Amenazas para los arrecifes de coral

Identificar y afrontar las amenazas a las comunidades de arrecifes

SALTO A LA OLA DE CALOR MARINA

O DESPLÁCESE PARA SABER MÁS

Qué entendemos por "amenazas

Los arrecifes de coral se enfrentan a diversos factores de estrés antropogénicos y medioambientales, desde el calentamiento de las temperaturas oceánicas y los episodios de blanqueamiento hasta las enfermedades provocadas por el cambio climático y el aumento de la actividad humana, lo que conduce a la degradación, la pérdida de biodiversidad y la disminución de los beneficios ecosistémicos que proporcionan los arrecifes.

Antes de poder ofrecer soluciones viables y realistas, debemos identificar y abordar los factores de estrés que afectan de forma más inmediata a las comunidades de arrecifes de coral, desde el calentamiento de la temperatura de la superficie del mar y los fenómenos de blanqueamiento hasta las enfermedades. Esta página sirve de herramienta para mantenerle al día e informado sobre las amenazas actuales a estos ecosistemas naturales.

El coral cuerno de alce (Acropora palmata) es un coral esencial para la construcción de arrecifes en todo el Caribe, y actualmente se encuentra en peligro crítico (estatus UICN) debido al calentamiento de los océanos.

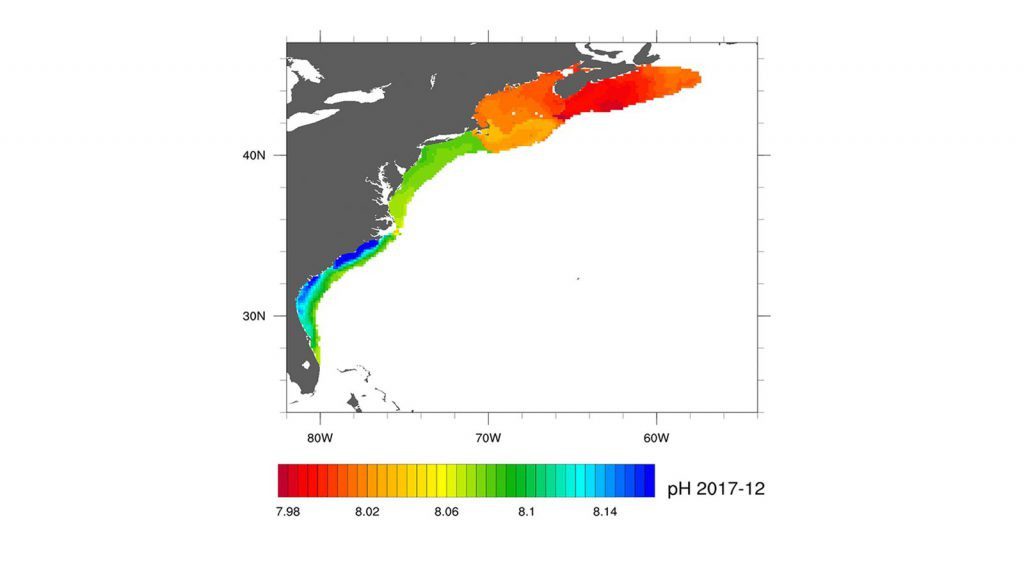

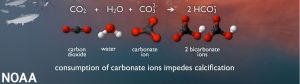

Acidificación de los océanos

A medida que los océanos se calientan, son capaces de absorber y almacenar mayores concentraciones de dióxido de carbono (CO2), lo que tiene graves efectos negativos en los ecosistemas de arrecifes y otros entornos marinos de todo el mundo: Acidificación oceánica (AO). Desde el punto de vista químico, un aumento del CO2 absorbido por el océano provoca un aumento de los iones de hidrógeno (H+) en el océano a través de una serie de reacciones químicas, lo que hace que los océanos se vuelvan más ácidos. Este aumento de los iones de hidrógeno amenaza los arrecifes de coral, ya que se unen al carbonato, una molécula esencial que los corales necesitan para construir su duro esqueleto interno (compuesto de carbonato cálcico, CaCO3). Con menos iones de carbonato disponibles, los corales y otros organismos, incluidas las ostras y los mariscos, no pueden mantener y construir las estructuras duras que necesitan para vivir.

