The new research published by NOAA and international partners in Science finds as carbon dioxide emissions have increased in the atmosphere, the ocean has absorbed a greater volume of emissions. Though the volume of carbon dioxide going into the ocean is increasing, the percentage of emissions — about 31 percent — absorbed by it has remained relatively stable when compared to the first survey of carbon in the global ocean published in 2004.

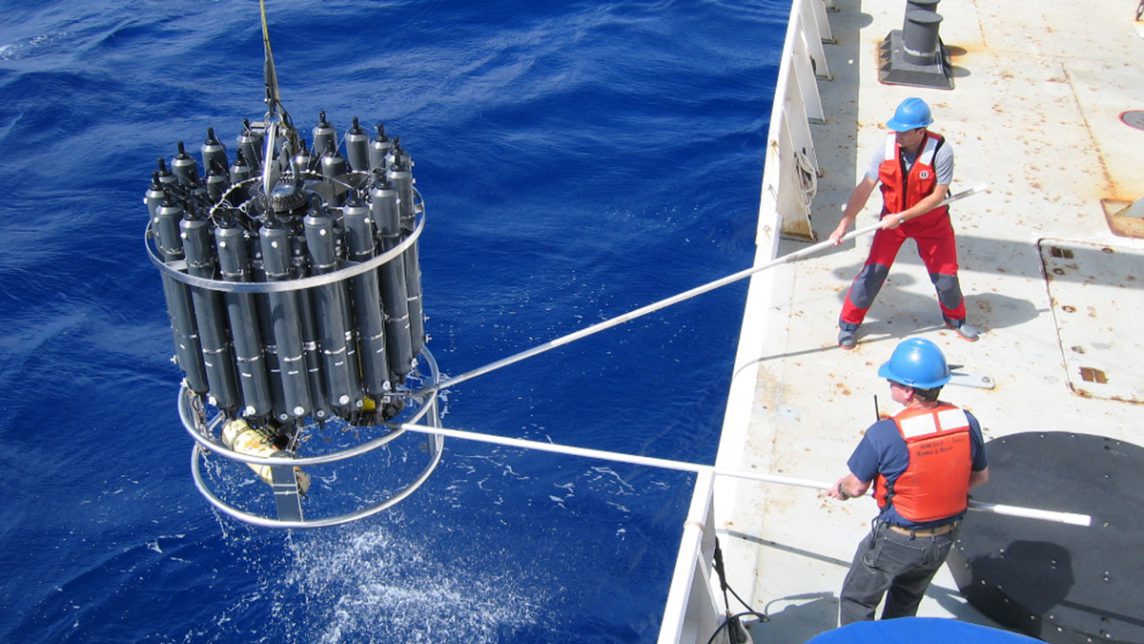

Live! Science at Sea: Gulf of Mexico Ocean Acidification Cruise

On July 18, NOAA AOML and partner scientists will depart on the Gulf of Mexico Ecosystems and Carbon Cycle (GOMECC-3) research cruise in support of NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Monitoring Program. This isn’t the first time researchers will head to sea in this region. Previous cruises have taken place along the east and Gulf of Mexico (GOM) coasts of the US in both 2007 and 2012. Together, these cruises provide coastal ocean measurements of unprecedented quality that are used both to improve our understanding of where ocean acidification (OA) is happening and how ocean chemistry patterns are changing over time. This will be the most comprehensive OA cruise to date in this region, set to include sampling in the international waters of Mexico for the first time. Ocean acidification is a global issue with global impacts, and international collaboration like this is vital to understanding and adapting to our changing oceans.

