NOAA contributed to a study published today in the journal Nature that compares the upward growth rates of coral reefs with predicted rates of sea-level rise and found many reefs would be submerged in water so deep it will hamper their growth and survival. The study was done by an international team of scientists led by the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom.

Coral Bleaching Study Offers Clues about the Future of the Florida Keys Reef Ecosystem

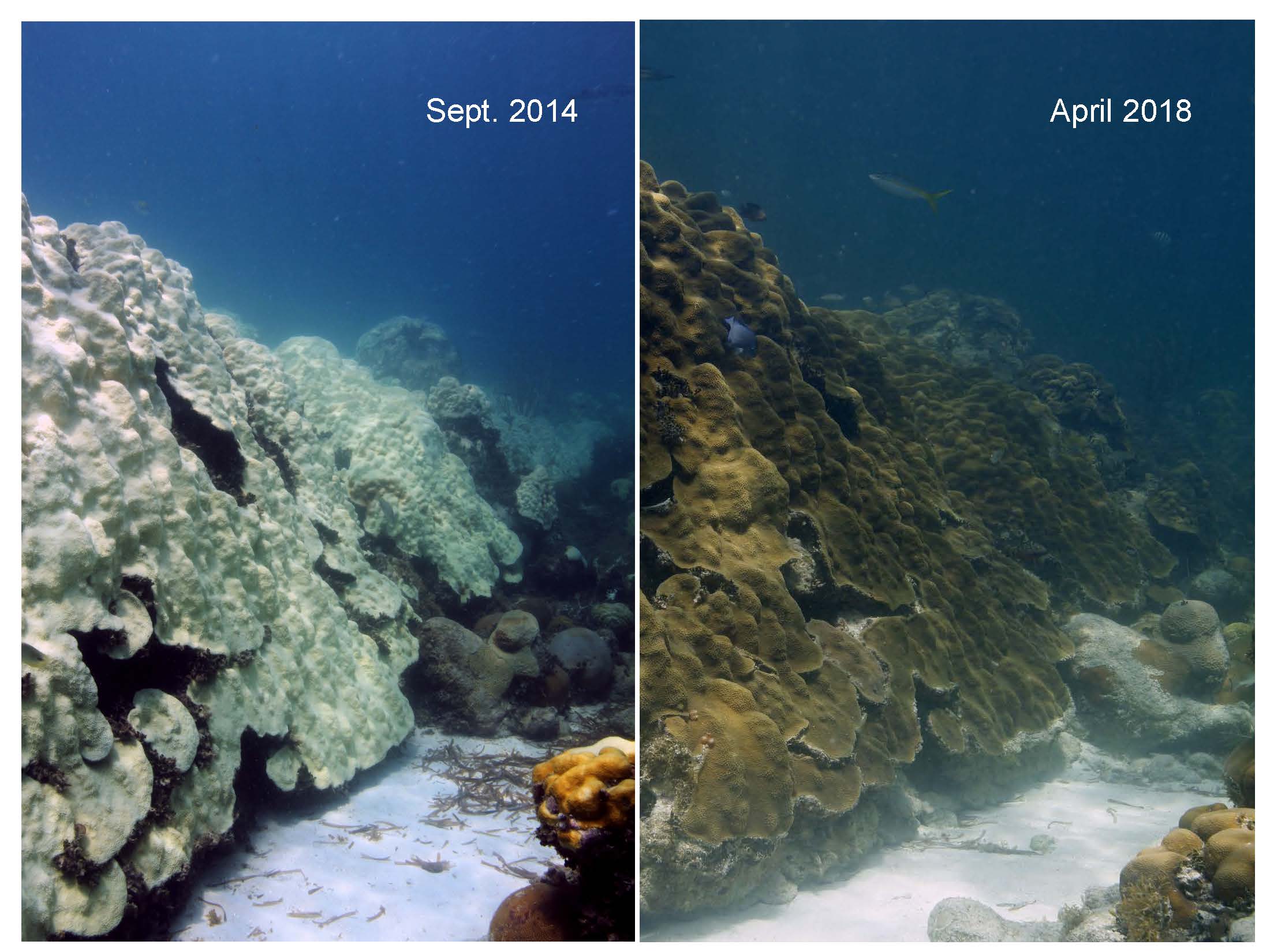

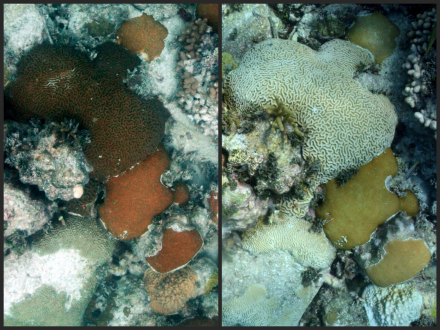

A recent study by AOML and partners identified coral communities at Cheeca Rocks in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary that appear to be more resilient than other nearby reefs to coral bleaching after back to back record breaking hot summers in 2014 and 2015 and increasingly warmer waters. This local case study provides a small, tempered degree of optimism that some Caribbean coral communities may be able to acclimate to warming waters.

The Science Behind Coral Bleaching in the Florida Keys

Photograph of bleached pillar coral on November 13, 2014 at Sand Key. Image credit: NOAA’s Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

2014 was a relatively warm summer in South Florida, and local divers noticed the effects of this sustained weather pattern. Below the ocean surface, corals were bleaching. In the month of August, the Coral Bleaching Early Warning Network, jointly supported by Mote Marine Lab and NOAA’s Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, received 34 reports describing paling or partial bleaching and an additional 19 reports indicating significant bleaching. Scientists continue to monitor the impact of this severe bleaching event to determine the extent of coral mortality.

This image, taken on November 13, 2014 by the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, shows a severely bleached pillar coral at Sand Key in the Florida Keys. Images like this one indicate that some regions and species will definitely be affected. Pillar coral is one of the species of coral listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

AOML Coral Ecologists Derek Manzello and Jim Hendee provide insight as to how the environmental conditions they are tracking indicate that a mass bleaching event is possible and even likely in the Florida Keys.