Los efectos de la acidificación de los océanos sobre los arrecifes de coral se ven así amplificados por el aumento de las emisiones de carbono a la atmósfera. Identificar cómo persisten los corales en respuesta a este factor de estrés medioambiental es crucial para comprender el futuro de los ecosistemas de arrecifes de coral. Los científicos del AOML siguen investigación, incluido un nuevo marco de seguimiento que contribuirá a los esfuerzos de recuperación y restauración.

Decoloración del coral

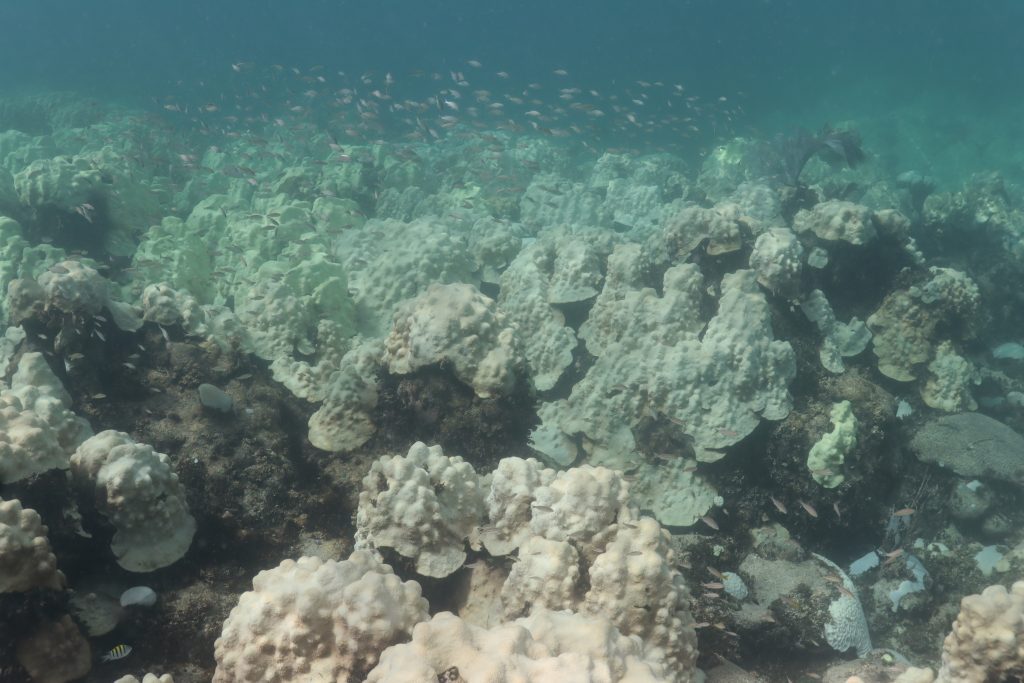

El blanqueamiento de los corales se produce cuando los corales sufren estrés físico debido a cambios extremos de temperatura, luz o concentración de nutrientes en su hábitat circundante, y expulsan las algas fotosintéticas que se encuentran en sus tejidos, lo que los vuelve de un blanco pálido y los deja vulnerables a la mortalidad. Sin embargo, el blanqueamiento no significa que los corales mueran inmediatamente, y pueden recuperarse de un episodio de blanqueamiento.

