Observaciones del océano

para una economía azul sostenible

Observar la tecnología para conservar y gestionar los recursos y proteger los ecosistemas marinos

Quiénes somos

Los científicos del AOML utilizan las observaciones oceánicas para ayudar a proteger las especies, proporcionar información para apoyar las decisiones de gestión de los ecosistemas y comprender y predecir cómo cambian las condiciones ambientales. Trabajamos con socios como el Servicio Nacional de Pesquerías Marinas de la NOAA, la Guardia Costera de los Estados Unidos y socios universitarios en apoyo de la misión de la NOAA de conservar y gestionar los ecosistemas y recursos costeros y marinos. Utilizando los últimos avances en tecnología de observación, nuestros oceanógrafos pueden proporcionar herramientas para mejorar la evaluación de las poblaciones y la gestión de las especies pesqueras comerciales, ayudar a mantener la salud de los ecosistemas y proteger las especies marinas en peligro.

Este programa apoya cuatro objetivos principales:

- Mejorar la seguridad de los buques y proteger a las ballenas francas en peligro de extinción reduciendo el número de colisiones con buques gracias al Sistema de Notificación Obligatoria de Buques.

- Mejorar la evaluación de las poblaciones y la gestión del atún rojo del Atlántico mediante la creación de herramientas para supervisar los cambios en las zonas de hábitat favorables.

- Llevar a cabo investigaciones para evaluar cómo el calentamiento previsto de los océanos puede afectar al hábitat futuro de las especies de peces de importancia comercial.

- Estudiar el reclutamiento de larvas dentro del sistema arrecifal mesoamericano y el Caribe para determinar la importancia de la conectividad regional para las poblaciones locales de peces.

Leer más noticias

Repercusiones de la investigación y conclusiones principales

Del éxito de la notificación obligatoria de buques

De la investigación pesquera práctica y los datos derivados de los sistemas de observación global

El índice del atún rojo del Atlántico puede identificar el hábitat adecuado para el atún rojo

El índice del atún rojo del Atlántico puede identificar el hábitat adecuado para el atún rojo. Este índice proxy de larvas puede explicar alrededor del 58% de la variabilidad del reclutamiento y se utiliza actualmente para guiar el crucero de investigación interdisciplinar de la NOAA.

Esperanza para la pesca del atún rojo del Atlántico en el norte del Golfo de México

Las investigaciones realizadas en el AOML, basadas en el AR4 del IPCC, muestran que la corriente de bucle podría ralentizarse hasta un 25% a finales del siglo XXI, lo que reduciría el agua cálida que llega al Golfo desde el Caribe. Esto podría contrarrestar el calentamiento superficial previsto, especialmente en el norte del Golfo de México, que es una zona conocida de desove del atún rojo del Atlántico.

Productos del océano

Informe sobre la inundación de Sargassum

El sargazo, un tipo de alga flotante, puede inundar las zonas costeras y causar importantes daños económicos, medioambientales y de salud pública. Estos informes evalúan el riesgo de inundación de la costa en las regiones del Caribe y el Golfo de México utilizando los campos del Índice Alternativo de Algas Flotantes generado por la Universidad del Sur de Florida. Esta herramienta analiza áreas a 50 km (31 millas) por píxel y a, clasifica el riesgo de inundación de sargazo.

Índice de atún rojo

El índice del atún rojo proporciona información detallada sobre el hábitat del atún rojo a los organismos de gestión para informar la toma de decisiones. El índice rastrea el hábitat favorable para el atún rojo en tiempo casi real y es utilizado por NOAA Fisheries en las evaluaciones de las poblaciones. Con límites de capturas mejor informados e información sobre su ubicación, las operaciones de pesca comercial pueden realizar sus capturas con éxito y de forma sostenible.

Sistema obligatorio de notificación de buques

El sistema de notificación obligatoria a los buques ayuda a reducir la mortalidad por colisión con los buques de la población de ballenas francas del Atlántico Norte, que ha luchado por recuperarse de una población disminuida a pesar de ser una especie protegida. Este sistema de notificación tiene como objetivo educar a los marineros mercantes sobre la difícil situación de la ballena franca, y proporcionar información sobre la reducción del riesgo de colisiones con buques.

Investigación del hábitat orientada al futuro

El atún rojo del Atlántico desova en el Golfo de México de abril a junio. Aunque el atún rojo puede tolerar aguas más frías que otros atunes tropicales, se ve afectado negativamente por las aguas cálidas y evitará los lugares con características más cálidas, como la corriente de bucle en el Golfo de México. Esta investigación examina el hábitat tolerable del atún rojo del Atlántico bajo varios escenarios diferentes de calentamiento del océano para estudiar el impacto potencial de un océano que se calienta en esas pesquerías en el Golfo de México.

Investigación sobre el sargazo

Un alga flotante comúnmente encontrada, conocida como "Sargassum", ha inundado las costas del Atlántico tropical y el Caribe desde 2011. Estas algas flotan en la superficie del mar, donde pueden agregarse para formar grandes esteras en mar abierto. Un estudio de 2020 dirigido por investigadores del AOML muestra cómo el Sargassum entró y floreció en el Atlántico tropical y el Caribe. Se ha desarrollado una herramienta basada en esa investigación, conocida como Informe sobre la Inundación de Sargazo (SIR), para ayudar a los gestores a hacer frente a estas inundaciones periódicas.

Se ha creado un formulario de notificación de Sargassum para ayudar a los científicos a mejorar el seguimiento y la investigación de Sargassum. Se invita al público a rellenar la encuesta que figura a continuación y a subir fotos de avistamientos de Sargassum para ayudar a los científicos a comprender y mejorar la vigilancia del Sargassum.

Hipótesis de la inundación de sargazos

Informe sobre la inundación de Sargassum

Formulario de notificación de sargazos

Preguntas frecuentes sobre el sargazo

Información general sobre el sargazo

Sargassum es un tipo de alga parda flotante, comúnmente llamada "alga marina". Estas algas flotan en la superficie del mar, nunca se adhieren al fondo marino, y pueden agregarse para formar grandes esteras en mar abierto.

Históricamente, la mayor parte del Sargassum se concentraba en el mar de los Sargazos, en el Atlántico Norte occidental, con algunas pequeñas cantidades en el Golfo de México y el mar Caribe. En 2011, el área de distribución geográfica se amplió, y cantidades masivas de Sargassum se desplazaron hacia el oeste, al Mar Caribe, el Golfo de México y el sur del Atlántico tropical, llegando a Florida, Puerto Rico, las Islas Vírgenes estadounidenses y la mayoría de las islas y zonas costeras del Mar Caribe.

