New research provides early warning of ocean acidification effects

Coral-Dominated State

Coral-Dominated State Algal-Dominated State

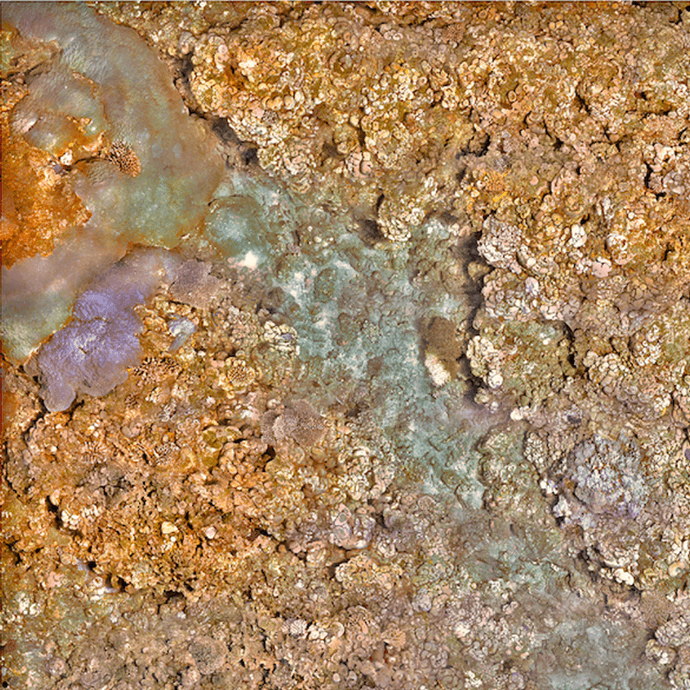

Algal-Dominated StateHigh-resolution photomosaic images taken at Maug Island, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, show a shift from a coral-dominated ecosystem (left) to an algae-dominated ecosystem (right) as a result of increased carbon dioxide in the environment. Image credit: NOAA

Scientists from NOAA and the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies at the University of Miami have documented a dramatic shift from vibrant coral communities to carpets of algae in remote Pacific Ocean waters where an undersea volcano spews carbon dioxide.

The new research published online August 10 in Nature Climate Change provides a stark look into the future of ocean acidification – the absorption by the global oceans of increasing amounts of human-caused carbon dioxide emissions. Scientists predict that elevated carbon dioxide absorbed by the global oceans will drive similar ecosystem shifts, making it difficult for coral to build skeletons and easier for other plants and animals to erode them.

“While we’ve done lab simulations of how increased carbon dioxide influences coral growth, this is the first field evidence that increasing ocean acidification results in such a dramatic ecosystem change from coral to algae,” said Ian Enochs, a scientist with NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies at the University of Miami who led the research. “Healthy coral reefs provide food and shelter for abundant fisheries, support tourism and protect shorelines from storms. A shift from coral to algae-covered rocks is typically accompanied by a loss of species diversity and the benefits that reefs provide.”

The research was conducted on Maug, an uninhabited volcanic island in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands about 450 miles from Guam. This location allowed scientists to single out a small geographic area that experiences carbon dioxide levels that vary from present day to those predicted for a hundred years in the future. Maug also provided researchers with an area with few other man-made stressors for coral, such as overfishing and pollution from land.

By setting up underwater instruments to continuously measure the effects of carbon dioxide, scientists were able to use this natural laboratory to show that coral cover decreased under higher levels of carbon dioxide, giving way to less desirable algae-covered rocks near the volcano’s vents.

See Full Article at Nature.com