In August 2018, a team of biological oceanographers and ecologists set sail on the R/V Walton Smith to sample the waters of Biscayne Bay & Florida Bay. AOML has conducted regular interdisciplinary observations of south Florida coastal waters since the early 1990’s. We spoke with Chris Keble, the lead scientist for AOML’s South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Research project, to learn more.

AOML scientists part of team sampling water quality of extreme high tide floodwaters on Miami Beach

The colloquial term ‘king tides’, referring to the highest astronomical tides of the year, is now part of most Miami Beach residents and city managers’ vocabulary. Exacerbated by rising seas, these seasonal tides can add up to 12 inches of water to the average high tide, threatening the urbanized landscape of Miami Beach. During these events, AOML’s Microbiology Team is on the scene to investigate these tidal waters as they rise and recede. The microbiologists are part of a research consortium for sea level rise and climate change, led by Florida International University’s Southeast Environmental Research Center. The research effort focuses on collecting samples and monitoring water quality at locations along the Biscayne Bay watershed where the City of Miami Beach has installed pumps to actively push these super-tidal floodwaters back into the bay.

Because Miami Beach now regularly floods during super-tidal events or severe storms, it is important to understand how such coastal inundation events may cause land-based sources of pollution to enter the marine environment and how this pollution may impact both the ecosystem and human health.

“We don’t really know what comes from brackish water tidal floods in a built environment like Miami Beach, where water can spill over roads, yards, parking lots, and commercial sites” said AOML’s Dr. Chris Sinigalliano. “We have not yet measured how such tidal floodwater is similar or different to regular stormwater in the kinds of contaminants it accumulates and the potential risks associated with it.”

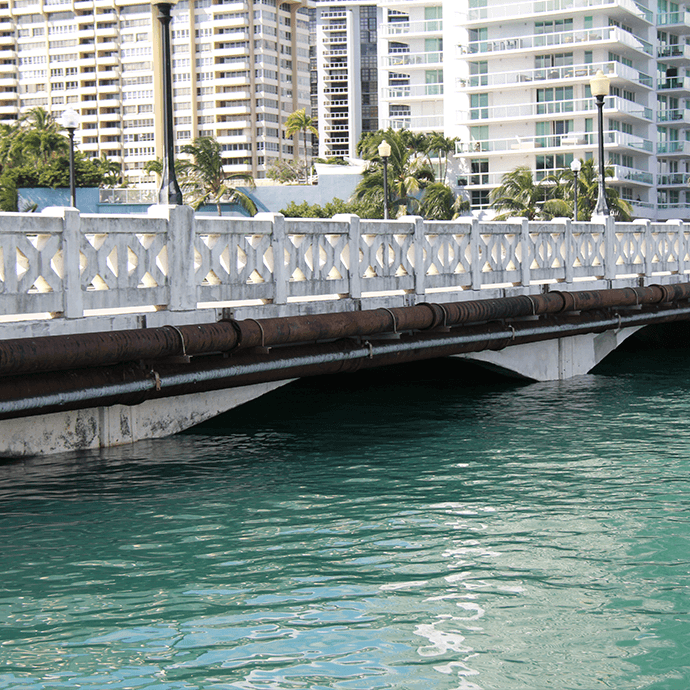

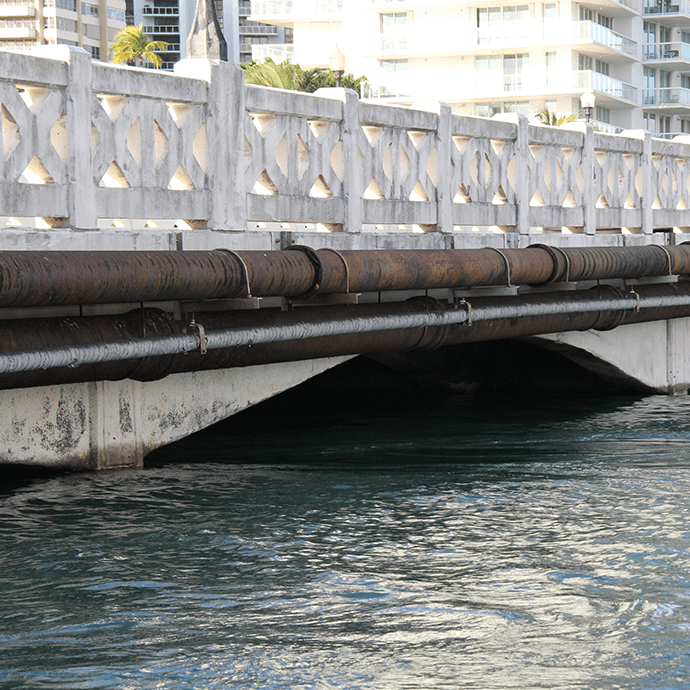

Researchers participating in this sampling effort continuously monitor and collect water samples over a 5-hour period near city pumps and storm drains where floodwaters re-enter Biscyane Bay. Onshore sampling sites include Maurice Gibb Memorial Park, 14th Street, and 27th Street at Indian Creek Drive. Samples are also collected by boat along canals and waterways that feed into the bay. During sampling, physical water properties such as temperature, salinity, pH, turbidity, and dissolved oxygen content are also measured.

The extent of flooding in the city during the king tides varies from year to year, especially around the area of Gibbs Memorial Park, due to Miami Beach’s pumping efforts. As the tidal waters recede, the discharges from the area of 14th Street generate noticeable plumes of turbid water in the bay, which scientists sample every hour.

The samples collected are brought back to the lab, where scientists prepare for hours of filtration and examination. FIU will test for a wide array of nutrients and biogeochemical markers while AOML tests for a variety of bacterial contamination markers to characterize the microbial water quality of the samples.

AOML also helps develop and validate molecular genetic techniques for analyzing the sources of various bacterial contaminants, a process known as ‘Molecular Microbial Source Tracking’. This analysis will help scientists, managers, and stakeholders understand what types of microbial pollutants exist in the tidal floodwaters and the possible environmental impacts of pumping this water back into the bay. Overall, AOML’s contributions to the king tide sampling effort include field sampling, analytical detection, measurement of microbial contaminants, including specific fecal-indicating bacteria, and identification of their potential sources using the Molecular Microbial Source Tracking method.

AOML scientists will also measure live enterococci (the fecal bacteria used for regulatory water quality monitoring of marine bathing waters) and quantify the abundance of specific source tracking bacteria. These source-tracking methods can determine the animal source the fecal bacteria originated from, including human, dog, birds, cows, and pigs.

Knowing the potential source of contamination provides actionable ‘Environmental Intelligence’ that can inform managers as they address contamination problems. Sewage and septic contamination is a human marker, terrestrial runoff can be linked to a canine marker, and agricultural waste contamination is linked to pig, cattle, and/or horse markers. Bird markers can also be detected and can indicate how much fecal contamination may be coming from seabirds and waterfowl.

FIU’s Southeast Environmental Research Center is leading the floodwater-sampling project and has provided the primary funding. This relatively small-scale pilot study leverages FIU’s partnerships with NOAA-AOML, the University of Miami, and Nova Southeastern University.

The analytical results from all participating laboratories will take several months to compile. A summary of the results will be made publicly available on FIU and AOML’s websites in order to inform stakeholders and interested parties.

The collective water quality information gathered from the king tide floodwaters on Miami Beach will be integrated across the multi-institutional research team. Results could further the understanding of the environmental impacts from tidal flooding of urban coastal landscapes and improve understanding of current and future impacts of sea level rise.