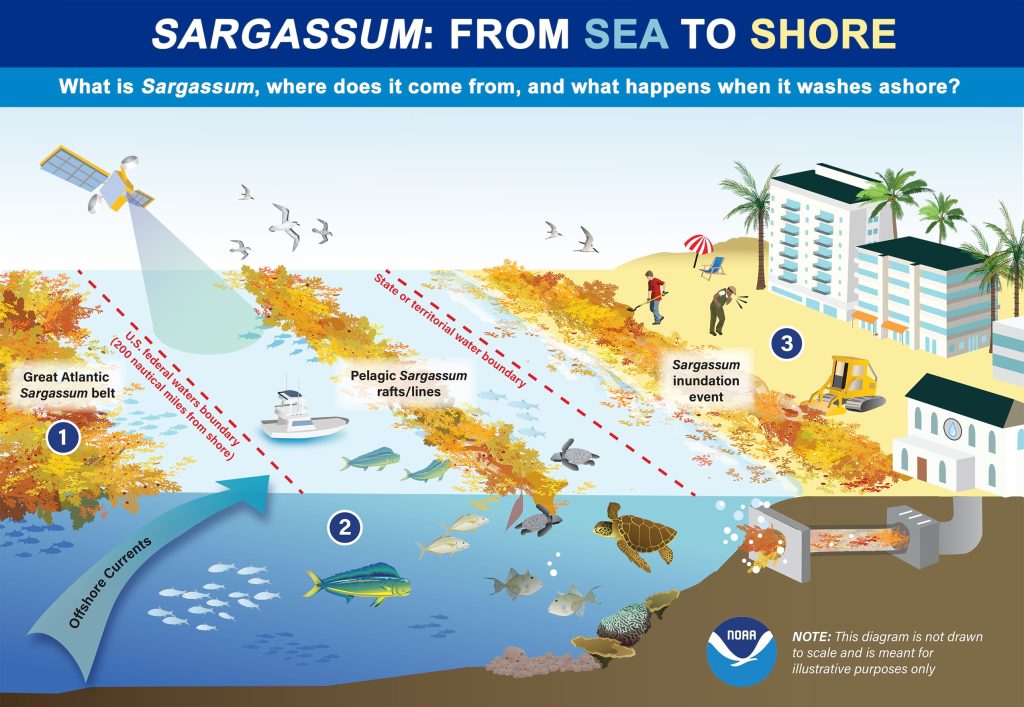

Esta infografía ilustra el movimiento del sargazo del mar a la costa. En el mar , el sargazo constituye un importante hábitat para los peces y la fauna. Sin embargo, esta alga flotante a menudo llega a la costa en grandes cantidades debido a los fuertes vientos y corrientes de agua. La llegada masiva de estas algas a la costa puede dañar los ecosistemas costeros, ahuyentar a los turistas y suponer una amenaza para la salud pública. La NOAA está trabajando para ayudar a las comunidades costeras a hacer frente al creciente problema de lo que los expertos llaman "eventos de inundación de Sargassum." Crédito de la imagen: NOAA National Ocean Service

