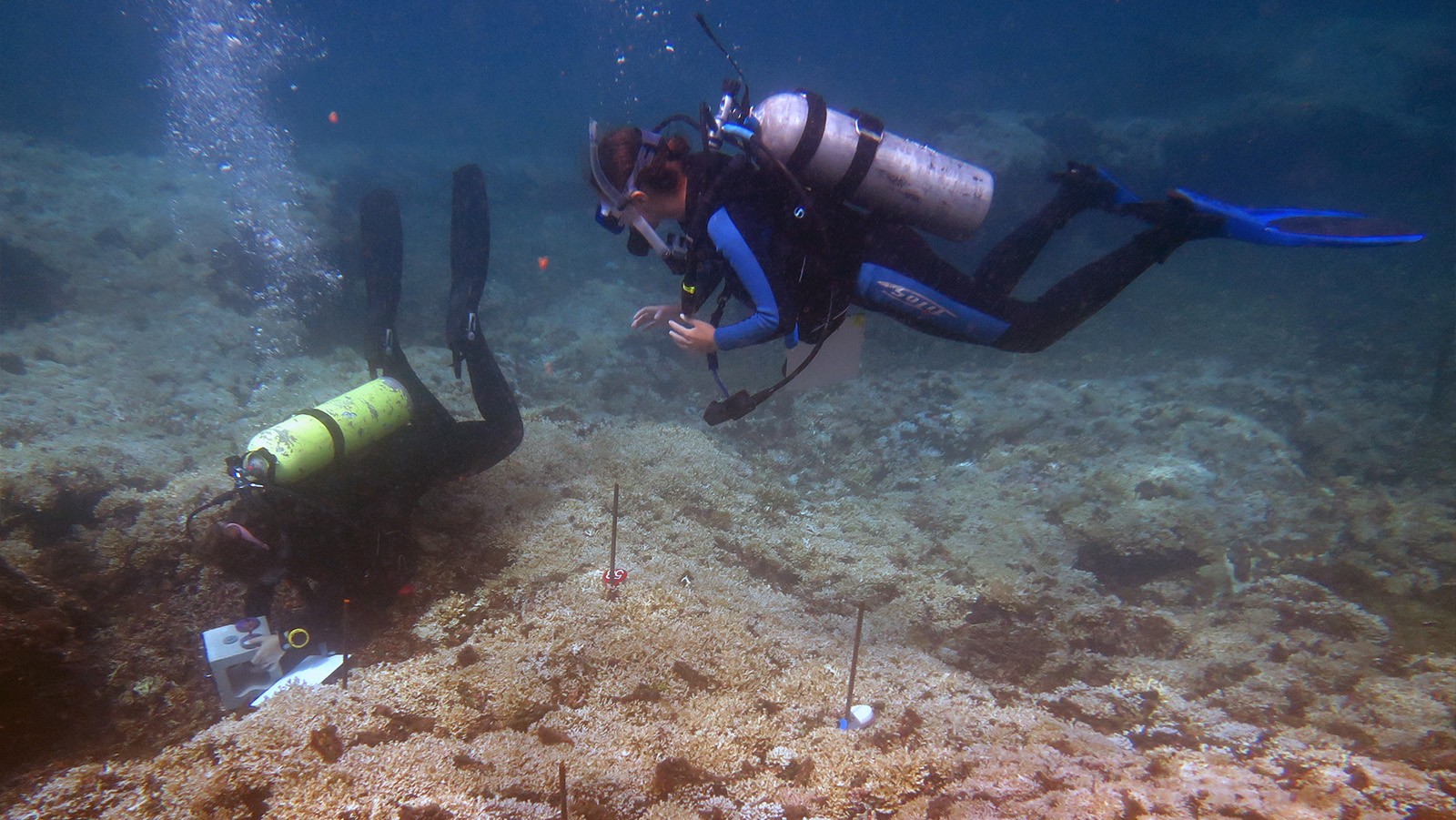

Feature image photo credit: Dr. Lauren Toth, USGS

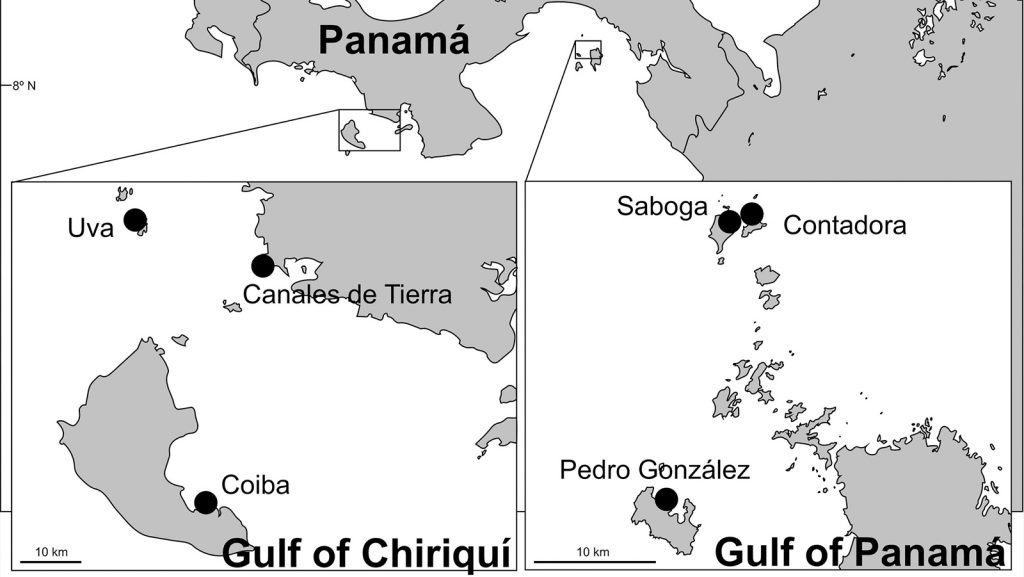

Trying to predict how coral reefs will respond to warming oceans and a changing climate may be considered a daunting task for scientists. In the face of this challenge, scientists at AOML recently published a study that characterizes the organisms and processes that lead to coral reef accretion (build up) and bioerosion (break down) in the dynamic environments of the Gulf of Panamá and Gulf of Chiriquí in the eastern Pacific.

So how does a reef take shape and create pillars, ridges, and mountainous structures? Ocean conditions such as temperature, acidity, and available nutrients in the water play a role, as do marine organisms called “bioeroders” that graze the coral for algae (grazers), create holes in the coral surface (microborers), or create holes in its internal structure (macroborers). Although grazing and erosion diminish reefs, they also allow space for new coral to form through the deposition of calcium carbonate–a process called “calcification.”

“Reefs are fighting a battle on two fronts as the changing climate decreases habitat growth while simultaneously increasing erosion. The stakes of this battle are high, with the very persistence of reefs and the ecosystem services that they provide in question,” said Ian Enochs, a research ecologist at AOML and lead author of the study.

Scientists studied the marine organisms and processes mentioned above using bioerosion accretion replicates (BARs) made from stony coral (Porites) skeletons (the same material that makes up the reef), that were deployed to reefs in the gulfs of Panamá and Chiriquí. After two years, they scanned the BARs using computed tomography (CT) to better understand bioerosion and accretion at these reef sites.

