On September 21, 1938, a hurricane moving at over 50 mph struck Long Island and raced over New England, bringing a storm surge and heavy rainfall. It would be remembered for generations as the “Long Island Express”.

The storm originated from a disturbance detected off Africa on Sept. 9th. It was tracked via ship reports as it made steady progress to the west-northwest over the next ten days. It also strengthened, and by the time it was about 200 miles east of the Bahamas, the Jacksonville Hurricane Warning Center was estimating its winds at 160 mph (260 km/hr). Jacksonville issued a hurricane warning for Florida.

But the storm began to turn northward and seemed to be recurving. The Jacksonville office changed the warnings from Florida to the Carolinas. By the evening of the 20th, the hurricane diminished slightly in strength and responsibility for tracking the storm was handed off to the U.S. Weather Bureau’s Washington office.

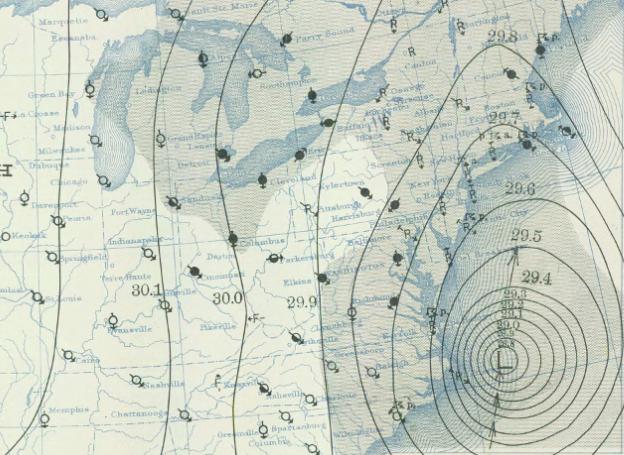

The next morning, it was 100 miles east of Cape Hatteras and had weakened further. But it had begun to interact with a frontal system to the west which was accelerating the hurricane’s forward motion to nearly 50 mph. The Washington forecasters had not fully grasped this hastening and were slow to post storm warnings for the Northeastern United States. Even then, they under-warned for the potential strength of the storm, only issuing gale warnings.

By the late afternoon of the 21st, the storm was rushing ashore on the eastern tip of Long Island and pushing a tremendous storm surge over Montauk, obliterating the tracks of the Long Island railway. As the hurricane dashed forward, it pushed the surge up Narragansett Bay into downtown Providence. The 13′ 8″ (417 cm) surge level exceeded the old record from the 1815 hurricane by 2′ 4″ (71 cm).

Even though the storm was moving quickly, it managed to dump heavy rainfall across the New England area. Up to 17″ (432 mm) of rain fell on parts of Connecticut. And winds throughout the area toppled both trees and church steeples and un-roofed homes. The hurricane caused over 600 direct deaths and US$300 million in damages.

The failure to adequately warn for the fast-moving storm spurred the Weather Bureau to adopt the air mass and polar front theories that had revolutionized European meteorological operations.

The hurricane had as great a cultural impact as a meteorological one since it hit not only a densely populated area, but home of the nation’s publishing industry and its artistic and intellectual center. Many novels, movies, and paintings were inspired by the disaster, and the storm remained a milestone for New Englanders for decades to come.