What is coral bleaching?

Coral colonies are made up of hundreds or even thousands of genetically identical individuals called polyps. These polyps have microscopic colorful algae called zooxanthellae living within their tissues. The zooxanthellae work like an internal symbiotic vegetable garden, carrying out photosynthesis and providing energy to their coral hosts, which helps reef-building corals create reef structures. When a coral bleaches, it expels its zooxanthellae, and can die within a matter of weeks unless the zooxanthellae populations are able to recover. The term bleaching is used because the dazzling colors of living corals are due to the zooxanthellae in coral tissue, and when zooxanthellae are lost, corals appear white, or “bleached.”

Extensive bleaching of the soft coral Palythoa caribaeorum on Emerald Reef, Key Biscayne, Fl. (Credit:NOAA)

What causes coral bleaching?

It is well established that elevated sea temperatures cause widespread coral bleaching. Warmer waters “stress” corals and trigger coral bleaching.

There are two types of heat stress that can trigger bleaching: (1) short-term, acute temperature stress (several days of very high water temperatures) and, (2) cumulative temperature stress (weeks of consistent moderately elevated water temperatures). Scientists have documented that coral communities around the world have different heat stress thresholds that typically trigger bleaching in response to heat stress. Scientists rely on long-term observing stations co-located with coral reefs to identify the specific conditions that correlate to bleaching within different regions.

What specifically triggers bleaching of coral found in the FL Keys?

Using long-term in situ datasets such as the Coastal-Marine Automated Network, or C-MAN, stations in the Florida Keys, AOML scientists identified specific patterns of warm waters on coral reefs that tend to precede bleaching

events. The indices that proved to be the most reliable indicators for bleaching for the Florida Reef Tract are maximum monthly sea surface temperature and the number of days >30.5 C (86.9 F).

What patterns have scientists noticed leading up to this most recent bleaching event?

