(NOAA/WPC)

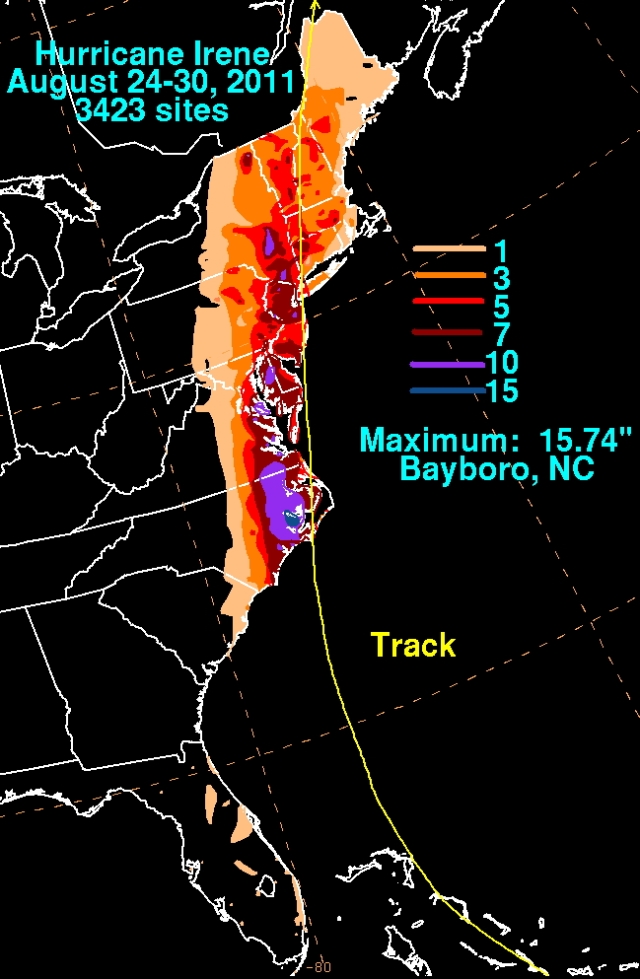

On August 28, 2011, Hurricane Irene made landfall on the Jersey shore. It brought devastating destruction to New England as it dumped torrential rains throughout the region.

Although Irene began as an African easterly wave, it wasn’t until it had crossed most of the Atlantic Ocean to be east of Dominica that it developed a circulation center and was named on Aug. 20th. It moved over the Leeward Islands and strengthened as it approached Puerto Rico. Despite interaction with the mountainous island, where it released copious rains, Irene attained hurricane strength shortly after reaching the sea again. Nearly a half of a billion US dollars’ worth of damage was inflicted in its passage.

As Irene approached the Turks and Caicos islands, the storm reached Category 2 status and NOAA began a series of research missions into the storm. While NOAA 49 began Synoptic Surveillance flights around the storm in attempt to improve the track model forecasts, NOAA 42 flew Tail Doppler Radar experiments, gathering Doppler radar measurements of the winds of the inner core of the storm that were ingested into experimental intensity forecast models.

Irene spent the next two days roaring through the Bahamas as a major hurricane, inflicting US$40 million in damage from wind and heavy rain. The hurricane then turned northward and weakened significantly as it approached the Carolinas. It made landfall at Cape Lookout on Aug. 27th as a Category 1 hurricane. It turned slightly eastward and skimmed along the eastern coast of the United States, making landfalls in New Jersey and Long Island as a tropical storm. It moved inland in New England, dumping tropical downpours as it went. Rivers became torrents and swept away many historic covered bridges in the region.

Overall, Irene did US$16.5 billion in damage and resulted in 49 direct deaths, the majority of the damage and casualties occurring in the United States.

Papers written by HRD scientsts using Irene data:

Aberson, S. D., 2014: A climatological baseline for assessing the skill of tropical cyclone phase forecasts. Wea. Forecasting, 29, 122-129.

Aberson, S. D., A. Aksoy, K. J. Sellwood, T. Vukicevic, and X. Zhang, 2015: Assimilation of high-resolution tropical cyclone observations with an Ensemble Kalman Filter using HEDAS: Evaluation of 2008-11 HWRF Forecasts. Mon. Wea. Rev., 143, 511-523.

Giammanco, I. M., J. L. Schroeder, and M. D. Powell, 2013: GPS dropwindsonde and WSR-88D observations of tropical cyclone vertical wind profiles and their characteristics. Wea. Forecasting, 28, 77-99.

Rogers, R, and co-authors, 2013: NOAA’s Hurricane Intensity Forecasting Experiment: A progress report. Bull. Amer. Met. Soc., 94, 859-882.

Walsh, E. J., I. PopStefanija, S. Y. Matrosov, J. Zhang, E. Uhlhorn, and B. Klotz, 2014: Airborne rain-rate measurements with a Wide-Swath Radar Altimeter. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol., 31, 860-875.

Zhang, J. A., D. S. Nolan, R. F. Rogers, and V. Tallapragada, 2015: Evaluating the impact of improvements in the boundary layer parameterization on hurricane intensity and structure forecasts in HWRF. Mon. Wea. Rev., 143, 3136-315.