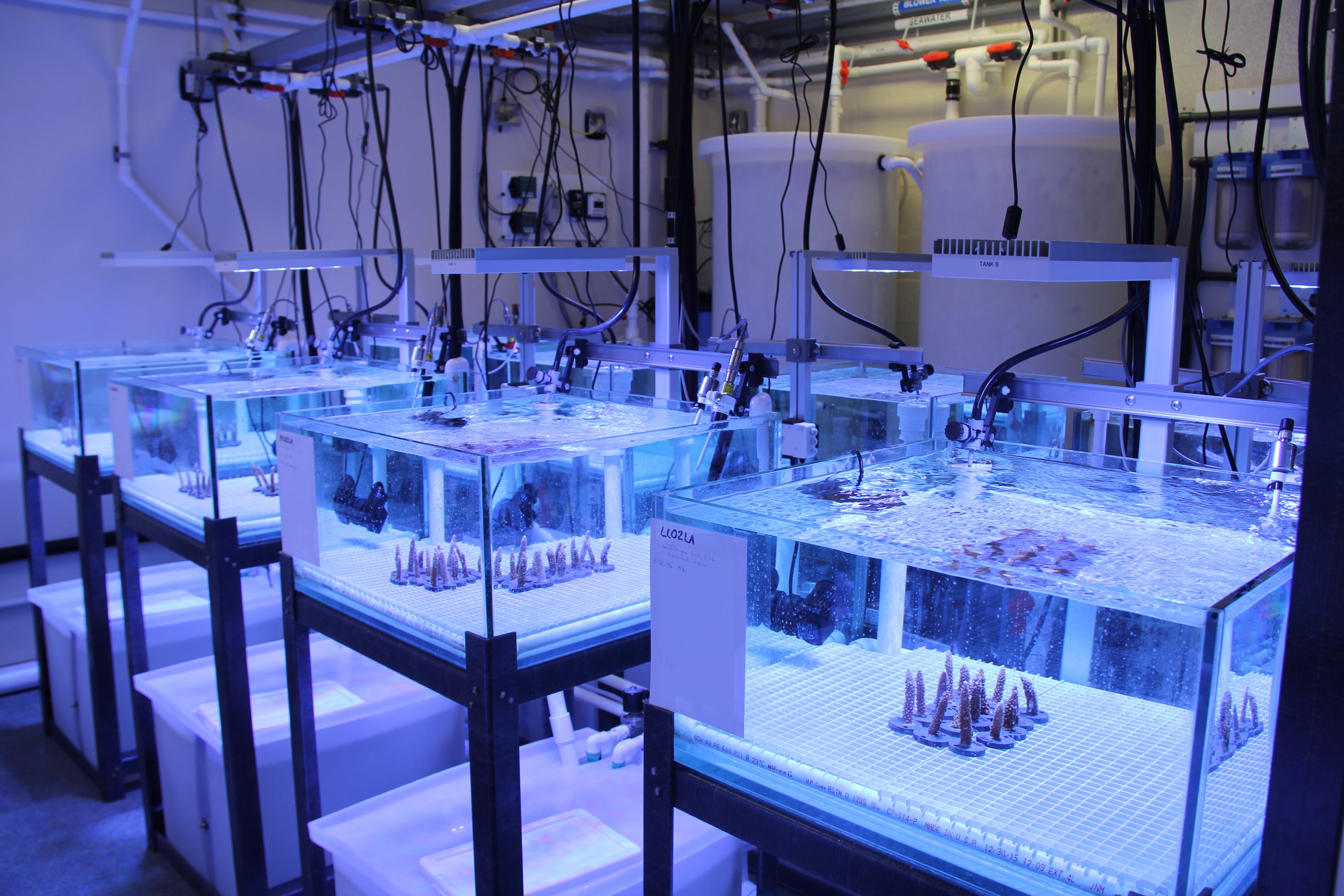

Researchers Explore Coral Resiliency in New Experimental Reef Laboratory

Coral researchers at AOML unveiled a new state of the art experimental laboratory this spring at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel campus. The new “Experimental Reef Laboratory” will allow NOAA scientists and colleagues to study the molecular mechanisms of coral resiliency. Modeling studies indicate that thermal stress and ocean acidification will worsen in the coming decades. Scientists designed the Experimental Reef Laboratory to study the combined effect of these two threats, and determine if some corals are able to persist in a changing environment.