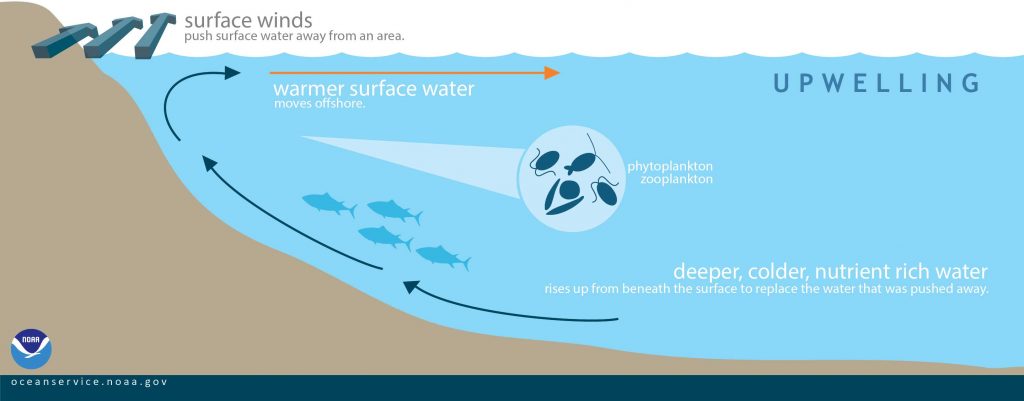

The study revealed that in both gulfs, external bioerosion by grazers such as parrotfish and urchins was the major process altering coral reef habitat, with higher rates of erosion and habitat loss observed in the Gulf of Chiriquí. One difference in environmental factors between the gulfs was the greater amount of upwelling (movement of deeper cold nutrient-rich waters to the surface) in the Gulf of Chiriquí that may have provided a food source for calcifying animals, as well as accelerated macroboring, leading to a less structurally stable reef developed on sediment (instead of solid reef material).

Keeping up with sea level rise and other stressors brought on by climate change presents a challenge for reefs struggling to grow and adapt to changes in the environment. The interaction of reef structure, habitat biodiversity, and ocean conditions can lead to a variety of ecosystem outcomes that are difficult to predict. A holistic approach to examining the impact of environmental conditions on all habitat-altering organisms is key to understanding reef persistence in the eastern Pacific and global ocean.

Reference:

Enochs, I.C., L.T. Toth, A. Kirkland, D.P. Manzello, G. Kolodziej, J.T. Morris, D.M. Holstein, A. Schlenz, C.J. Randall, J.L. Maté, J.J. Leichter, and R.B. Aronson. Upwelling and the persistence of coral-reef frameworks in the eastern tropical Pacific. Ecological Monographs, 91(4):e01482, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1482