Take a virtual tour of the lab here.

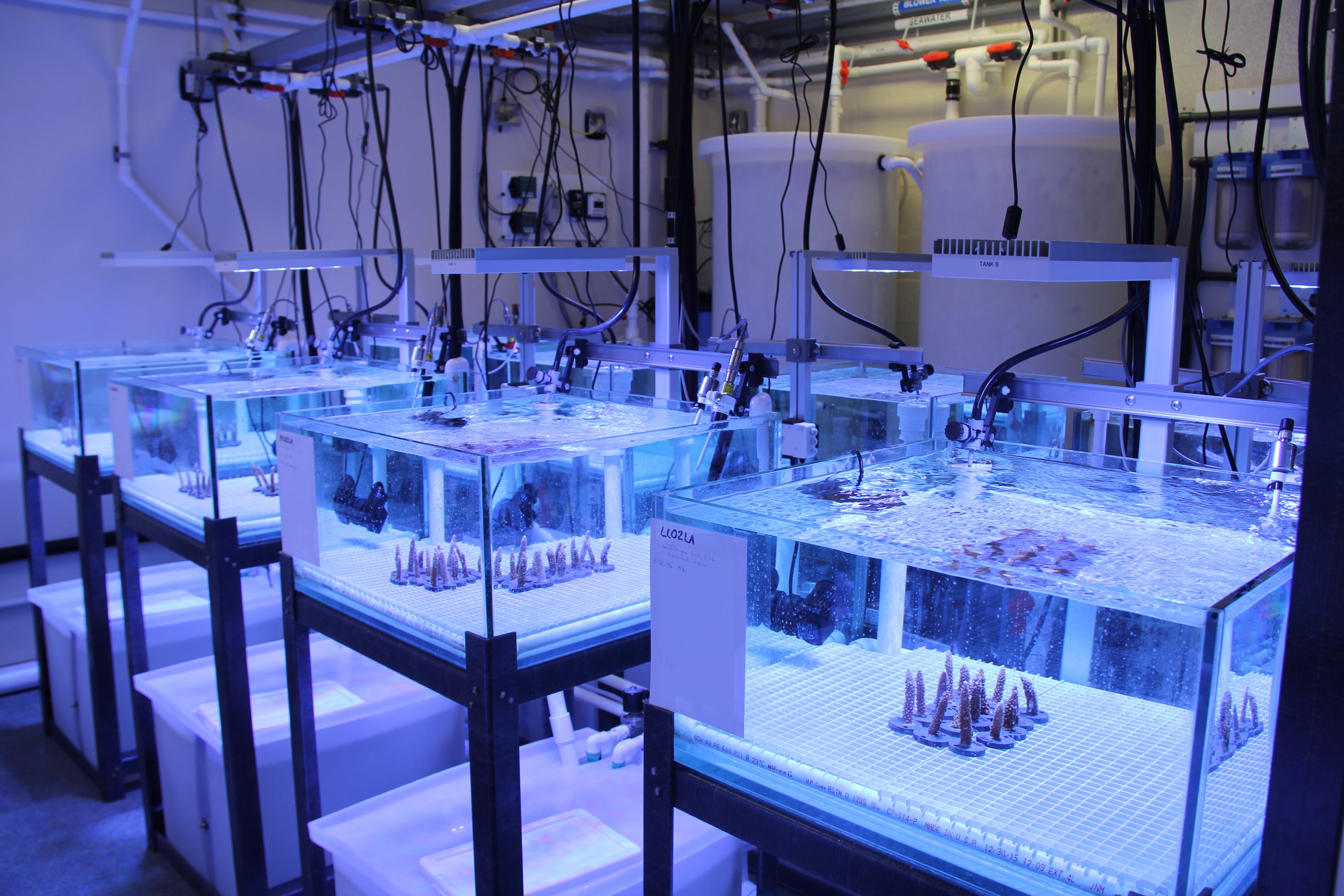

Coral researchers at AOML unveiled a new state of the art experimental laboratory this spring at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel campus. The new “Experimental Reef Laboratory” will allow NOAA scientists and colleagues to study the molecular mechanisms of coral resiliency. Modeling studies indicate that thermal stress and ocean acidification will worsen in the coming decades. Scientists designed the Experimental Reef Laboratory to study the combined effect of these two threats, and determine if some corals are able to persist in a changing environment.

“We need to create the future today, in order to ensure coral survival in future oceans,” explains coral ecologist and lab designer Ian Enochs.

The lab enables researchers to precisely regulate CO2 levels as well as temperature, in order to observe how coral and reef organisms respond to thermal stress and ocean acidification stress. Studies have shown that elevated temperatures cause corals to bleach, while ocean acidification reduces the ability of corals to build their skeletons, and accelerates the rate of coral deterioration by bioeroding organisms.

Featuring 16 separate aquaria, this state of the art lab seeks to emulate as natural an environment as possible. Highly accurate temperature and pH sensors are located in each tank, all linked to the lab’s main computer, which carefully monitors and controls heating, cooling and the flow of CO2 gas in the individual tanks. LED lights installed above the aquaria provide a variable range of light levels that, if needed, can be adjusted to stimulate sunlight intensity that occurs during coral bleaching. Seawater for the aquaria comes from Biscayne Bay, which is adjacent to both AOML and the Rosenstiel School on Virginia Key.

The intricacies of the laboratory design will allow for a myriad of different collaborative studies by the local scientific community on Virginia Key. Scientists and students can use the lab to look at the response of several different genera of corals to ocean acidification, thermal stress, or the synergistic effects of both. The versatility of this laboratory permits an array of experimental designs, including – but not limited to – observations of coral calcification, patterns of skeletal construction and morphological form, rates of bioerosion, rates of photosynthesis and respiration, coral-symbiont interactions, stress hardening and land-based pollution experiments.

This lab is unique in that it allows researchers to “dial in” multiple daily fluctuations in carbonate chemistry observed in the natural environment, as well as being programmed to simulate future CO2 levels and ocean temperatures. Projects that involve coral restoration and replenishment – for example the University of Miami’s Rescue A Reef program – will require a greater understanding of how corals respond to stress. The ability to observe how organisms are responding to current conditions or how they will respond to projected future conditions makes the laboratory a versatile tool for NOAA scientists and collaborators.

Coral reefs in South Florida currently support numerous businesses, jobs, and revenue for the local economy, in addition to providing important ecological goods and services. However, as coral reefs decline, so do the economic goods and services they provide. Therefore, an enhanced understanding of coral responses to increased levels of stress will be beneficial in supporting their resilience, and enable them to survive a marine environment in transition.

Originally Published in June 2017 by Sierra Sarkis