Galapagos Islands: A Telling Study Site for Coral Reef Scientists

Coral scientists recently traveled to the Galapagos Islands to document coral reef health following the 2016-17 El Niño Southern Oscillation event (ENSO), which bathed the region in abnormally warm waters. Historically, these events have triggered coral bleaching and large-scale mortality, as seen in response to ENSO events of 1982-83 and 1997-98. Interestingly, these same reefs exhibited minimal bleaching in response to this most recent event. Scientists are determining whether this response is due to differing levels of heat stress, or an increased tolerance to warm water in the remnant coral communities.

Scientists Find Southern Ocean Removing CO2 from the Atmosphere More Efficiently

A research vessel ploughs through the waves, braving the strong westerly winds of the Roaring Forties in the Southern Ocean in order to measure levels of dissolved carbon dioxide in the surface of the ocean. (Nicolas Metzl, LOCEAN/IPSL Laboratory).

Volcanic Island of Maug Provides Natural Lab for Ocean Acidification

Ian Enochs, a scientist with NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies at the University of Miami, traveled in May to the Island of Maug in the Pacific Ocean as part of a NOAA expedition aboard NOAA Ship Hi’ialakai to study coral reef ecosystems. The expedition was led by NOAA’s Pacific Island Fisheries Science Center Coral Reef Ecosystem Division and the Pacific Marine Environmental Lab’s Earth-Ocean Interaction group. Enochs focused his research on underwater vents that seep carbon dioxide into the Pacific.

Why journey to the Island of Maug to study ocean acidification?

Maug is a unique natural laboratory that allows us to study how ocean acidificationaffects coral reef ecosystems. We know of no other area like this in U.S. waters. Increasing carbon dioxide in seawater is a global issue because it makes it harder for animals like corals to build skeletons.

What is the Island of Maug like?

Maug is an uninhabited volcanic island in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands about 450 miles north of Guam. The volcano breaks through the ocean surface in three areas to form islands and the relatively shallow water surrounding these islands is full of coral reefs. The underwater vents that seep carbon dioxide are found on the side of the caldera or crater formed by the volcano. Usually when I scuba dive, the moment I enter the water, air bubbles surround me and fade away quickly. On Maug, the bubbles never ceased and it felt like I was swimming in a glass of champagne.

| A funel is used to collect carbon dioxide gas bubbles from the seeps near the coral reefs. Photo credit: Open Boat Films/NOAA |

What are your goals for studying the carbon dioxide vents?

We’re mapping carbonate chemistry over time and space to examine the extent of carbon dioxide at the site. We’re looking at how that chemistry changes over this area as you get farther from the vents and what corresponding changes there are in the coral community. We hope to learn more about which coral species are especially sensitive to elevated carbon dioxide and which may be resilient. Finally, we will look at how elevated carbon dioxide levels in seawater may influence the response of various organisms over time, including their growth rate.

What does your sampling show so far?

The carbon dioxide appears to be strongly influencing the growth of corals and algae in a small area around the vents. While there is weedy algae near the vent due to high levels of carbon dioxide, this gives way to healthier coral reefs as you get farther away from the site.

How do you measure these effects over time?

This first trip has allowed us to begin measuring the effects of carbon dioxide and to place instruments in the area that will continuously measure temperature, light, the partial pressure of carbon dioxide, seawater pH, and water currents. When we return in August, we’ll have three months of data on how this special environment has been changing day to day. Additionally, we are able to measure coral growth over time by taking core samples and by using a special dye to measure new growth.

How can this research help our understanding of this and other areas of the ocean?

Research at the Maug site will help us determine the effects of elevated carbon dioxide on an entire natural ecosystem. Using this information, we’ll have a better understanding of how the rest of the ocean’s coral reefs may react to global increases in carbon dioxide and acidification. If the predictions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change remain the same, by the end of the century, the impact of ocean acidification on coral reefs around the world will be comparable to what we see on the reefs near Maug’s carbon dioxide seeps today.

Note: Ian Enochs’ research is part of a much larger research mission involving NOAA Fisheries, NOAA’s Coral Program, NOAA Research’s Pacific Marine Environmental Lab, the National Institute of Standards and Technology and other partners, including Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the University of Guam, and Open Boat Films. NOAA worked closely with CNMI coral management and monitoring experts at the Division of Coastal Resource Management and the Department of Environmental Quality. More information on the research mission is posted online.