Estas algas fotosintéticas son a la vez la principal fuente de alimento de los corales (producen carbohidratos orgánicos que el coral necesita para sobrevivir) y les dan su vibrante coloración, explicando así por qué se vuelven de un blanco pálido cuando se expulsa el alga. Cuando se produce el blanqueamiento, los corales no pueden volver a albergar sus algas fotosintéticas hasta que se reduce el estrés físico (altas temperaturas de la superficie del mar, menor penetración de la luz en el ecosistema marino, etc.), y cuanto más tiempo persiste el estrés físico, más probabilidades tienen los corales de sufrir mortalidad.

Para ver cómo es el blanqueamiento, haga clic aquí.

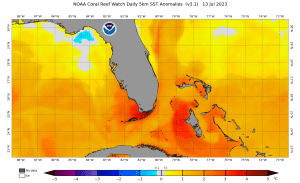

Olas de calor marinas

A ola de calor marina es cuando la temperatura del océano es extremadamente cálida en relación con lo que suele considerarse "normal", o por encima del percentil 90 durante al menos 5 días, pero algunas pueden durar meses. La prolongada ola de calor marina de 2023 en el Océano Atlántico, el Golfo de México y el Mar Caribe puede tener repercusiones negativas en los ecosistemas marinos, concretamente en el blanqueamiento de los corales. Para saber más, consulte aquí.

Enfermedades de los corales

Los corales son muy susceptibles a diversas enfermedades cuya frecuencia ha aumentado en las últimas décadas. La enfermedad de la banda blanca amenaza principalmente a Acropora cervicornis (cuerno de ciervo) y Acropora palmata (cuerno de alce), dos especies incluidas en la ESA que son clave para los esfuerzos de restauración en Florida y el Caribe. Cada vez preocupa más la rápida propagación de la Enfermedad de pérdida de tejido del coral pétreo (SCTLD) que se observó por primera vez en Virginia Key en 2014 y se ha expandido por todo el Caribe.

El Programa Coral del AOML está a la vanguardia de un esfuerzo esfuerzo multiinstitucional que se esfuerza por abordar y vigilar estas enfermedades con una investigación continua destinada a encontrar soluciones que mitiguen los efectos de las enfermedades en los ecosistemas esenciales de los arrecifes. Para saber más sobre nuestra investigación de las enfermedades de los corales haga clic aquí.

Dragado

Desenterramiento de escombros y resuspensión de sedimentos del fondo de los medios marinos durante el dragado es uno de los principales factores de estrés para los corales. El dragado suele realizarse para ensanchar o profundizar los canales de navegación en masas de agua utilizadas para el transporte marítimo y la navegación de recreo. A medida que los buques aumentan de tamaño para transportar mayores cargas, los canales deben hacerse más profundos y anchos.

¿Cómo afecta esto a los corales?

Si no se hace con cuidado, el dragado puede remover los sedimentos y aumentar la turbidez. la turbidez que atenúa la cantidad de luz que necesitan los simbiontes fotosintéticos que viven en el tejido blando de los corales. Además, las altas tasas de sedimentación pueden provocar la mortalidad de los corales al enterrar las colonias y disminuir la capacidad de las larvas de coral para asentarse y sobrevivir en la zona afectada. Cuando el sedimento marino se resuspende, también puede transportar bacterias patógenas que pueden desencadenar brotes de enfermedades coralinas.

¿Qué se está haciendo?

