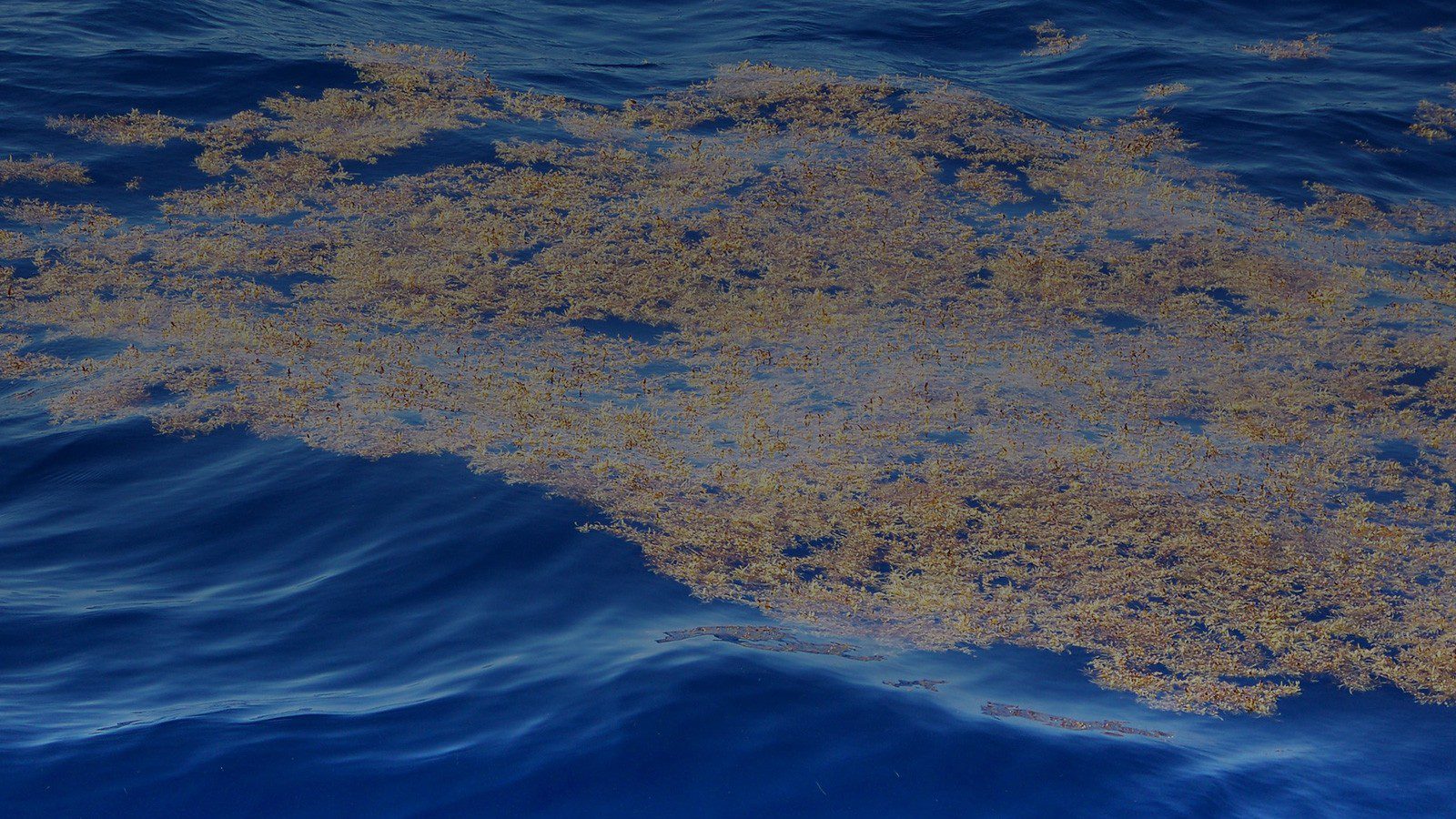

Since 2011, the coastlines of the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea have been plagued by extraordinary accumulations of a type of floating brown alga, commonly called “seaweed” and known as Sargassum. These alga float at the sea surface, where they can aggregate to form large mats in the open ocean.

Off the U.S. eastern seaboard (in the Sargasso Sea) and the Gulf of America, free-floating Sargassum has always been common. These alga provide an essential habitat, with food sources, nursery areas, and breeding grounds for fish, sea turtles, and birds. However, the increased abundance of Sargassum in the tropics since 2011, stretching from Africa to the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of America, has had adverse effects on the regions’ coastal ecosystems and local human communities.

The ways in which Sargassum has invaded the tropical Atlantic have been a mystery, but we may now have an answer. A new study in Progress in Oceanography, led by researchers at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML), identifies possible mechanisms and pathways by which Sargassum entered and flourished in the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean.

“We were particularly interested in understanding the origins of the tropical Atlantic’s Sargassum population and how it is being sustained. Its presence has caused severe socioeconomic impacts on local communities” said Libby Johns, AOML Oceanographer and lead author of the study.

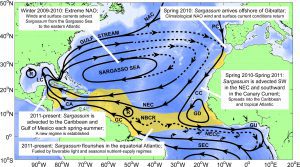

Researchers discovered that during the winter of 2009-2010, the winds that typically blow to the east, from the Americas to Europe, strengthened and shifted to the south. This shift in winds was very unusual and triggered a long-distance eastward dispersal of Sargassum, from the Sargasso Sea, toward the Iberian Peninsula in Europe and West Africa. After exiting the Sargasso Sea, the Sargassum drifted southward in the Canary Current and entered the tropics. Once in this new and favorable tropical Atlantic habitat, with ample sunlight, warm waters, and nutrient availability, the Sargassum flourished and has continued to grow.

Having established a new population, the Sargassum now aggregates almost every year in April-May in a massive windrow or “belt” north of the Equator, along the region where the trade winds converge. During the spring, the Sargassum follows this convergent region’s northward seasonal excursion. By June, the belt stretches across the entire central tropical Atlantic. Large portions of the algae are then transported to the Caribbean and Gulf of America via the North Equatorial and Caribbean current systems.

“Predicting the occurrence of Sargassum blooms will help us better understand their impacts on our ecosystems, and thereby improve our scientific advice in the management of our fisheries and protected species” said Cisco Werner, Chief Science Advisor, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service.

Out at sea, Sargassum is an important habitat, but as it accumulates close to the coastlines it can smother valuable corals, seagrass beds, and beaches. As it washes ashore the seaweed begins to decay, attracting flies and other insects. During its breakdown, Sargassum produces hydrogen sulfide gas which smells of rotten eggs, repelling beachgoers and affecting the tourist industry that depends on pristine ocean conditions.

This study offers new insight into the recent Sargassum events. Further studies, in collaboration with our international partners across the North Atlantic, Caribbean, and the Gulf of America, will be necessary to fully understand and improve predictions of the distribution and impacts of Sargassum outbreaks, and to develop actions to effectively mitigate the invasions.

This study was conducted in collaboration with researchers from the University of South Florida, the University of Miami Rosenstiel School for Marine and Atmospherics Studies, the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, private industry, and NOAA Fisheries.