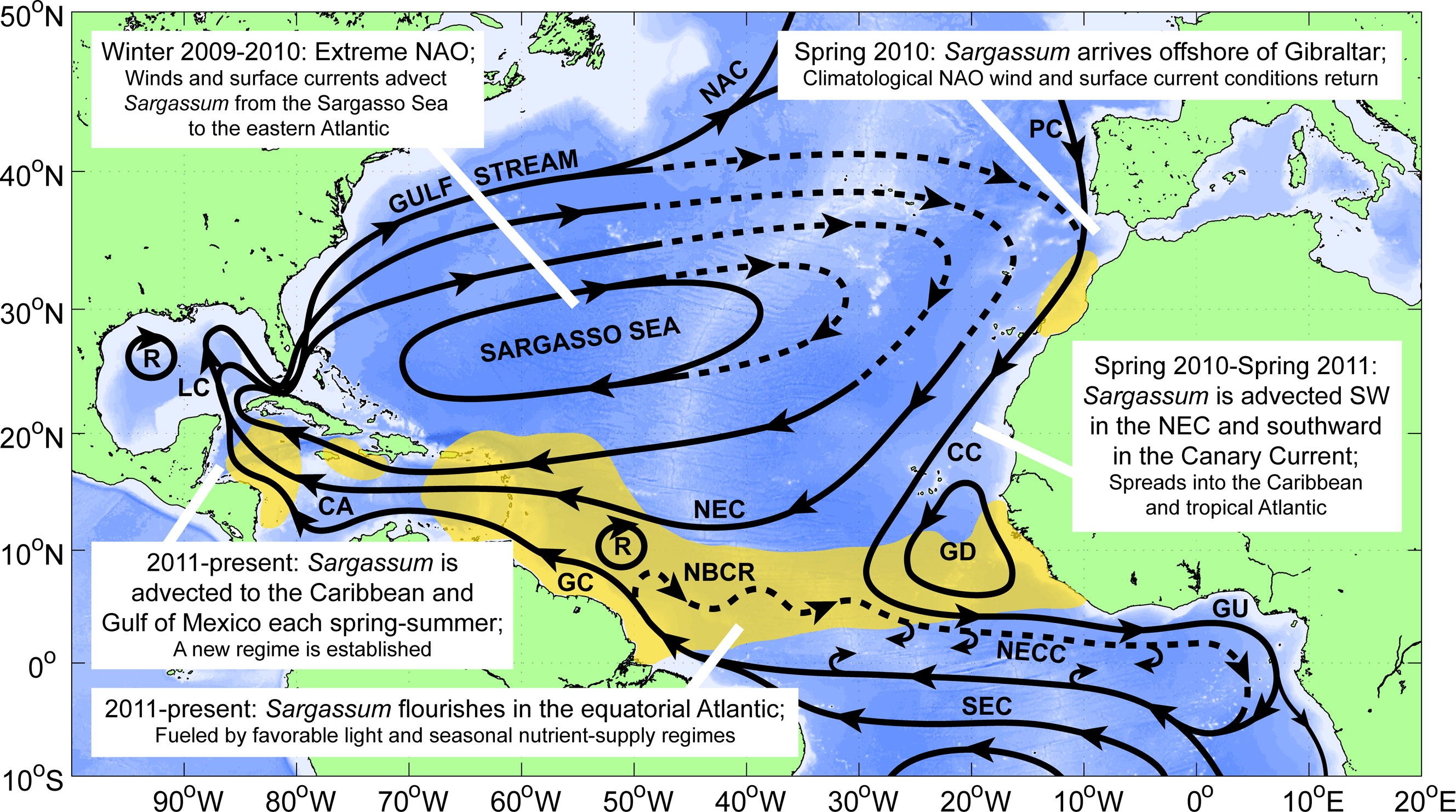

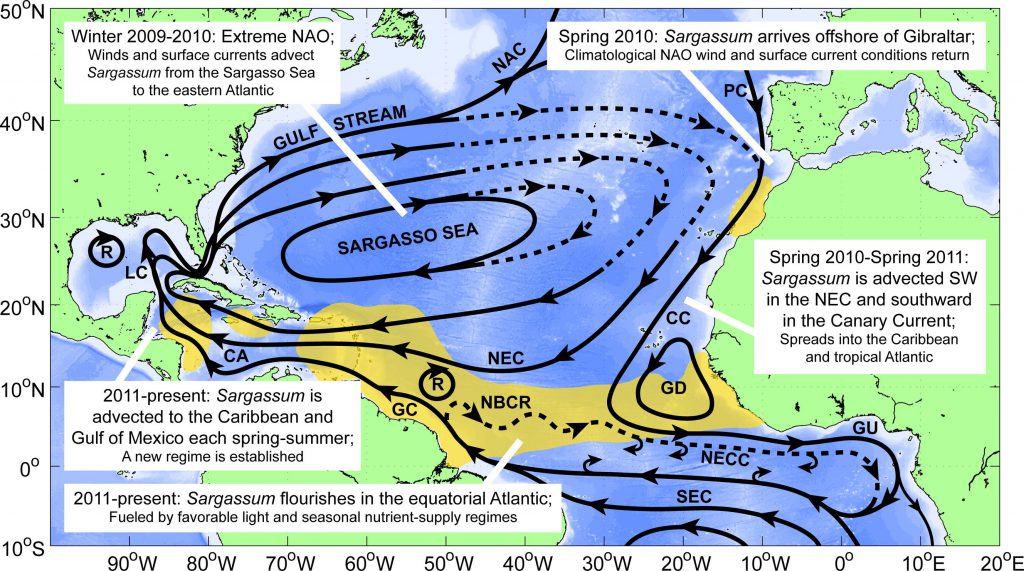

Investigadores están todavía evaluando varias hipótesis sobre la causa de este primer acontecimiento extremo documentado. Una hipótesis propone que durante el invierno de 2009-2010, los vientos que normalmente soplan hacia el este, de América a Europa, se fortalecieron y se desplazaron hacia el sur de forma más drástica y persistente que en cualquier otro momento del registro de 1900-2020. Este cambio en los vientos desencadenó una dispersión de larga distancia hacia el este de Sargassumdesde el Mar de los Sargazos hacia la Península Ibérica en Europa y África Occidental. Tras salir del Mar de los Sargazos, el Sargassum derivó hacia el sur en la corriente de Canarias y entró en los trópicos. Una vez en este nuevo y favorable hábitat del Atlántico tropical, con abundante luz solar, aguas cálidas y disponibilidad de nutrientes, el Sargassum floreció y ha seguido creciendo.

Además del cambio de los patrones de viento, otras hipótesis incluyen una combinación de factores, como la variación del caudal de los principales ríos (por ejemplo, el Amazonas y el Orinoco), la concentración de nutrientes (nitrógeno y fósforo) en los océanos, el aumento de la cantidad de fósforo debido al polvo sahariano, la temperatura del agua y las escorrentías fluviales.

Una vez establecida una nueva población, el Sargassum se agrupa casi todos los años, a partir de enero/febrero, en una enorme hilera o "cinturón" al norte del Ecuador, a lo largo de la región donde convergen los vientos alisios. A finales del invierno y principios de la primavera, el Sargazo se desplaza hacia el norte con los vientos y corrientes estacionales. En junio, este cinturón puede extenderse por todo el Atlántico tropical central. Grandes porciones de estas algas son transportadas hacia el Mar Caribe y el Golfo de México a través de los sistemas de corrientes Ecuatorial del Norte y del Caribe.

Desde 2011, grandes acumulaciones de Sargazo se han producido todos los años en el mar Caribe, el golfo de México y el Atlántico tropical, pero la cantidad puede variar de un año a otro.

La presencia de Sargassum se da en amplias zonas desde el Atlántico tropical en el este, hasta el Golfo de México en el oeste, aproximadamente 5.000 kilómetros desde el Atlántico tropical oriental hasta el oeste de la costa mexicana en el Mar Caribe. Sargassum no se extiende como un manto (o mancha) que cubra toda la superficie del océano en estas regiones. Por el contrario, Sargassum flota en parches que varían en tamaño desde unos pocos centímetros a cientos de metros. Algunos de estos parches llegan a las zonas costeras, incluidas playas, puertos e incluso sistemas de toma de agua potable. El área que cubren estos parches ha sido significativamente mayor en los últimos años que antes de 2011.

Sargazoen cantidades normales, proporciona hábitat, alimento, protección y zonas de reproducción a cientos de especies marinas diversas, incluidas especies de importancia comercial, como el atún y el pez espada, que se alimentan de la vida marina más pequeña presente en el Sargazo Sargassum. Si Sargassum llega a la costa en cantidades pequeñas/normales, puede ayudar a evitar la erosión de las playas.

En alta mar, el sargazo es un hábitat importante para peces, tortugas marinas y otros organismos marinos, pero al acumularse cerca de las costas puede asfixiar valiosos corales, praderas marinas y playas. Al llegar a la costa, las algas empiezan a descomponerse, atrayendo moscas y otros insectos. Además, durante su descomposición, el sargazo produce gas sulfhídrico, que huele a huevos podridos, lo que repele a los bañistas y afecta a la industria turística, que depende de las condiciones prístinas del océano. El s argazo también puede afectar a la navegación, bloquear la entrada de agua en las plantas desalinizadoras y afectar a los ecosistemas bentónicos si se hunde en el fondo del océano.

Los estudios sobre el impacto del Sargassum en la salud humana empezaron hace muy poco y es un tema que necesita más tiempo para ser plenamente comprendido. Sin embargo, cuando se descompone, el Sargassum libera sulfuro de hidrógeno (un gas) que puede causar problemas de salud respiratoria. También se sabe que el sargazo suele contener metales pesados que pueden ser tóxicos para los seres humanos y los animales.

Esfuerzos de la NOAA

Investigadores del AOML de la NOAA y del Servicio Nacional de Información y Datos Medioambientales por Satélite(NESDIS) de la NOAA, así como de la Universidad del Sur de Florida, elaboraron el Informe experimental sobre la inundación de s argazo (SIR) para ofrecer una visión general de la extensión del sargazo en el océano y del riesgo de que éste llegue a las aguas costeras, playas y litorales de las regiones del Caribe, el Golfo de México y el sureste de Florida.

La investigación llevada a cabo en el AOML en colaboración con la Universidad de Miami, la Universidad del Sur de Florida y LGL Ecological Research (TX) también está ayudando a identificar cómo se extiende el Sargassum por el Caribe, el Golfo de México y el Atlántico tropical, evaluando el papel de las corrientes oceánicas, los vientos y las olas en su movimiento. Este trabajo incluye experimentos de campo realizados para supervisar la trayectoria real del Sargassum mediante dispositivos de seguimiento por satélite y traineras de superficie e imágenes por satélite, así como la representación física del Sargassum en simulaciones teóricas y numéricas. Al final de estas FAQ figura una lista de manuscritos científicos derivados de esta investigación.

Además, una colaboración entre investigadores del AOML y Fearless Fund estudia cómo las algas marinas, incluido el Sargassum, eliminan de forma natural el dióxido de carbono de las aguas oceánicas y lo retienen en las algas. Este proyecto pretende ofrecer una solución de gestión a la inundación a gran escala de las playas, al tiempo que reutiliza el Sargassum.