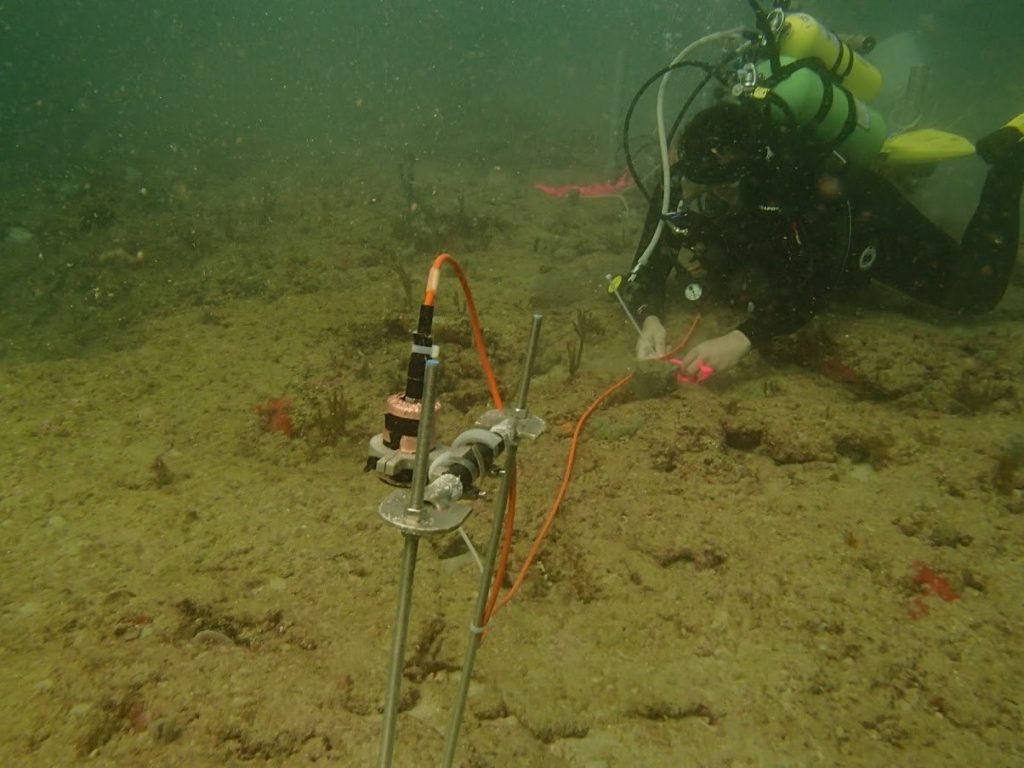

Los científicos del AOML trabajan en colaboración con el Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército (ACE) para desarrollar el Sintetizador de Información Medioambiental para Sistemas Expertos (EISES)un sistema puntero de control de la calidad del agua y la turbidez que servirá de base para la gestión de las actividades de dragado en Port Everglades de Ft Lauderdale, en Florida. El objetivo es mitigar los efectos del dragado en los ecosistemas bentónicos cuando comience la ampliación de Port Everglades en 2027. La realización de pruebas y la recopilación de datos antes del inicio de las operaciones de dragado son esenciales para establecer las condiciones de referencia de la turbidez, la calidad del agua y otros parámetros ambientales en los alrededores, a fin de distinguir entre las perturbaciones causadas por procesos naturales (por ejemplo, vientos fuertes y corrientes intensas) y las provocadas por el dragado.

El EISES está instalando múltiples paquetes de sensores en el fondo marino y cerca de la superficie que transmiten datos en tiempo real. Las boyas de superficie también recogen variables meteorológicas como la velocidad y dirección del viento, la temperatura, las precipitaciones, etc. Combinando estos conjuntos de datos, el EISES activará alertas tempranas cuando se detecten perturbaciones atribuidas al dragado para informar a la administración de cuándo deben reducirse o detenerse temporalmente las actividades de dragado para aliviar la presión sobre los ecosistemas marinos.

Ola de calor marina Preguntas frecuentes

Las olas de calor marinas son fenómenos anómalos de calentamiento por encima del percentil 90. En sentido práctico, significa que ocurren un 10% de las veces en relación con los registros a largo plazo, normalmente medias de 30 años. En sentido práctico, significa que se producen el 10% de las veces en relación con los registros a largo plazo, normalmente medias de 30 años. A escala mundial, se producen entre 0 y 5 veces al año, con una duración de entre 5 y 40 días.

