Dredging stirs sediment plumes that cloud the water column, block sunlight, and blanket coral reefs and other ecosystems with contaminants, pathogens, and microbes reintroduced from layers of buried seabed.

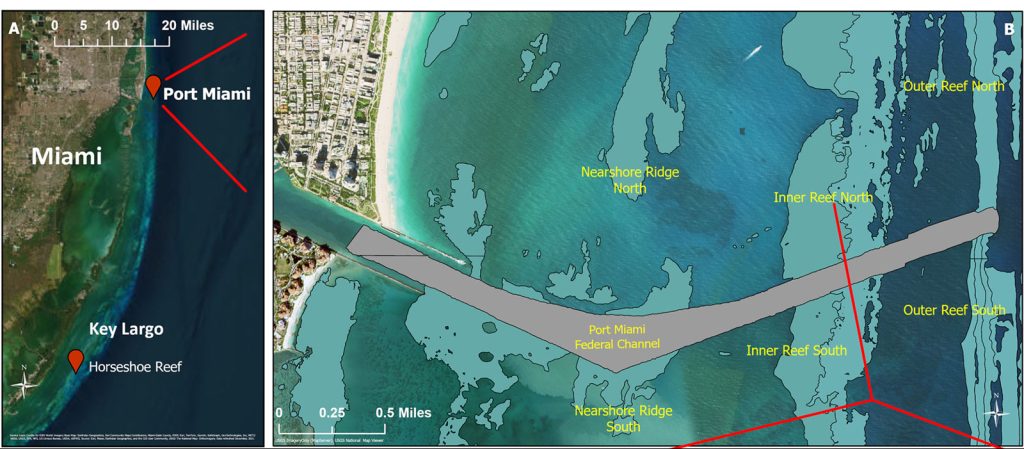

Dredging is known to have drastic effects on coral reefs, but a new study led by scientists at the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (CIMAS), NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML), and NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service Habitat Conservation Division now indicates significantly lower survival and settlement of coral larvae, and ultimately reduced reproductive success, when exposed to suspended sediments from recently dredged areas, i.e. Port Miami.

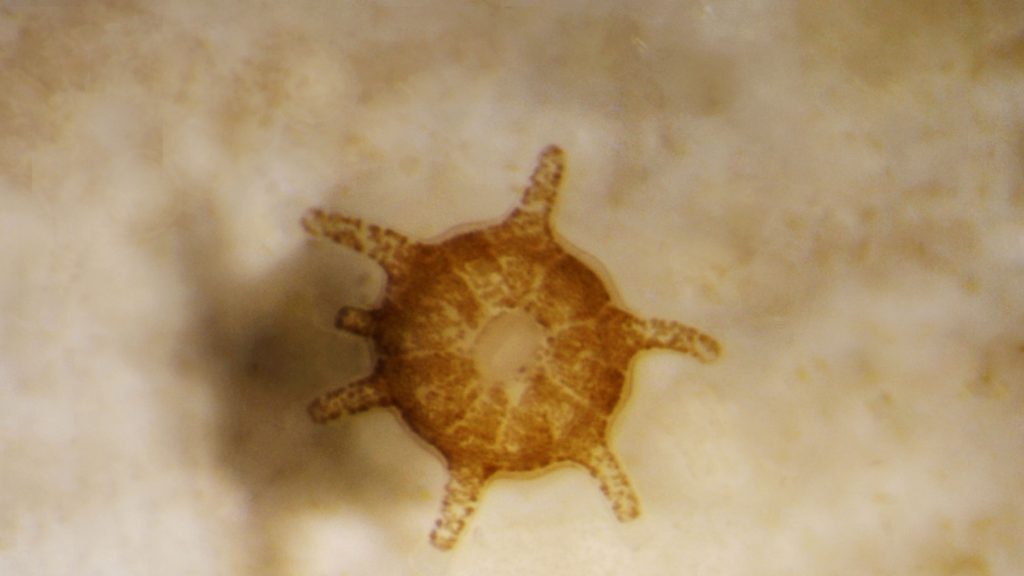

Coral reefs protect coastlines from storm surge and erosion while hosting rich and complex biodiversity, but increasing environmental and human stressors now threaten these crucial ecosystems. Exposure to suspended sediments and increasing turbidity can negatively impact corals through all of their life stages. However, only a few studies have investigated the effects on early life stages of corals, such as planulae (i.e. coral larvae) that eventually settle on a substrate and mature into coral polyps.

To examine the effects of suspended sediments on coral larvae, scientists exposed coral larvae from the species Orbicella faveolata (mountainous star coral), listed under the Endangered Species Act, to different levels of sediments extracted from two sites: a shallow, inshore coral reef in the Florida Keys and a reef near the recently dredged Port Miami.

Orbicella faveolata coral larvae were exposed to low and high doses of sediments collected from the two sites and compared with a control treatment (i.e. no sediment) to determine the effects on larval survival, settlement on a rubble substrate one week after exposure, and respiration. No key differences in respiration rates were observed across the treatments, and there was no significant impact in survival on larvae exposed to sediments from Horseshoe Reef and relatively low-doses of sediments from Port Miami, suggesting some initial tolerance to sedimentation.

However, larvae exposed to the higher dose of sediments collected from the Port Miami experienced a drastic decrease in survival, and after a week, exposure to both low and high doses of Port sediments led to a significantly lower ability of coral larvae to settle.

A difference in survival and settlement rates between larvae exposed to suspended sediments and those exposed to none (i.e. the control treatment) could be expected, but the greater impacts observed among coral larvae exposed to sediments from near a recently dredged site compared to those of a naturally-occurring reef emphasizes the greater harm that port and inlet sediments may have as a result of differences in their physical, chemical and biological composition.

Xaymara Serrano, Ph.D. and Stephanie Rosales, Ph.D., lead authors on the study and CIMAS scientists, analyzed the microbial communities of sediments collected from the two sites using a protocol known as “gene amplicon sequencing,” enabling the researchers to amplify the microbial genetic material present in a sample. Analysis revealed that sediments from the two sites were made up of different microbiomes, and the key difference was the relatively high abundance of a bacteria group called Desulfobacterales in the Port sediments – a bacteria commonly linked to coral disease.

“This study’s findings really highlight the importance of setting temporary moratoriums (“environmental stand-down windows”) during dredging operations which span the months of peak coral spawning, as well as an additional period after spawning to prevent negative effects on larval settlement.” – Xaymara Serrano, Ph.D.

These findings ultimately underpin the necessity to strategize and manage dredging projects in a way that avoids and minimizes the impacts on corals and coral reef habitats – including the most vulnerable life stages. Inappropriate management of dredging operations can result in preventable coral losses, and unnecessarily high adaptive management and mitigation costs to offset impacts.

Importantly, the suspended sediment exposure in this study was performed within a 24-hour period. As the two major dredging projects in southeast Florida plan on expansions that will take multiple years (Port Everglades and Port Miami), implementing long-term benthic monitoring plans for detecting increases in sedimentation, turbidity, and exposure to pathogenic bacteria and other contaminants is crucial.