(NOAA)

On October 29, 2012, Extratropical Cyclone Sandy (dubbed Superstorm Sandy by the media) made landfall at Brigatine, New Jersey bringing a massive storm surge to New Jersey and New York. It was the costliest storm for that hurricane season and the second costliest in recorded history. It was also an extraordinary study in complex transitions between various dynamics in one storm.

Sandy began as a tropical disturbance which exited the African coast on Oct. 11th. However, wind shear across the tropical Atlantic prevented it from becoming organized until it reached the central Caribbean Sea by Oct. 22nd. There conditions improved and the convection organized into a tropical depression near Panama. As it drifted slowly northward the system quickly strengthened into a Tropical Storm and was given the name Sandy.

Over the next two days, Sandy gradually gained strength and continued its slow progress north-northeastward toward Jamaica. Just prior to hitting near Kingston, Air Force reconnaissance found hurricane-force winds and Sandy was upgraded. The hurricane raked the island with winds and heavy rains. Flash floods and landslides caused most of the US$100 million in damage on the island and the one Jamaican fatality directly attributed to Sandy.

The hurricane was little diminished by its passage over Jamaica and struck Santiago de Cuba seven hours later at even greater force. The eastern end of Cuba was ravaged by heavy winds and a 6 foot (2 m) storm surge. Eleven deaths and US$2 billion in damage were suffered as Sandy moved over the island.

(Craig McLean)

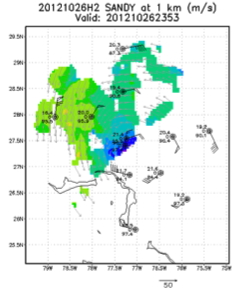

The Bahamas were next to be struck as Sandy moved northward and maintained Category-2 force winds. At this point NOAA42 began a series of seven Tail Doppler Radar missions that would continue over the next four days. Meanwhile, NOAA49 began its series of daily Synoptic Surveillance missions in an effort to resolve a disparity in various track models. Some of the models were forecasting Sandy to turn eastward, out to sea. However, others were indicating a westward turn toward the Mid-Atlantic states.

(NOAA)

In addition to the uncertainties in future track, Sandy was also reorganizing its structure. It was no longer fully a tropical cyclone but more of a hybrid system, partly tropical and party extratropical. The continuing NOAA42 flights documented this change as dry air intruded on the system and increased shear from a nearby trough made the circulation more asymmetric. But the core of Sandy began to regain some tropical characteristics while embedded in a larger baroclinic circulation.

(NOAA/AOML/HRD)

After the last TDR mission, Sandy began to make a northwestward turn and the various models converged on the same solution of a landfall on the New Jersey shore. Just two hours before its final landfall, the National Hurricane Center determined that Sandy had lost its tropical characteristics and was no longer officially a “hurricane”. This caused confusion among officials, the public, and the press about what Sandy was and how bad it would be. The press started using the term “Superstorm” to convey the danger inherent in the storm since the official term ‘“extratropical” did not register with most of the public.

Just before 8 PM on Oct. 29th, the center of Sandy crossed the Jersey shore. But long before this time the tremendously wide wind field was bringing heavy winds from New England to Virginia, torrential rains on the Delmarva peninsula, and funneling a storm surge along the Long Island shore and into New York City, flooding lower Manhattan and the subway system. Many people living along the shoreline had never experienced a direct tropical storm impact or had not suffered high storm surge during Irene’s impact the previous year. Numerous people tried to ride out the storm in their seaside residences, which led to many of the 71 direct deaths. The cost of the storm in the United States was an astounding US$71 billion.

The remnants of Sandy continue northward eventually affecting Canada before becoming incorporated into a frontal system. In the process, Sandy caused massive power outages and brought up to 35″ (900 mm) of snow to the Northeast. In total, 233 deaths were attributed to Sandy and in excess of US$75 billion in damage.

The data collected in Sandy will be studied for decades. Its complicated life history provided insights into how tropical cyclones transition to other forms of storm and interact with mid-latitude systems. Its transition from hurricane status prior to its New Jersey landfall prompted the National Hurricane Center to adopt the term “post-tropical cyclone” for future events to avoid the confusion that ensued in Sandy.

References

Evans, C., K. M. Wood, S. D. Aberson, H. M. Archambault, S. M. Milrad, L. F. Bosart, K. L. Corbosiero, C. A. Davis, J. R. Dias Pinto, J. Doyle, C. Fogarty, T. J. Galarneau Jr., C. M. Grams, K. S. Griffin, J. Gyakum, R. E. Hart, N. Kitabatake, H. S. Lentink, R. McTaggart-Cowan, W. Perrie, J. F. D. Quinting, C. A. Reynolds, M. Riemer, E. A. Ritchie, Y. Sun, and F. Zhang, 2017: The extratropical transition of tropical cyclones. Part I: Cyclone evolution and direct impacts. Mon. Wea. Rev., 145, 4317-4344.

Martinez, J., M. M. Bell, J. L. Vigh, and R. F. Rogers, 2017: Examination of tropical cyclone structure and intensification with the extended flight level dataset (FLIGHT+) from 1999 to 2012. Mon. Wea. Rev., in press.

Zhang, X., S. G. Gopalakrishnan, S. Trahan, T. S. Quirino, Q. Liu, Z. Zhang, G. Alaka, and V. Tallapragada, 2016: Representing multiple scales in the Hurricane Weather Research and Forecasting modeling system: Design of multiple sets of movable multilevel nesting and the basin-scale HWRF forecast application. Wea. Forecast., 31, 2019-2034.