Como parte del Programa Científico RESTORE de la NOAA, el Departamento de Pesca de la NOAA, la Universidad del Sur de Mississippi y la Universidad del Sur de Florida están evaluando el papel delSargassum como hábitat de cría de peces en el norte del Golfo de México. Este proyecto pretende comprender la relación entre la distribución y abundancia de Sargassum y su capacidad para servir de criadero de peces juveniles para especies de importancia recreativa y comercial. Los resultados se utilizarán para desarrollar una previsión que pueda informar a los gestores pesqueros de los cambios en el Sargassum y el reclutamiento de peces.

Científicos de la Universidad de Rhode Island y de la Institución Oceanográfica Woods Hole examinan las repercusiones sociales de las inundaciones de sargazo en el Caribe en el marco de un estudio financiado por los Centros Nacionales de Ciencias Oceánicas Costeras de la NOAA. El proyecto, de tres años de duración, evalúa las repercusiones económicas, el bienestar humano y los comportamientos y percepciones individuales asociados a estos fenómenos, así como un amplio compromiso con los miembros de la comunidad y las partes interesadas pertinentes. Los resultados de este estudio ayudarán a los gestores costeros locales y regionales a gestionar las inundaciones de Sargassum y las actividades de mitigación.

Los Centros Nacionales para las Ciencias Oceánicas Costeras(NCCOS ) de la NOAA están iniciando un nuevo estudio para detectar y analizar contaminantes químicos en las esteras de Sargassum de Puerto Rico, las Islas Vírgenes de EE.UU. y Florida. Los científicos buscarán en las muestras concentraciones de metales traza, sustancias orgánicas y perfluoroalquilos y polifluoroalquilos (PFAS), muchos de los cuales son muy persistentes. Esta investigación proporcionará a los gestores información esencial para gestionar, eliminar, reutilizar o reciclar con seguridad el sargazo en las jurisdicciones locales.

Más información:

El informe experimental Informe sobre la inundación de sargazo (SIR) proporciona una visión general de la zona de actual Sargazo y el riesgo de Sargazo en las regiones costeras del Caribe, el Atlántico tropical y el Golfo de México. El SIR es un producto experimental que se actualiza semanalmente y utiliza datos obtenidos por satélite para estimar el potencial de Sargazo llegue a la costa.No se trata de una previsión.

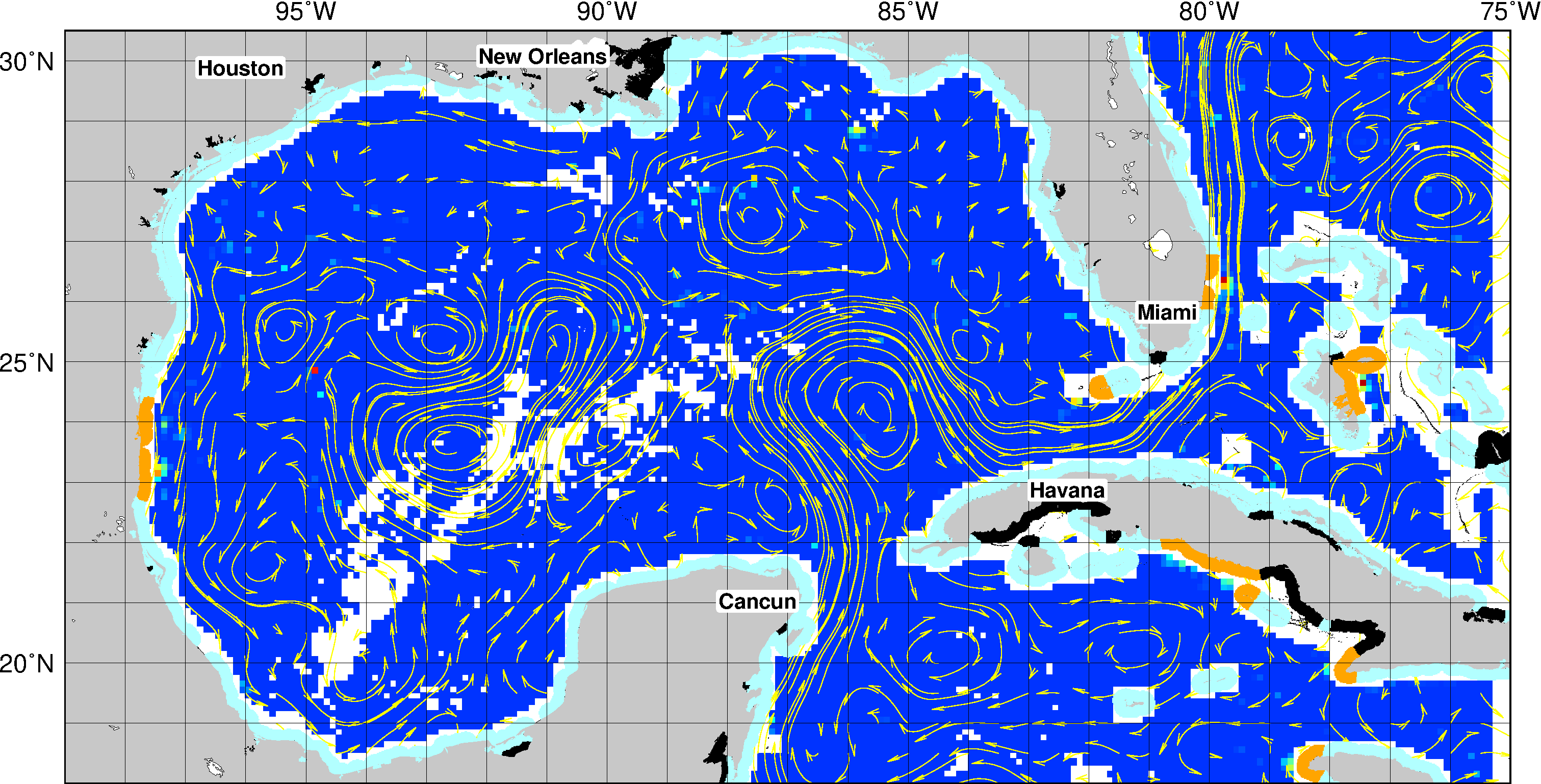

SIR muestra las condiciones actuales de Sargazo e identifica las zonas costeras donde el Sargassum se encuentra en un radio de 50 km (30 millas) y, por tanto, pueden verse afectadas por el Sargazo en los días/semanas siguientes. La incidencia real de la inundación costera dependerá en gran medida de las condiciones locales de corriente, marea, viento y oleaje. El potencial de inundación se clasifica entonces en tres niveles: bajo, medio y alto, que se basan en gran medida en la distancia entre las manchas de Sargazo a la costa, y la densidad y extensión de estos parches. Las líneas costeras se codifican por colores en función de estos tres niveles.

SIR sirve como fuente de información sobre la distribución actual de Sargassum en distintas zonas, su potencial para llegar a la costa, y puede utilizarse para hacer un seguimiento de los movimientos pasados de Sargassum en la región, lo que puede permitir a los investigadores formular hipótesis sobre la evolución del riesgo en el tiempo.

Los investigadores están utilizando imágenes de satélite para identificar las zonas de mar abierto donde el Sargassum y calculan dónde pueden producirse varamientos en función de la densidad y la proximidad del Sargassum de la costa. Aunque no se trata de un pronóstico, ayuda a las comunidades a prepararse para posibles inundaciones. Los investigadores utilizan sus conocimientos sobre las corrientes oceánicas, los vientos y las condiciones del oleaje para mejorar estas estimaciones.

