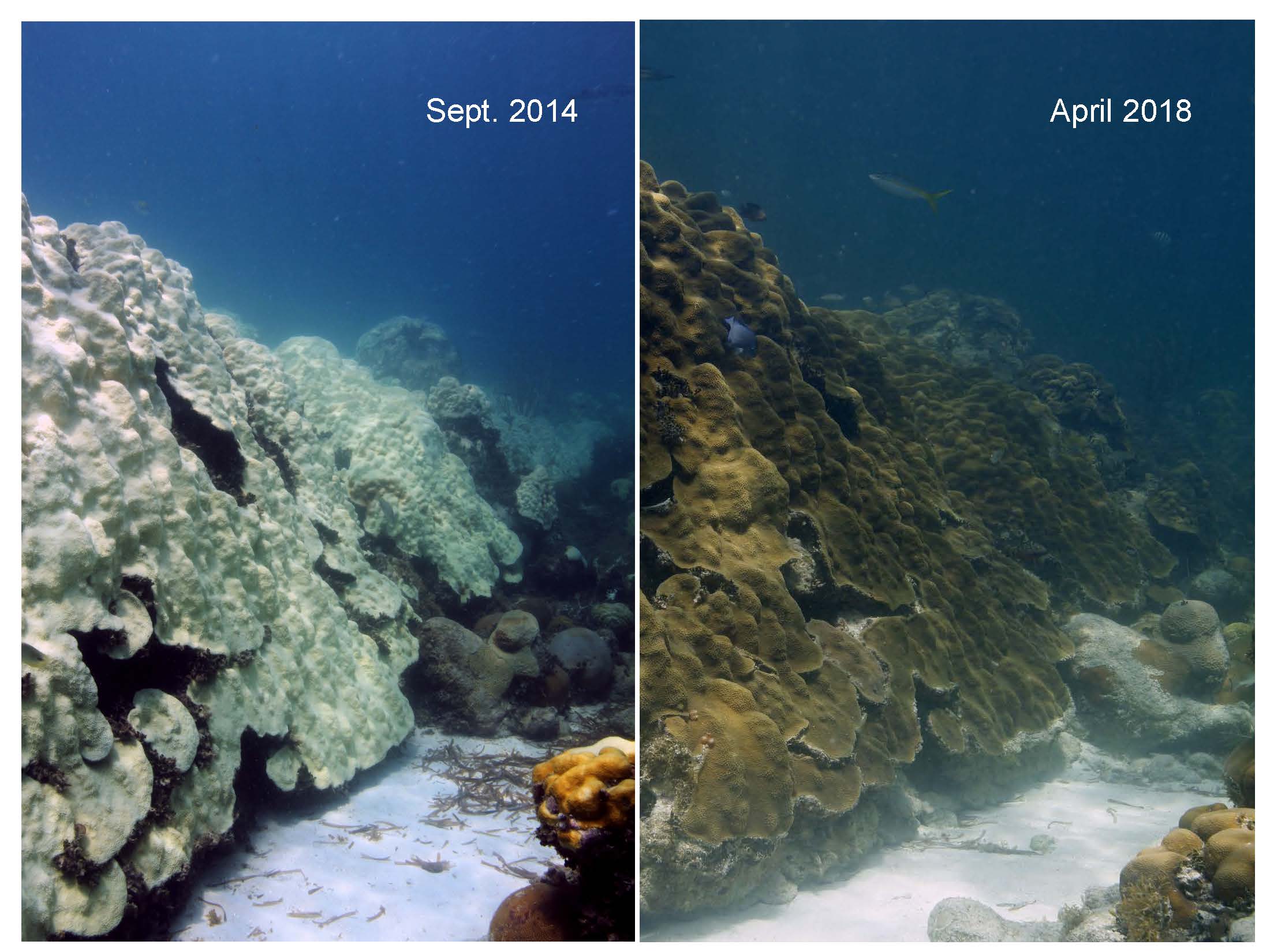

A recent study by AOML and partners identified coral communities at Cheeca Rocks in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary that appear to be more resilient than other nearby reefs to coral bleaching after back to back record breaking hot summers in 2014 and 2015 and increasingly warmer waters. This local case study provides a small, tempered degree of optimism that some Caribbean coral communities may be able to acclimate to warming waters.

Cheeca Rocks is a shallow inshore patch reef near Islamorada, Florida that has much higher coral cover than the surrounding offshore reefs of the Florida Keys. As part of the National Coral Reef Monitoring Program, which is co-funded by NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program and Ocean Acidification Program, AOML researchers used high resolution underwater imagery to create a mosaic of the reef scape before, during, and after bleaching. These mosaic images allowed high resolution monitoring of changes in over 4,000 coral colonies.

Bleaching happens when corals are exposed to heat stress, usually when temperatures exceed their long-term summer maximum by 2 to 3 degrees Fahrenheit for more than a month. Heat-stressed corals expel their symbiotic photosynthetic algae (zooxanthellae) that live inside their tissue and provide much of their energy demands. Corals will die if they are without their algal symbionts for an extended period of time. Corals can survive bleaching if temperatures return to average but are then more susceptible to disease and have depressed reproductive output.

Derek Manzello, a co-author on the paper said:“While this site has shown bleaching resistance, this does not necessarily mean that it will be able to resist more severe bleaching events or the ongoing 4 year coral disease event that has impacted south Florida coral reefs since 2014. We are currently tracking the progression of the disease, which first appeared at Cheeca Rocks in March 2018.”

Understanding how this monitoring site responds under thermal stress is integral to understanding the long-term resilience scenarios for ecosystem and resource management of Caribbean coral species. NOAA scientists will continue to monitor Cheeca Rocks in order to confirm this as an anomaly or a trend that can be further quantified. Further studies will focus on the environmental and biological factors that help these corals to survive under increasing stress.