Data from the Molasses Reef C-MAN station showed that the winter of 2014 was the warmest on record since these stations began recording data in 1988. The second warmest winter on record was the winter of 1996/97, which preceded back-to-back bleaching years in the Keys (1997/98) and was the worst bleaching event ever documented in the Florida Keys. The most recent significant bleaching event in the Florida Keys occurred in 2005, and there have been mild localized bleaching events since then.

The images above were taken from a coral colony at Cheeca Rocks in the Florida Keys. On the left shows the coral colony from July 2013. The image at the right shows the same coral colony in August 2014, with the colony now bleached. (Credit: NOAA)

The warm winter and warm water temperatures this spring caused scientists to start watching the long-term average water temperatures at these stations to see if the average daily temp was regularly reaching or exceeding 30.4 C, the trigger point for previous bleaching in the FL Keys. The Molasses Reef C-MAN site quickly approached this temperature threshold in July and August. Average temperatures were also warmer than normal at the Fowey Rocks C-MAN station and the Cheeca Rocks Atlantic Ocean Acidification Testbed in the northern Keys. With water temperatures now exceeding this threshold for more than thirty days, and reports of bleaching beginning to pour in, there are concerns about widespread bleaching throughout the region. To assess the extent of the bleaching event, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary has been working with its partners to monitor the current state of corals along the reef tract.

Jim Hendee is the acting division director of AOML’s Ocean Chemistry and Ecosystems Division. Jim leads the coral group at AOML and studies the environmental conditions that cause ecosystem-wide changes on coral reefs using in situ observing stations. Derek Manzello is a coral ecologist at AOML and leads research of the impacts of ocean acidification on coral reefs. Derek also studies the impact of other changes in environmental conditions on reefs such as temperature and tropical storm impacts.

Originally Published September 2014 by Shannon Jones

Tropical Cyclones Worsen Ocean Acidification at Coral Reefs

While tropical cyclones can dramatically impact coral reefs, a recent study reveals their passage also exacerbates ocean acidification, rendering reef structures even more vulnerable to damage. Calcifying marine organisms such as corals that thrive in alkaline-rich waters are increasingly imperiled as seawater becomes more acidic due to the ocean’s uptake of carbon dioxide. The detrimental effects upon these organisms have been documented, but less is known about how reefs might react to ocean acidification when coupled with an additional stress factor such as a tropical cyclone.

To assess how reefs might respond to such a scenario, coral researchers Derek Manzello, Ian Enochs, and Renee Carlton from the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School and NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, along with researchers from the University of Washington and NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program, collected data from reefs in the Florida Keys before, during, and after the passage of Tropical Storm Isaac in August-September 2012. Their findings appear online in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Tropical Storm Isaac as it passes over the Florida Keys on August 26, 2012. Image Credit: NOAA

The team analyzed seawater carbonate chemistry and environmental data from Cheeca Rocks and Little Conch Reef, both coral monitoring sites, as well as data from a coastal marine automated network station at Molasses Reef.

They found that Tropical Storm Isaac caused both an immediate and prolonged decline in seawater pH and carbonate saturation state at the two coral reef sites studied. The post-storm pH levels were the lowest recorded values to date from over two years of high-resolution data measured at the Cheeca Rocks ocean acidification monitoring site, and this depression in pH lingered for more than a full week.

Prior concerns regarding ocean acidification and coral reefs assumed carbonate undersaturation would not occur at reefs in the foreseeable future due to their location within the highly supersaturated tropical oceans. However, the study demonstrates that carbonate undersaturation at reefs will occur from even the passage of a modest tropical storm when coupled with ocean acidification.

Coral bleaching at Cheeca Rocks in the Florida Keys. Image credit: NOAA

With climate models projecting a steady increase in the rate of ocean acidification, along with stronger, more frequent tropical cyclones, the future for coral reefs thus appears bleak. In the coming decades, tropical cyclones could depress carbonate seawater saturation levels to such an extent that reefs will undergo periods of post-storm dissolution, weakening coral reef frameworks and worsening the widespread ecological and economic consequences of the coral reef crisis.