Identificación de Sargassum desde el espacio es compleja. Sargassum puede observarse indirectamente por satélite desde el espacio midiendo cómo se refleja la luz en la superficie del océano.

El AOML está llevando a cabo una investigación para evaluar el impacto de las corrientes oceánicas, los vientos y las olas en la distribución y trayectoria del Sargassumcon el fin de aumentar la precisión de Sargazo Sargassum. También realizamos un seguimiento como parte del Nodo del Caribe de NOAA NESDIS CoastWatch alojado en el AOML: https://cwcgom.aoml.noaa.gov/cgom/OceanViewer/

Actualmente los SIR se crean a partir de una cantidad derivada del satélite (densidad de Sargassum), estimada por la Universidad del Sur de Florida a partir del satélite de la NASA MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) de la NASA a bordo de los satélites Aqua y Terra.

Dado que MODIS se acerca al final de su misión, NOAA CoastWatch y el AOML están trabajando en la actualización de este producto para integrar datos de sensores adicionales que proporcionen una mejor cobertura, especialmente en las zonas costeras, como VIIRS a bordo de las misiones de satélites en órbita polar SNPP, NOAA-20 y NOAA-21, OLCI (Ocean and Land Colour Instrument ) a bordo de los satélites Sentinel-3A y Sentinel-3B, y MSI (Multispectral Instrument) a bordo de los satélites ópticos Sentinel-2A y Sentinel-2B de la ESA (Agencia Espacial Europea).

Las estimaciones proporcionadas por el SIR se han validado en diferentes zonas del Mar Caribe y del Océano Atlántico tropical y se ha enviado una publicación de este trabajo a la revista Aquatic Botany Journal de Elsevier.

Un esfuerzo internacional de ciencia ciudadana para recoger principalmente observaciones costeras de Sargassum está dirigido por la Universidad Internacional de Florida, a través de Epicollect Observación del sargazo de Epicollect. Epicollect es una aplicación móvil y web para recoger datos científicos. NESDIS CoastWatch y AOML contribuyen a este esfuerzo a través de su Sargassum página web de ciencia ciudadana aquí.

Marzo 2023 Información y actualizaciones

El movimiento, la extensión y la densidad del Sargassum es muy complejo: crece, se hunde y se desplaza en función de las corrientes oceánicas, los vientos y las olas. Por ello, a veces no es posible describir trayectorias de antemano, sino una descripción general de cómo han cambiado la extensión y la densidad medias. Proyectar una trayectoria precisa del Sargazo es un reto y un área actual de intensa investigación. Por el momento, no es posible predecir el momento de la varada del Sargassum.

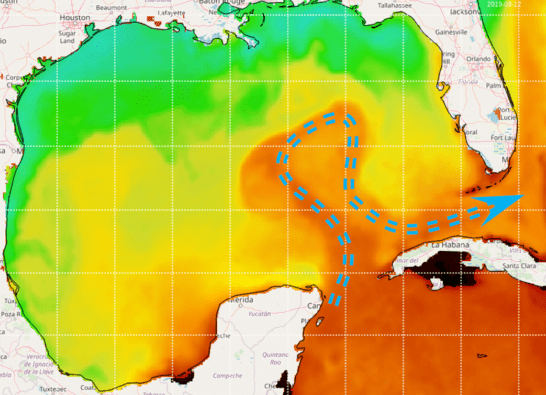

Hay dos fuentes principales de Sargassum localizadas en el Golfo de México, una es local y alcanza su punto máximo en abril-mayo, y la segunda es el Mar Caribe que alcanza su punto máximo durante los meses de verano. Grandes cantidades de Sargassum se encuentran actualmente en el Mar Caribe, moviéndose hacia la Península de Yucatán, y esparciéndose a través del Golfo de México por la Corriente de Lazo.

La Corriente en Bucle fluye a través del Estrecho de Florida y frente a la costa este de Florida, donde se la conoce como Corriente de Florida, y seSe conoce como Corriente de Florida y desemboca en la Corriente del Golfo cuando se dirige hacia el norte por la costa oriental de Estados Unidos. La fuerte Corriente en Bucle transporta actualmente cantidades moderadas de Sargazo que anteriormente se encontraban en el Mar Caribe, con cantidades mayores potencialmente en camino. Parte del Sargassum en el Golfo de México también se originó localmente. Que el Sargassum llegue a la costa de Florida, incluidos los Cayos de Florida, dependerá en gran medida de las condiciones locales de viento, oleaje y marea. Dada la complejidad de su movimiento, crecimiento y descomposición, no es posible predecir el momento de la varada. Sin embargo, dado el tamaño y el número de los actuales Sargassum actuales, es muy probable que el Sargazo transportado por la corriente de Florida pueda alcanzar la costa de Florida a pesar de las condiciones de viento y oleaje. A mediados de marzo de 2023, las observaciones por satélite indican que parte de este Sargassum ya ha alcanzado la costa norte de Cuba.

Mapas que muestran las manchas de Sargassum obtenidas a partir de imágenes de satélite y comunicadas semanalmente a través del Informe experimental sobre la inundación de Sargassum del AOML (enlace)

Perspectivas del sargazo son publicadas una vez al mes por la Universidad del Sur de Florida. Estas perspectivas muestran mapas con las extensiones mensuales (del mes pasado) de Sargassum. La extensión total actual (febrero-marzo de 2023) de Sargazo en los trópicos es similar a los eventos más grandes que ocurrieron en años anteriores (especialmente 2018), con grandes extensiones de Sargassum observadas en el Mar Caribe desde febrero. Si bien este Sargassum permanece en la superficie del mar y se desplaza con ayuda de las corrientes oceánicas, los vientos y las olas, puede crecer y aumentar su densidad, siempre que se encuentre con temperaturas cálidas y abundantes nutrientes. Si la gran cantidad de Sargazo que se encuentra actualmente en el Mar Caribe permanece en la superficie, tiene el potencial de extenderse más ampliamente por todo el Golfo de México y luego por la Corriente en Bucle y la Corriente de Florida (el nombre de la Corriente del Golfo frente a Florida) para alcanzar los Cayos de Florida y la costa este de Florida y las Bahamas.

Lecturas complementarias

Trinanes, J., N.F. Putman, G. Goni, C. Hu y M. Wang. (2023). Monitoring pelagic Sargassum inundation potential for coastal communities. Journal of Operational Oceanography, 16(1):48-59, https://doi.org/10.1080/1755876X.2021.1902682

Andrade-Canto, F., F.J. Beron-Vera, G.J. Goni, D. Karrasch, M.J. Olascoaga, and J. Trinanes Carriers of Sargassum and mechanism for coastal inundation in the Caribbean Sea. (2022). Física de Fluidos, 34(1):016602, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0079055.

Beron-Vera, F.J., M.J. Olascoaga, N.F. Putman, J. Trinanes, G.J. Goni, y R. Lumpkin. (2022). Geografía dinámica y trayectorias de transición del Sargassum en el Atlántico tropical. AIP Advances, 12(10):105107, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0117623.

