Marine debris is one of the most widespread pollution problems facing the world’s ocean. Huge amounts of plastic, metal, rubber, derelict fishing gear, and other lost or discarded items enter the ocean every day, negatively impacting the marine environment. Debris items can be carried far from their origin, which makes it difficult to determine exactly where an item entered the ocean. A recent study off the Florida coast might help identify how ocean currents and winds play a role in the distribution of these material over hundreds of miles.

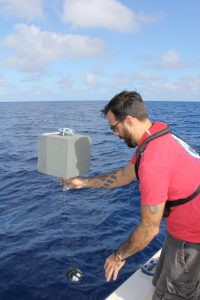

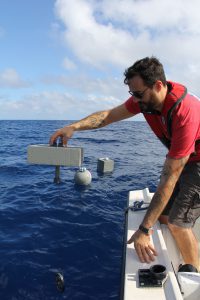

Researchers at AOML, NESDIS CoastWatch, and the University of Miami are currently exploring how the distribution of marine debris is affected by both ocean currents and wind. During a recent experiment, scientists deployed several prototype drifters in the Florida Current off the coast of Miami to simulate commonly found debris of varying weights and shapes. These drifters carry GPS transmitters that provide their location four times per day.

Throughout the months of January and February, these drifters will be tracked to test their floatability and transmission capabilities. Several similar experiments are planned, to assess how debris trajectories are impacted under varying ocean dynamics and wind fields. Ultimately, scientists anticipate that this project will lead to a better understanding of the trajectories in the ocean of floating debris, in addition to some marine species of algae and marine larva.

In addition to marine debris, the scientists creatively designed and deployed a drifter simulating a bed of Sargassum, a common type of algae usually found in the tropical oceans, including the Florida Current and Gulf Stream. Over the last decade, there have been extreme occurrences of Sargassum in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of America, and tropical Atlantic. Recurrent accumulations of Sargassum cause significant economic and environmental problems, including the closing of beaches, disruption of marine navigation, and negative impacts on sea turtle nesting behavior. However, the geographical source of these algae is still being investigated, making the likelihood of future accumulation difficult to predict.

Depending on ocean currents, wind velocity, and object shape, weight, and buoyancy, marine debris could follow countless different trajectories and travel at different speeds. The results of this study have the potential to lead to collaborative projects that will enable NOAA and the wider scientific community to estimate the location of where existing debris first entered the ocean and where new debris will travel after it enters the ocean.