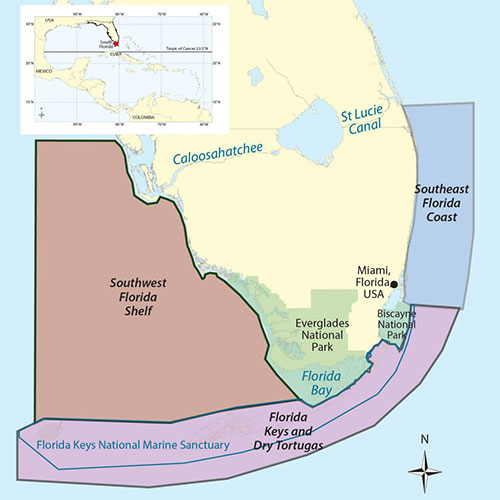

South Florida is comprised of 350 miles of the only barrier coral reef in North America – and the third largest in the world. 1,800 miles of shoreline is lined with mangroves in the Florida Keys alone, which provide coastal protection from storms and support juveniles of commercialized fish species.

The region sustains the largest contiguous seagrass community recorded in the northern hemisphere dispersed from Florida Bay on the West coast to Biscayne Bay on the east. The Everglades covers 2 million acres of the largest subtropical wetland in the U.S. supporting water storage, flood control and a rich biodiversity.

“Fossil reefs” encrust approximately 65,600 square miles of the West Florida Shelf expanding out into the Gulf region where commercial and recreational fisheries spawn.

That is the scale of South Florida ecosystems.

The Everglades is comprised of marsh, mangroves, and rivers extending well beyond the National Park south to Florida Keys – and as far north as Orlando, Florida.

Yet coral cover has declined by an estimated 90% across Florida since 1970. Harmful algal blooms (HABs) and de-oxygenation events threaten habitats and biological communities across the Gulf Coast. The extent of seagrass meadows have declined by up to 50% across different portions of South Florida – with heat stress driving mass die-offs across all five major Florida estuaries between 2011 and 2016.

To understand the health and status of these crucial, vastly different, yet interconnected regions requires long-term monitoring and assessing changes in water quality, developing ecosystem indicators that effectively capture these changes across time. At AOML, scientists have been doing this for 27 years.

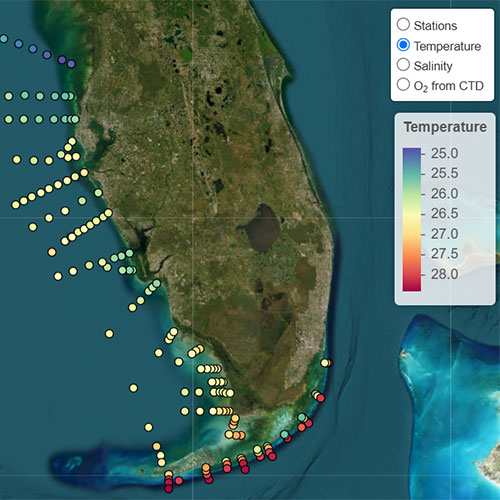

Each point represents a station where the team collects observations. With these stations compiling into lines known as transects, scientists sample each transect from inshore to offshore. The varying colors here represent the sea surface temperature at each station from the November 2024 cruise.

In January, scientists at the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML), the Cooperative Institute of Marine and Atmospheric Science (CIMAS), Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the University of South Florida, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, and Mote Marine Lab completed the first of six cruises planned for the year as part of the South Florida Ecosystem restoration program.

The goal of these expeditions is to investigate regional processes driving hydrographic conditions, water quality, ocean chemistry, HABs, and the associated impacts on marine habitats and marine life, from microbes to vertebrates.

And the collaborations using this data are only expanding.

“Every variable you can think of, we’re collecting,” says Enrique Montes, Ph.D., a CIMAS scientist and Director of AOML’s Ecosystems Assessment team.

Departing out of South Beach, Miami, onboard the R/V Walton Smith. The CTD (Conductivity, Temperature, Depth) instrument on the deck is deployed at reoccupied sites on the ship’s track to collect discrete water samples.

Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), nutrients, salinity, temperature, chlorophyll a, and dissolved oxygen profiles are amongst the list of water quality parameters the team measures at marked coordinates across depth – from Miami to the Florida Keys, to the west Florida shelf as far north as Tampa Bay. And all in seven days.

Departing out of Miami, these cruises aboard the R/V Walton Smith began in 1998 as hydrographic cruises to survey the physical features comprising South Florida waters from the Atlantic to the open Gulf of America. Since then, the scope of this effort has drastically expanded.

Bio-optical measurements – i.e. constituents in the water interacting with light – are used to detect freshwater discharge, phytoplankton species driving and supporting all marine ecosystems, and the particulate matter contributing to the biological carbon pump. These observations are also utilized to refine the interpretation of data collected by satellites, which enable a much broader view of the region.

R/V Walton Smith

Ian Smith (right) and Enrique Montes, Ph.D. (center) perform plankton net tows on the Walton Smith.

By sampling environmental DNA (eDNA) – the slough of genetic material shed by marine organisms into the environment – and using ‘Omics techniques at these designated sites, the team can identify the biodiversity present in a specific ecosystem from microbes to species of fish on a reef.