Trinanes, J., C. Hu, N.F. Putman, M.J. Olascoaga, F.J. Beron-Vera, S. Zhang y G.J. Goni. (2021). An integrated observing effort for Sargassum monitoring and warning in the Caribbean Sea, tropical Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico. Oceanografía 34(4):68-69, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2021.supplement.02.

Miron, P., M.J. Olascoaga, F.J. Beron-Vera, N.F. Putman, J. Trinanes, R. Lumpkin y G.J. Goni. Clustering of marine debris- and Sargassum-like drifters explained by inertial particle dynamics. (2020). Geophysical Research Letters, 47(19):e2020GL089874, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL089874.

Putman, N., R. Lumpkin, M.J. Olascoaga, J. Trinanes y G.J. Goni. (2020). Improving transport predictions of pelagic Sargassum. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 529:151398, https://doi.org/10.1016.j.embe.2020.151398.

Johns, E.M., Lumpkin, R., Putman, N.F., Smith, R.H., Muller-Karger, F.E., Rueda-Roa, D., Hu, C., Wang, M., Brooks, M.T., Gramer, L.J., & Werner, F.E. (2020). El establecimiento de una población pelágica de Sargassum en el Atlántico tropical: Biological consequences of a basin-scale long distance dispersal event. Progress in Oceanography, 182, 102269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2020.102269

Putman, N.F., G.J. Goni, L.J. Gramer, C. Hu, E.M. Johns, J. Trinanes y M. Wang. (2018). Simulación de las vías de transporte de Sargassum pelágico desde el Atlántico ecuatorial hasta el Mar Caribe. Progreso en oceanografía, 165:205-214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2018.06.009.

Encontrar un hábitat adecuado

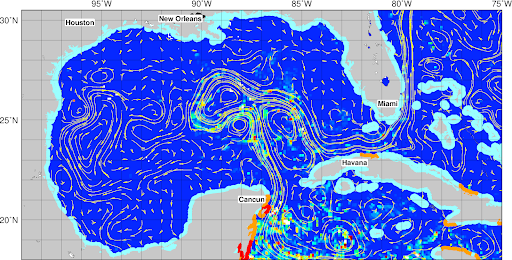

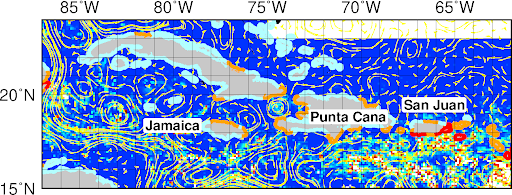

Los entornos físicos preferidos por las larvas del atún rojo del Atlántico dependen de características del Golfo de México como los remolinos. El índice proxy de larvas puede explicar alrededor del 58% de la variabilidad del reclutamiento en función de los cambios en estas características oceánicas, y se utiliza actualmente para guiar los cruceros de investigación interdisciplinarios de la NOAA.

Las condiciones del hábitat adecuado para el atún rojo han cambiado con el tiempo. En esta herramienta, el rojo indica el hábitat adecuado y el azul el inadecuado (demasiado cálido). Los puntos son observaciones de la presencia de larvas de atún rojo. Esta herramienta de datos produce imágenes para descargar como archivos PNG. Para utilizar la herramienta, seleccione una imagen por fecha a continuación. Este índice es utilizado por NOAA Fisheries para guiar las encuestas anuales de muestreo de larvas de atún rojo, y en apoyo de las evaluaciones de las poblaciones de atún rojo.

Mapas en tiempo real y en tiempo diferido

Esta herramienta proporciona acceso a mapas en tiempo real y en tiempo diferido de la distribución de BFT_Index en el Golfo de Mapas a partir de 1993, que se utilizan para rastrear las zonas favorables para la aparición de larvas de atún rojo(Thunnus thynnus, BFT).

El desove del BFT en el Golfo de México se registra durante los meses de primavera del hemisferio norte, y las larvas de BFT se capturan principalmente desde principios de abril hasta finales de mayo. Por ello, el cálculo en tiempo real del BFT_Index se realiza entre el 1 de marzo y el 31 de mayo de cada año.

Período de cálculo del Índice de Aleta Azul en tiempo real: 1 de marzo - 31 de mayo

Fechas disponibles: 03/01/1993 - Primavera actual

Aviso: Los mapas en blanco indican que las condiciones en el Golfo de México son en general desfavorables para la aparición de larvas de BFT.

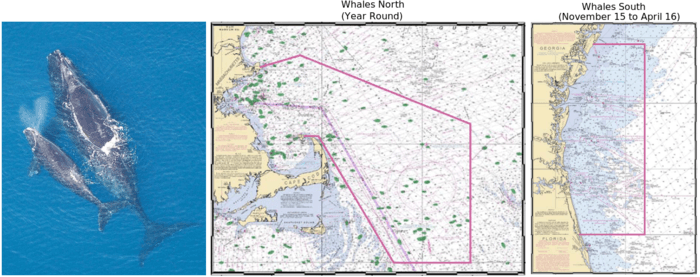

Reducción de la mortalidad de la ballena franca del Atlántico Norte

Las colisiones con barcos (o "choques") son una de las principales fuentes de lesiones y muertes para la ballena franca del Atlántico Norte, que está en peligro crítico de extinción. En un esfuerzo por reducir el número de colisiones con buques, la NOAA Fisheries y la Guardia Costera de Estados Unidos, con el apoyo de la AOML, desarrollaron e implementaron sistemas de notificación obligatoria de buques. Los sistemas fueron aprobados por la Organización Marítima Internacional, una organización especializada de las Naciones Unidas.

El sistema obligatorio de notificación de buques se adoptó formalmente mediante la Resolución A.858(20) de la Organización Marítima Internacional en diciembre de 1998, y se puso en práctica mediante un aviso del Registro Federal de la USCG (66 FR 58066). El sistema comenzó a funcionar el 1 de julio de 1999.

Todos los buques comerciales de 300 toneladas brutas o más están obligados a informar a una estación costera cuando entren en dos zonas de notificación designadas en las que se encuentran ballenas francas, que incluyen: Las aguas de la bahía de Cape Cod, la bahía de Massachusetts, el Gran Canal del Sur y el Santuario Marino Nacional del Banco Stellwagen a lo largo de la costa cercana a la frontera entre Florida y Georgia.

Los buques que informan deben indicar la hora y la ubicación de entrada en el sistema, la velocidad y el destino; ningún otro aspecto de la navegación se ve afectado. A cambio, el barco recibe un mensaje automatizado que proporciona información adicional sobre cómo los navegantes pueden reducir la probabilidad de colisiones con ballenas, incluyendo los lugares de avistamiento reciente de ballenas francas.

La información resumida recopilada a través del sistema obligatorio de notificación de buques incluye los volúmenes de tráfico de buques, las rutas y los puertos de escala, y ayuda a adaptar cualquier medida futura de reducción de las huelgas de buques que sea necesaria.