We monitor ocean surface temperatures from space and can see extremes develop in real time. Several factors may cause MHWs in the ocean, and these mechanisms influence the timescales of the predictions of these events. On top of all is global warming, which has already added more than 1 deg Celsius to the temperature above pre-industrial levels, It is projected to rise between 1.5 to 4C above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

Every marine heatwave is significant, by definition. Ocean temperatures in the Summer of 2023 (the most recent marine heatwave) were extremely warm relative to what we typically consider to be “normal”. Among historical marine heatwave conditions, the event of Summer 2023 was on the upper end of “average.”

The last time there was a marine heatwave of that magnitude that encompassed this much of the Gulf of Mexico was in 2020.

Water temperatures throughout the Gulf of Mexico and in the Caribbean Sea were anywhere from 1-2.5˚C (~2-4.5˚F) warmer than normal in July and early August of 2023. Temperature anomalies like this aren’t unprecedented, but they are concerning while in the thick of the Atlantic hurricane season (June – November) with the tropical North Atlantic already warm. Developing storms that pass into the region during a marine heatwave or with above average sea surface temperatures can be fueled by the warm waters as a result. Additionally, over time it will impact the different species of animals that call the ocean home.

The Gulf of Mexico marine heatwave began around November or December of 2022.

Nuestras previsiones experimentales de olas de calor marinas indican una probabilidad del 70-80% de que persistan las temperaturas oceánicas extremas en el sur del Golfo de México y el Caribe hasta octubre de 2023. Dicho esto, nuestra capacidad histórica de previsión en esta región, con una antelación de 3,5 meses, es menor (aunque sigue siendo mejor que las conjeturas aleatorias).

Exposure to extreme temperature for long periods of time causes a breakdown in the relationship between coral and the algae that lives inside of them. The coral is left pale or white, i.e., bleached. The lack of food from the algae can lead to the death of the coral, subsequent erosion of the habitat, and ultimately a loss of the ecosystem services that we rely on including fishing and food, storm protection, tourism, and biodiversity. We are seeing instances of coral bleaching in the Miami area. Severe bleaching and significant mortality is also likely if the marine heatwave persists.

When corals are stressed by changes in conditions, such as extreme temperatures or reduced light penetration, they may expel the symbiotic algae living in their tissues, causing them to turn completely white in a process known as bleaching. Without the algae, they lose their major source of food and can become weak, potentially leading to death. However, if the conditions return to within optimal range for the corals (i.e. sea surface temperatures returning to average range), then the coral can become host again to the symbiotic algae and recover from the bleaching event.

Para saber más sobre el blanqueamiento del coral: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coral_bleach.html

Cuando un coral se blanquea, no está muerto. Los corales pueden sobrevivir a una decoloración si las aguas se enfrían y otras fuentes de nutrición están disponiblespero están sometidos a más estrés y y, en última instancia a la mortalidad. El aumento de las olas de calor marinas puede causar un aumento de la mortalidad de los corales en los arrecifes de coral y dañar los servicios ecosistémicos. Sin embargo, con la ayuda de la previsión de olas de calor marinas, podemos anticipar los aumentos de temperatura y monitorizar los arrecifes de coral para conocer mejor sus amenazas y cómo podemos ayudar a mantener los ecosistemas marinos.

Para saber más sobre la previsión de ola de calor marina: https://psl.noaa.gov/marine-heatwaves/

Para los corales, la temperatura es importante, pero también lo es el tiempo que los corales están sometidos a estrés por el calor. Cuanto más tiempo persista este estrés, más probabilidades tendrán los corales de blanquearse. La decoloración no siempre conduce a la muerte. Pero, de nuevo, si no hay alivio del calor, los corales no tienen tiempo de recuperarse del estrés y acaban muriendo. Los corales son el alimento y el hábitat de otros organismos marinos, y si los corales mueren, esto tiene un efecto en cascada sobre el resto de la vida que sustenta el arrecife.

Hay más olas de calor marinas aisladas frente a la costa noreste de EE.UU., a lo largo de la corriente del Golfo. También hemos estado observando una gran ola de calor marina en el Pacífico nororiental (en el Golfo de Alaska) que ha estado en alta mar durante los últimos meses. Se teme que se extienda a lo largo de la costa oeste de Estados Unidos a medida que se desarrolle el actual fenómeno de El Niño.

