Hurricane Harvey brought up to 5 feet of rainfall to Texas and Louisiana in just a few days in 2017. The strongest rainfall typically happens near the center (eye) of a hurricane. Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall was unusually located far away from the eye. These unusual events make it difficult for forecast models to correctly predict rainfall when hurricanes and tropical storms make landfall. To understand how forecast models perform during such a rare event, this study tested two versions of NOAA’s hurricane model, the Hurricane Weather Research and Forecasting (HWRF) model.

Forecast models need to know what is happening now (what we call initial conditions) to forecast the future. This requires observations, but we cannot measure everything everywhere, and measurements are not always perfectly accurate. We therefore can have different initial conditions for the same observations. To account for this, we have run the HWRF model 20 times with different initial conditions (what we call an ensemble) to discover which versions most accurately forecast the rainfall and why.

- Conclusions:

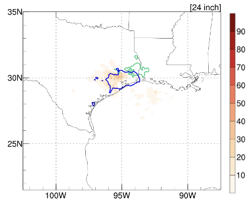

The HWRF model can predict the realistic total rainfall and maximum rainfall of Hurricane Harvey (Fig. 1).

The 20-run HWRF ensemble can forecast the locations of heaviest rainfall five days before the event (Fig. 2).

The HWRF model is an effective rainfall forecasting tool, which may be useful for real-time hurricane prediction, flood forecasting, or disaster management.

The methods to evaluate the model reported here will be very useful when applied to other models and storms.

You can access the full article at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4433/11/6/666.

For more information, contact Erica Rule, AOML Communications Director, at erica.rule@noaa.gov.