El Sistema obligatorio de notificación de buques es operado y financiado conjuntamente por la USCG y la NOAA Fisheries, con la asistencia del Laboratorio Oceanográfico y Meteorológico del Atlántico de la NOAA, que proporciona apoyo técnico alojando el motor de software, almacenando y analizando los datos, y generando estadísticas sobre el cumplimiento del Sistema obligatorio de notificación de buques.

El sistema de notificación obligatoria de buques ha recibido y procesado más de 20.000 informes de aproximadamente 4.000 buques comerciales distintos. Todos los buques que informan al sistema de notificación obligatoria de buques reciben un mensaje de respuesta que contiene información sobre cómo evitar colisiones con ballenas, requisitos de límite de velocidad y la ubicación de los últimos avistamientos de ballenas.

Efectos de la corriente de bucle en la pesca

Las simulaciones de los modelos climáticos del Cuarto Informe de Evaluación del Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático (IPCC-AR4) proyectan que la parte superior del océano en el Golfo de México puede aumentar más de 2°C para finales del siglo XXI, y sugieren que el Golfo de México puede convertirse en un hábitat inadecuado para el desove del atún rojo debido a las aguas más cálidas. Sin embargo, dado que los modelos del IPCC-AR4 tienen una resolución muy gruesa (normalmente de unos 100 km), los cambios simulados en los factores importantes para la respuesta de la temperatura del océano superior al cambio climático (la fuerza, la posición y las características de arrastre de la corriente de bucle), están lejos de ser realistas.

Al ampliar estas características en los modelos de alta resolución, los científicos del AOML pueden observar los posibles cambios de hábitat del atún rojo en el futuro. Utilizando esta técnica, nuestros investigadores observan que el aumento de la temperatura de la superficie del mar es mucho menos pronunciado en el norte del Golfo de México, lejos de la costa occidental de Florida. Esto podría deberse a un debilitamiento de la corriente de bucle.

Los científicos del AOML prevén una ralentización del 20-25% de esta corriente (basada en su componente mayor, la Circulación Meridional de Vuelco). Además, el análisis del balance térmico de la capa superficial indica que esto puede tener un efecto de enfriamiento, especialmente en el norte del Golfo de México. El impacto de esto en las pesquerías sería un desplazamiento del hábitat del atún rojo hacia el norte.

Esta investigación indica que la zona de hábitat de desove del atún rojo podría no reducirse tan drásticamente como ha previsto el IPCC-AR4. Los investigadores del AOML seguirán colaborando con el Centro de Ciencias Pesqueras del Sureste de la NOAA para perfeccionar estas proyecciones utilizando datos adicionales y técnicas mejoradas de modelización oceánica.

Estamos a la vanguardia de la investigación y las aplicaciones genómicas.

Ómicas para la economía azul.

La tecnología ómica permite a los investigadores realizar observaciones y análisis que ayudan a las partes interesadas y a los gestores a tomar decisiones en beneficio de sus clientes. Con Omics, podemos:

- Entender el microbioma

- Detectar niveles tróficos superiores

- Mejorar la vigilancia del medio ambiente

Publicación destacada

Publicaciones y referencias

2023

Trinanes, J., N.F. Putman, G. Goni, C. Hu y M. Wang. Monitoring pelagic Sargassum inundation potential for coastal communities. Journal of Operational Oceanography, 16(1):48-59(https://doi.org/10.1080/1755876X.2021.1902682)(2023).2022

Andrade-Canto, F., F.J. Beron-Vera, G.J. Goin, D. Karrasch, M.J. Olascoaga y J. Trinanes. Carriers of Sargassum and mechanism for coastal inundation in the Caribbean Sea. Physics of Fluids, 34(1):016602 (https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0079055) (2022).Kavanaugh, M.T., T. Bell, D. Catlett, M.A. Cimino, S.C. Doney, W. Klajbor, M. Messié, E. Montes, F.E. Muller-Karger, D. Otis, J.A. Santora, I.D. Schroeder, J. Trinanes y D.A. Siegel. La teledetección por satélite y la Red de Observación de la Biodiversidad Marina: Ciencia actual y pasos futuros. Oceanography, 34(2):62-79(https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2021.215)(2021).

Trinanes, J., C. Hu, N.F. Putman, M.J. Olascoaga, F.J. Beron-Vera, S. Zhang y G.J. Goni. An integrated observing effort for Sargassum monitoring and warning in the Caribbean Sea, tropical Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico. 34(4):68-69(https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2021.supplement.02-26)(2021).

2021

Baker-Austin, C., J. TRINANES, y J. Martinez-Urtaza. Las nuevas herramientas que revolucionan la ciencia de Vibrio. Microbiología ambiental, 22(10):4096-4100 (https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920-15083) (2020).Jiang, L.-Q., R.A. Feely, R . Wanninkhof, D. Greeley, L. Barbero, S. Alin, B.R. Carter, D. Pierrot, C. Featherstone, J. HOOPER, C. Melrose, N. Monacci, J.D. Sharp, S. Shellito, Y.-Y Xu, A. Kozyr, R.H. Byrne, W.-J. Cai, J. Cross, G.C. Johnson, B. Hales, C. Langdon, J. Mathis, J. Salisbury y D.W. Townsend. Coastal Ocean Data Analysis Product in North America (CODAP-NA)-An internally consistent data product for discrete inorganic carbon, oxygen, and nutrients on the North American ocean margins. Earth System Science Data, 13(6):2777-2799(https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-2777-2021)(2021).

Kearney, K.A., S.J. Bograd, E. Drenkard, F.A. GOMEZ, M. Haltuch, A.J. Hermann, M.G. Jacox, I.C. Kaplan, S. Koenigstein, J.Y. Luo, M. Masi, B. Muhling, M. Pozo Buil y P.A. Woodworth-Jefcoats. Using global scale earth-system models for regional fisheries applications. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8:622206(https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.622206)(2021).

Miron, P., M.J. Olascoaga, F.J. Beron-Vera, N.F. Putman, J. TRINANES, R. LUMPKIN y G.J. GONI. Clustering of marine debris- and Sargassum-like drifters explained by inertial particle dynamics. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(19):e2020GL089874(https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL089874)(2020).

Trinanes, J., y J. Martínez-Urtaza. Escenarios futuros de riesgo de infecciones por Vibrio en un planeta que se calienta: Un estudio cartográfico global. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(7):E426-E435(https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00169-8) (2021).

Valle-Levinson, A., V.H. Kourafalou, R.H. Smith e Y. Androulidakis. Estructuras de flujo sobre ecosistemas coralinos mesofóticos en el este del Golfo de México. Continental Shelf Research, 207:104219(https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2020.104219)(2020).

2020

Androulidakis, Y., V. Kourafalou, L.R. Hole, M. LE HENAFF y H.-S. Kang. Pathway of oil spills from potential offshore Cuban exploration: Influencia de la circulación oceánica. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 8(7):535 (https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8070535) (2020).Frys, C., A. Saint-Amand, M. LE HÉNAFF, J. Figueiredo, A. Kuba, B. Walker, J. Lambrechts, V. Vallaeys, D. Vincent y E. Hanert. Fine-scale coral connectivity pathways in the Florida Reef Tract: Implications for conservation and restoration. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7:312(https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00312)(2020).