Observaciones sobre la decoloración

(enero de 2023 - julio de 2023)

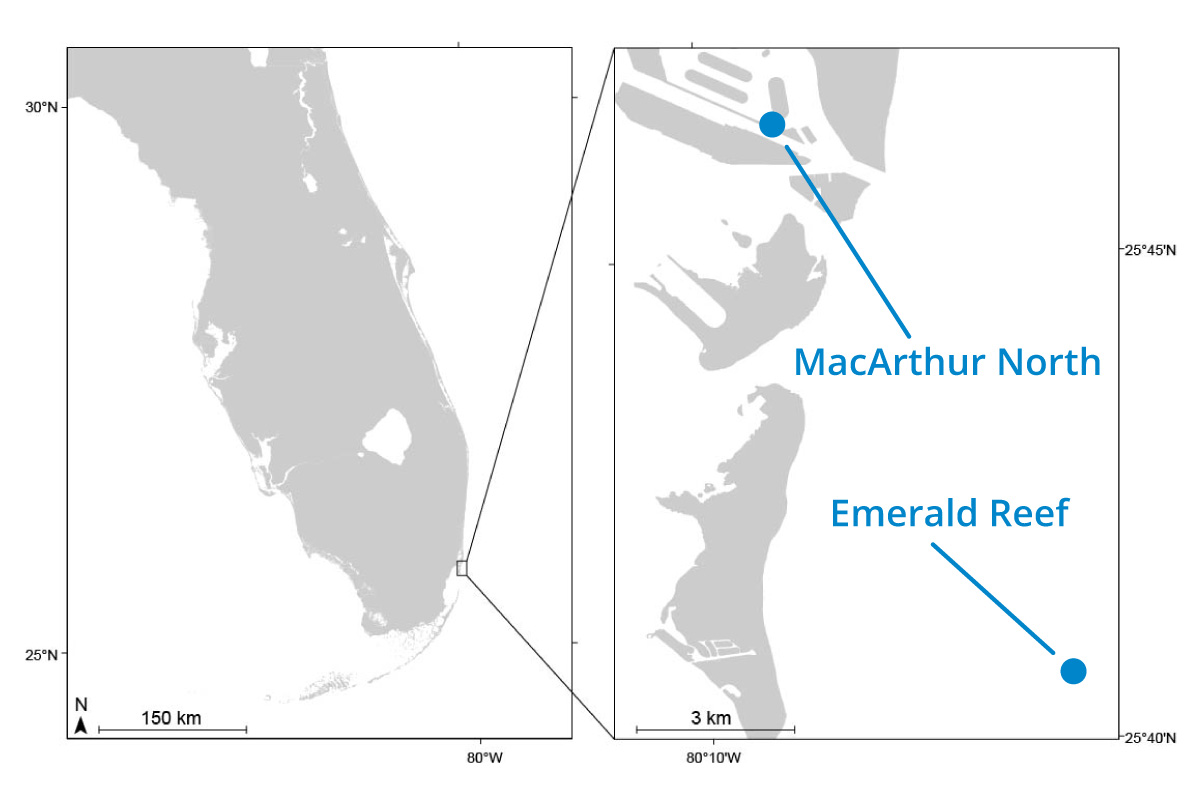

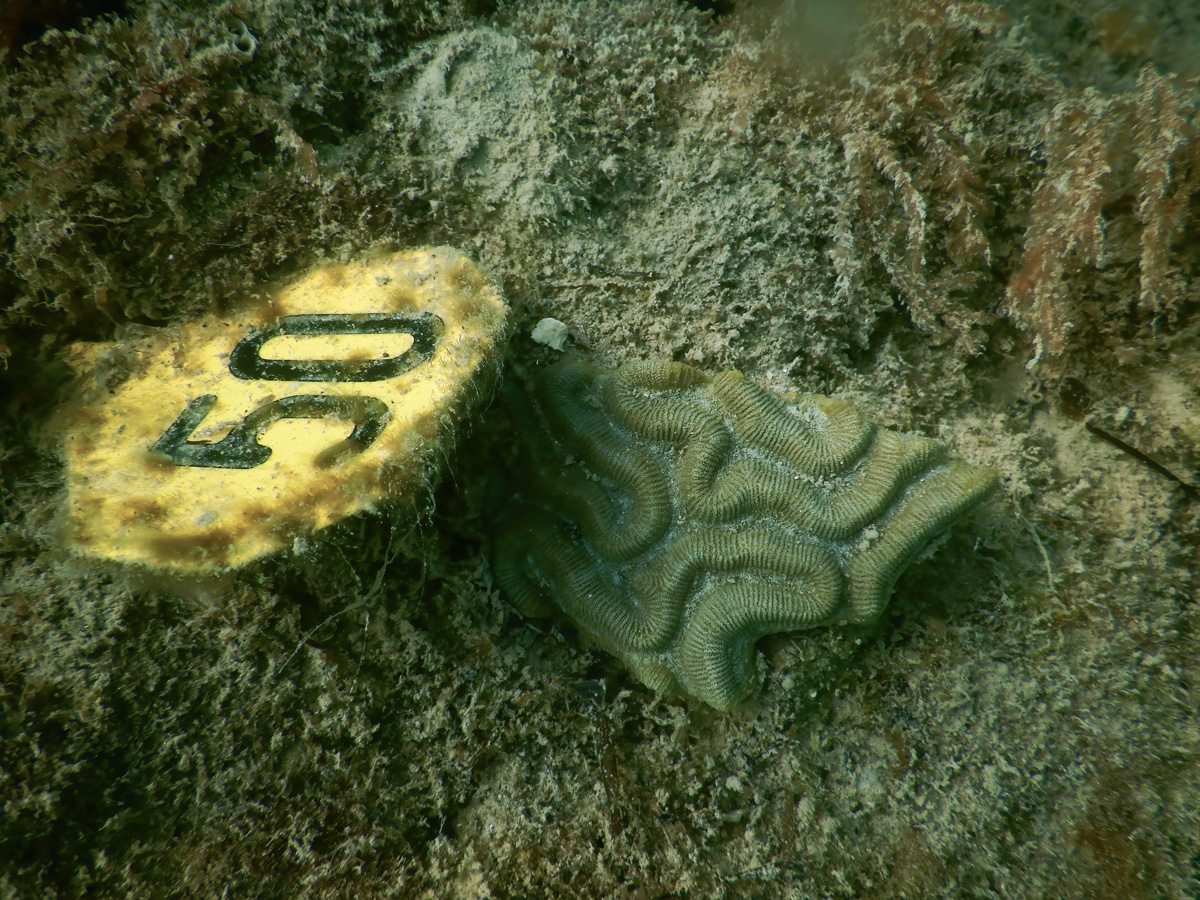

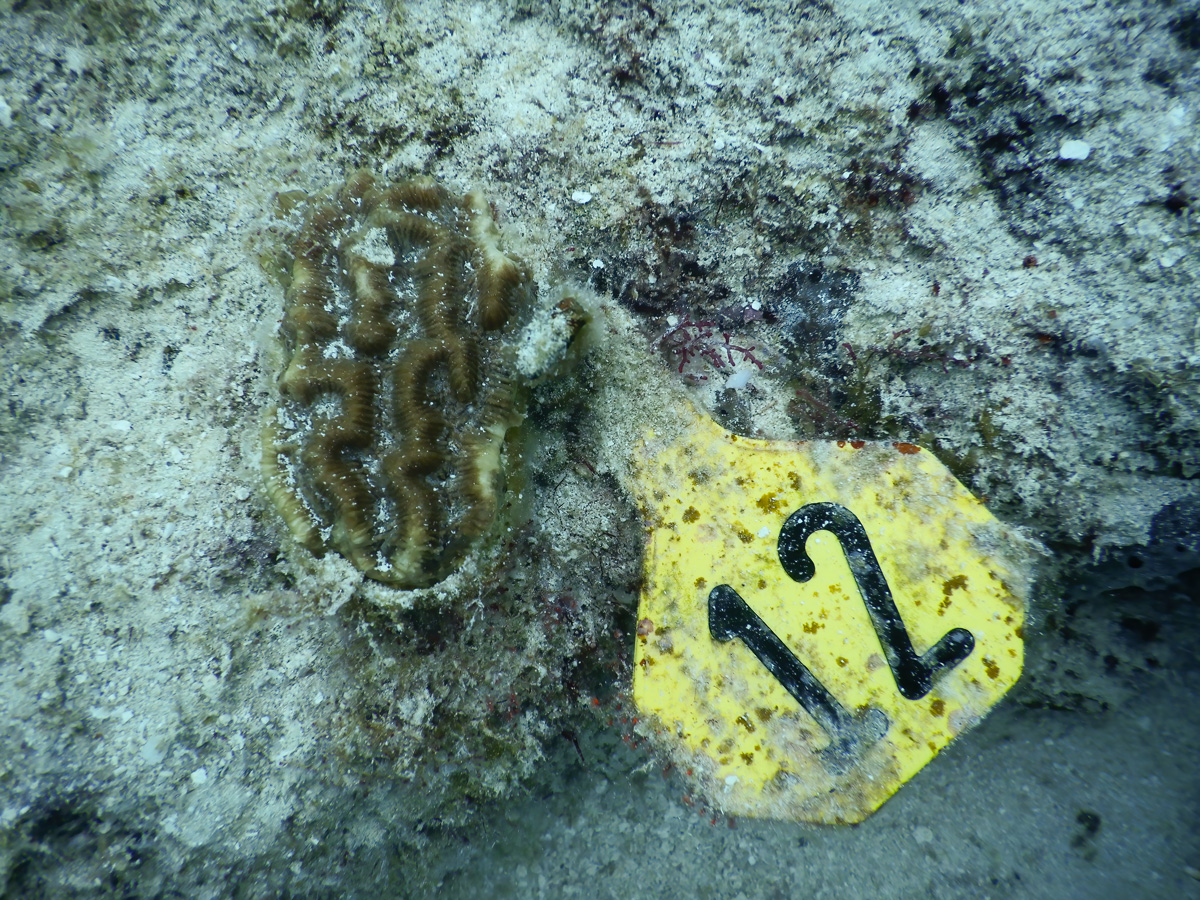

A continuación encontrará ejemplos de blanqueamiento en corales trasplantados experimentalmente en lugares de seguimiento e investigación a largo plazo por científicos del Programa Coral del AOML, la Universidad de Miami y el Instituto Cooperativo de Estudios Marinos y Atmosféricos debido a la ola de calor marina de 2023.

MacArthur Norte

11 de julio de 2023

11 de julio de 2023 26 de enero de 2023

26 de enero de 2023 11 de julio de 2023

11 de julio de 2023 26 de enero de 2023

26 de enero de 2023 11 de julio de 2023

11 de julio de 2023 26 de enero de 2023

26 de enero de 2023 11 de julio de 2023

11 de julio de 2023 26 de enero de 2023

26 de enero de 2023Arrecife Esmeralda

11 de julio de 2023

11 de julio de 2023 26 de enero de 2023

26 de enero de 2023 11 de julio de 2023

11 de julio de 2023 26 de enero de 2023

26 de enero de 2023 11 de julio de 2023

11 de julio de 2023 26 de enero de 2023

26 de enero de 2023 11 de julio de 2023

11 de julio de 2023 26 de enero de 2023

26 de enero de 2023