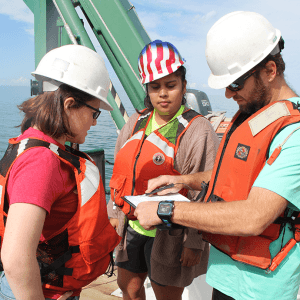

In August 2018, a team of biological oceanographers and ecologists set sail on the R/V Walton Smith to sample the waters of Biscayne Bay & Florida Bay. AOML has conducted regular interdisciplinary observations of south Florida coastal waters since the early 1990’s. We spoke with Chris Keble, the lead scientist for AOML’s South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Research project, to learn more.

What is the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Research project?

What is the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Research project?

The South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Research project (SFER) is part of a larger initiative to restore south Florida’s ecosystems. The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) was authorized by Congress in 2000 to “restore, preserve, and protect the south Florida ecosystem while providing for other water-related needs of the region, including water supply and flood protection.” It focuses on restoring the quality, quantity, timing, and distribution of freshwater to and from the Everglades. AOML supports this effort by researching how coastal ecosystems will likely be affected by Everglades restoration.

How does the everglades restoration project relate to our marine ecosystems?

Changing the quality, quantity, timing and distribution of freshwater runoff to south Florida’s bays and estuaries will affect local marine life. Our long-term study monitors and researches key indicators of the coastal ecosystem to improve our understanding and predictions of the coastal ecosystem response to restoration as a whole as well as to individual restoration projects.

The coastal ecosystems of south Florida are a major economic driver that needs to be considered and evaluated in all restoration decisions. The SFER accomplishes this by continually collecting and analyzing indicator data from our stations located throughout south Florida’s coastal ecosystem from Miami through the Keys and up to Naples. The data we collect is freely available for download on our website. We collaborate with the Southeast Fisheries Science Center, academic partners, the South Florida Water Management District, the National Park Service and the US Army Corps of Engineers to produce indicator assessments and predictive models that are used to make policy decisions.

What is the advantage to continually collecting data for water quality and other ecosystem indicators?

The main advantage is that water quality is highly variable and you do not see significant and important trends from only a single year, or even multiple years of data. In areas where we are observing water quality degradation, such as Biscayne Bay, these long-term trends require more than 10-years of data collection before they are statistically significant. A long-term dataset is essential to detect long-term trends in water quality that warrant action. Long-term datasets also allow us to identify the different factors that affect water quality. For example, we have evidence that Biscayne Bay water quality has been declining over the past 20 years. We examined the spatial distribution of these trends to determine that the degradation is being driven by the freshwater runoff entering the Bay from the Miami watershed.

The other advantage of long-term datasets is that it allows us to detect regime shifts, slowly degrading changes that are difficult to notice because they occur subtly over time. Once an ecosystem is observed and described, a baseline assessment of the overall quality is established. Long-term change invites a redefinition of everyday conditions, or a shift in the baseline. As an example, some areas of the coastal ecosystem have been subject to significant algal blooms, due to human activities such as the road construction in 2005 along US-1 entering the Florida Keys. This area experienced a multi-year algal bloom that appeared to have died back by 2009. However, 10-years later this area had still not returned to baseline levels for key water quality indicators. Long-term observations show that the baseline water quality has shifted and now is less resilient to future disturbances.

We are likely seeing similar disturbances now with the massive algal blooms in the Port St. Lucie and Charlotte Harbor areas due to the runoff. It can be difficult for an ecosystem that has had this level of disturbance to go back to the way it was. Long-term monitoring allows us to determine when we might be approaching tipping points that increases the likelihood, intensity, and duration of these major ecosystem disruptions before they occur and are either difficult or impossible to reverse.

What kind of variables do you measure as indicators of water quality?

South Florida is an oligotrophic system, which means it’s lower in nutrients. That’s beneficial for water quality and clarity. Once nutrients are added to the water the phytoplankton quickly take them up and increase in biomass. We use chlorophyll a, a proxy for phytoplankton biomass, as our primary indicator of water quality. This indicator can then be linked back to the nutrient flux.

We also measure nutrients, temperature and salinity. At specific sites, we measure primary productivity, grazing rates, zooplankton biomass. We have partnered with the Marine Biodiversity Observing Network (MBON), led by the University of South Florida, to collect samples of eDNA (environmental DNA) in the water column and near the benthic habitat. It’s a new technique where we measure the genetic signatures of everything from whales to specific phytoplankton to humans. This sampling uses DNA to tell us what organisms are in and around the water bodies we’re testing.

What are some of the challenges faced by the ecosystems of South Florida due to the declining water quality?

Hypersalinity is a huge problem. It occurs when freshwater runoff has been decreased to such a degree that it can double typical ocean salinities. Hypersalinity has caused massive habitat destruction with seagrass die-offs in Florida Bay. These die-offs have resulted in decreased abundances of many economically valuable sportfish.

How does this research benefit the community here in south Florida?

Restoring the natural flow and quality of water to the coastal ecosystems of south Florida through Everglades restoration can provide huge benefits, including to many local fishery populations. South Florida’s nearshore coastal ecosystems are key nursery habitats for many fish species and thus improving the health of these ecosystems will improve fish populations. The coastal ecosystems of south Florida are a huge economic driver.

People live and vacation here because they like to enjoy our beaches, and fish, dive, and boat in our waters. We need good water quality and good habitat to ensure these valuable activities can continue. We need only look at the current condition in the area around Ft. Myers on the southwest coast of Florida to see how damaging our coastal ecosystems can damage our economy.

Originally Published August 3rd, 2018 by Kristina Kiest