JOHNS, E.M., R. LUMPKIN, N.F. Putman, R.H. SMITH, F.E. Muller-Karger, D. Rueda-Roa, C. Hu, M. Wang, M.T. Brooks, L.J. Gramer y F.E. Werner. El establecimiento de una población pelágica de Sargassum en el Atlántico tropical: Biological consequences of a basin-scale long distance dispersal event. Progress in Oceanography, 182:102269(https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2020.102269)(2020).

LE HÉNAFF, M., F.E. Muller-Karger, V.H. Kourafalou, D. Otis, K.A. Johnson, L. McEachron y H.-S. Kang. Evento de mortalidad de corales en los bancos Flower Garden del Golfo de México en julio de 2016: ¿Hipoxia local debida al transporte a través de la plataforma de aguas de inundaciones costeras? Continental Shelf Research, 190:103988(https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2019.103988)(2019).

Putman, N., R. LUMPKIN, M.J. Olascoaga, J. TRINANES y G.J. GONI. Improving transport predictions of pelagic Sargassum. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 529:151398(https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2020.151398)(2020).

Wanninkhof, R., J. TRINANES, G.-H. Park, D. Gledhill y A. Olsen. Large decadal changes in air-sea CO fluxes in the Caribbean Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans, 124(10):6960-6982(https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JC015366)(2019).

Wanninkhof, R., D. Pierrot, K. Sullivan, L. Barbero y J. TRINANES. A 17-year dataset of surface water fugacity of CO2 along with calculated pH, aragonite saturation state, and air-sea CO2 fluxes in the northern Caribbean Sea. Earth System Science Data,12(3):1489-1509(https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-1489-2020)(2020).

2018

Putman, N.F., Goni, G., Gramer, L., Hu, C., Johns, E., Trinanes, J. y Wang, M., 2018: Simulación de las vías de transporte de Sargassum pelágico desde el Atlántico Ecuatorial hacia el Mar Caribe. Progress in Oceanography, 165:205-214(doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2018.06.009).2017

Muhling, B. A., R. Brill, J. T. Lamkin, M. A. Roffer, S.-K. Lee, Y. Liu, y F. Muller-Karger, 2017: Proyecciones del uso futuro del hábitat por el atún rojo del Atlántico: modelos de distribución mecanicistas frente a correlativos. ICES. J. Marine Science, 74(3):698-716 (doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsw215).Carrillo,L., J.T. Lamkin, E.M. Johns, L. Vasquez-Yeomans, F. Sosa-Cordero, E. Malca, R.H.Smith, y T. Gerard, 2017: Vinculación de los procesos oceanográficos y los recursos marinos en la subárea del Gran Ecosistema Marino del Mar Caribe occidental. Elsevier, Environmental Development, 22:84-96(doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2017.01.004).

2016

Domingues, R., G. Goni, F. Bringas, B. Muhling, D. Lindo-Atichati y J. Walter (2016). Variabilidad de las condiciones ambientales preferidas por las larvas de atún rojo del Atlántico (Thunnus thynnus) en el Golfo de México durante 1993-2011. Oceanografía pesquera, 25(3): 320-336.Carrillo, L., E. M. Johns, R. H. Smith y J.T. Lamkin, 2016: Vías e hidrografía en el Sistema Arrecifal Mesoamericano, Parte 2: Estructura termohalina. Cont. Shelf Res., 120, 41-58,(doi:10.1016/j.csr.2016.03.014).

Lee, T.N., N. Melo, N. Smith, E.M. Johns, C.R. Kelble, R.H. Smith y P.B. Ortner, 2016: Circulación y renovación del agua de la Bahía de Florida. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 92(2):153-180,(doi:10.5343/bms.2015.1019).

2015

Karnauskas, M., M.J. Schirripa, J.K. Craig, G.S. Cook, C.R. Kelble, J.J. Agar, B.A. Black, D.B. Enfield, D. Lindo-Atichati, B.A. Muhling, K.M. Purcell, P.M. Richards y C. Wang, 2015: Evidencia de la reorganización del ecosistema impulsada por el clima en el Golfo de México. Global Change Biology, 21(7):2554-2568, (doi:10.1111/gcb.12894).Muller-Karger, F.E., J.P. Smith, S. Werner, R. Chen, M. Roffer, Y. Liu, B. Muhling, D. Lindo-Atichati, J. Lamkin, S. Cerdeira-Estrada, y D.B. Enfield, 2015: Variabilidad natural de las condiciones oceanográficas superficiales en la costa del Golfo de México. Prog. in Oceanogr., 134:54-76, (doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2014.12.007.)

Muhling, B.A., Y. Liu, S.-K. Lee, J.T. Lamkin, M.A. Roffer, F. Muller-Karger, y J.W. Walter, 2015: Potential impact of climate change on the Intra-Americas Seas: Part 2: Implications for Atlantic bluefin tuna and skipjack tuna adult and larval habitats. J. Mar. Syst., 148:1-13,(doi:10.1016/j.marsys.2015.01.010).

Carrillo, L., E. M. Johns, R. H. Smith, J. T. Lamkin y J. L. Largier, 2015: Vías e hidrografía en el Sistema Arrecifal Mesoamericano Parte 1: Circulación. Continental Shelf Research, 109:164-176,(doi:10.1016/j.csr.2015.09.014).

2012

Lindo-Atichati, D., Bringas, F., Goni, G., Muhling, B., Muller-Karger, F.E. y Habtes, S. (2012) La variación de las estructuras de mesoescala influye en la distribución de las larvas de peces en el norte del Golfo de México. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 463:245-257.Lindo-Atichati, D.,F. Bringas, G.J. Goni, B. Muhling, F.E. Muller-Karger y S. Habtes, 2012: La variación de las estructuras de mesoescala influye en la distribución de las larvas de peces en el norte del Golfo de México. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Series, 463:245-257, doi:10.3354/meps09860.

2011

Muhling, Barbara A., J. T. Lamkin, J. M. Quattro, R. H. Smith, M. A. Roberts, M. A. Roffer y K. Ramírez, 2011: Recogida de larvas de atún rojo (Thunnus thynnus) fuera de las zonas de desove documentadas del Atlántico occidental. Bull. Mar. Sci., 87(3):687-694.Muhling, B. A., S.-K. Lee, J. T. Lamkin, y Y. Liu, 2011: Predicción de los efectos del cambio climático en el hábitat de desove del atún rojo (Thunnus thynnus) en el Golfo de México. CIEM. J. Mar. Sci., 68(6):1051-1062, doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsr008.

2010

Muhling, B.A., Lamkin, J.T. y Roffer, M.A. (2010) Predicción de la presencia de peces de atún rojo del Atlántico (Thunnus thynnus). Oceanogr.Preferred environmental conditions for Atlantic bluefin tuna larvae in the northern Gulf of Mexico: building a classification model from archival data. Fish Oceanogr. 2(19):526-539.

¿Buscando literatura? Busque en nuestra base de datos de publicaciones.