Doing this repeatedly on every cruise allows scientists to track major changes in biodiversity and species that can be used as indicators of ecosystem health.

At specific sites, the team conducts plankton productivity and grazing experiments to examine how different environmental conditions and the presence and biomass of different phytoplankton groups might affect the transfer of energy up the food web.

In November of last year, scientists observed a high abundance of Karenia brevis, a dinoflagellate that forms recurring harmful algal blooms in South Florida with widespread impacts. Blooms often extend from estuaries to offshore, and can sometimes be transported to other parts of Florida or even other states.

Plankton net tows and imaging combined with analysis of phytoplankton collected via the ship’s flow-through system allow the team to identify an array of planktonic species and map out the size and scale of harmful algal blooms while on the ship, which can aid in event response efforts.

“Between July and September last year, we found large diatom blooms along the west Florida shelf near areas of freshwater discharge,” explains Dr. Montes. “We started to see high counts of K. brevis in October after the passing of hurricanes Helene and Milton. “Long-term programs like SFER are key to understanding the impacts of episodic disturbances on Florida marine habitats”, indicates Dr. Kate Hubbard, lead of the harmful algal bloom (HAB) monitoring and research program of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Research Institute.

Traversing just outside Sarasota and Venice, Florida in November 2024, the team witnessed the impacts of high concentrations of K. brevis leading to miles of fish kills.

“This specific HAB produces brevetoxin that can lead to mass fish kills,” says Dr. Montes, “ HAB events often coincide with low-oxygen conditions or hypoxia, particularly at depth, further enhancing mortality but this process is still not well understood”

In collaboration with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission-Fish and Wildlife Research Institute (FWC-FWRI) team led by Katherine Hubbard, Ph.D., SFER surveys are aiding in augmenting our understanding of the distribution, drivers,and impacts of HABs across South Florida. To help share results with the public and managers of the impacts of red tide, data is posted via the FWC’s online red tide tracking tool used to alert the public of red tides – and the significant effects on human health – and for commercial fishers to strategize where they will have the most fishing success. These surveys also provide critical research observations to help understand more about why blooms vary in severity from year to year.

Continuously performing these cruises, scientists at AOML are establishing a comprehensive, long-term baseline of the conditions influencing key marine ecosystems – including three national parks and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. And the scope of this research is only expanding with new collaborations.

CIMAS Scientists Rob Bremer (left) and Tyler Christian (right) onboard Tatiana to conduct conduct research in the Halozone.

Last November, the team expanded sampling efforts at four of the existing transects in the Florida Keys into the halozone – the first 500 meters from the shoreline – under a newly-funded Environmental Protection Agency project.

Branching into shallower and more brackish waters with the small boat from the R/V Walton Smith, the R/V Tatiana, the team sampled microbes, nutrients, chlorophyll, environmental DNA (eDNA) and other water quality parameters.

“The idea is to connect those very nearshore measurements to what we observe offshore,” says Dr. Montes. “This allows us to understand how waters with poor quality conditions near the coastline reach more offshore waters bathing coral reefs.”

The sheer volume of data from these cruises is only increasing – and so are the projects they’re being used for.

As part of the Florida Regional Ecosystems Stressors Collaborative Assessment (FRESCA), researchers are developing high-resolution ecosystem models to assess the impacts of five key environmental stressors.

Given that South Florida’s ecosystems are impacted by a variety of environmental stressors – and none of them in isolation – this new project co-led by scientists at AOML, the University of Miami, the University of South Florida, and Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) seeks to investigate how multiple stressors impact specific regions – and how the combined effects of multiple stressors will impact essential ecosystems.

CIMAS Scientist Rachel Cohn logging data onboard the Walton Smith during a recent SFER Cruise

“Long-term monitoring projects, like these SFER cruises, are foundational to informing advanced ecological modeling,” says Brittany Troast, a CIMAS Senior Research Associate with AOML’s Ecosystem Assessment Team, “And they provide necessary baselines when addressing disturbances or extreme events in the system.”

In 2000, Congress authorized the largest watershed restoration effort within the United States – restoring the Everglades. That is how the scope of the SFER cruises first expanded beyond mapping the physical features.

Spanning over 35 years and encompassing 18,000 square miles across six counties, the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Project (CERP) seeks to restore the natural flow of water across the South Florida ecosystem – providing significant economic benefits for key fisheries, habitats and coastal communities.

But this requires understanding the current conditions across Biscayne Bay, the Florida Keys and the entire West Florida Shelf – and how they will be influenced by future restoration.

Led by AOML’s Ecosystem Assessment team, the data from these cruises are being used to establish ecosystem health indicators for CERP that will guide effective restoration efforts – spearheaded by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers – once that phase of the project begins.

The goals of these cruises under the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Program have only grown since CERPS’s initiation with new projects optimizing the longterm monitoring already being performed – demonstrating just how vital it is for this research to continue in the face of rising environmental threats.

The wide ranging applications of this long term monitoring project allows AOML and CIMAS scientists to be proactive rather than reactive–so when disturbances, management needs, or changes arise, we are well equipped with the current, best information to provide to partners and the public in South Florida.